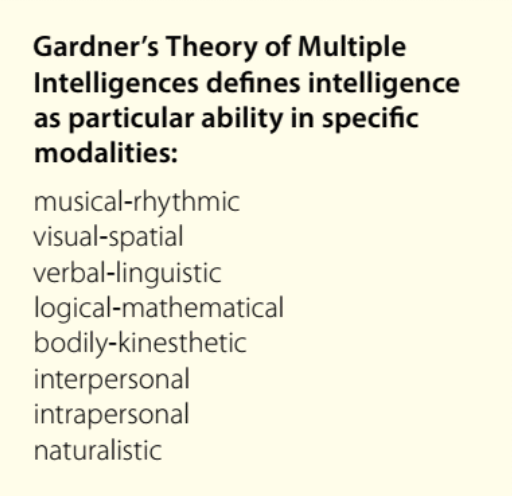

Providing for multiple intelligences in a classroom can be an extraordinary endeavour. A lesson for twenty students may require forty different teaching strategies to be considered truly best practice. Howard Gardner explains that “all individuals harbour numerous internal representations in their minds,” referring to the eight multiple intelligences which are organized in a structure with hierarchical and systematic implications. One student considered a “musical” learner may grasp multiplication best by singing notes descending in scale as number facts become larger. That same student, however, may become lost in a song about states of matter because when it comes to physics, her mind prefers to “speak ” in a bodily-kinesthetic “intellectual language” (Gardner 70) when negotiating such concepts, so she needs to run around impersonating a molecule in a liquid, and slow to a crawl as she “freezes” into a solid. There is certainly no adequate one-size-fits-all pedagogical approach to any lesson, and there may not even be a one-size-fits-one. “If one wants to educate for genuine understanding, then, it is important to identify these early representations, appreciate their power, and confront them directly and repeatedly” (Gardner 71). Classroom filmmaking is a practical, user-friendly approach to incorporating all multiple intelligences within the parameters of a single project. The filming experience offers opportunities for students to accommodate the diversity of their cognitive capacities through various roles and responsibilities.

Students may be assigned parts that cater to their preferred mental processors, or teachers might allow students to select their own duties, perhaps revealing their true dominant intelligences naturally. Supported by pedagogical theory and exemplary of experiential learning, classroom filmmaking is an engaging and effective venture where all students are included and inspired to achieve their highest potentials.

Students may be assigned parts that cater to their preferred mental processors, or teachers might allow students to select their own duties, perhaps revealing their true dominant intelligences naturally. Supported by pedagogical theory and exemplary of experiential learning, classroom filmmaking is an engaging and effective venture where all students are included and inspired to achieve their highest potentials.

The Script and Storyboard (Plotting and Pre-production)

When planning a film, the teacher may guide students toward a general topic if there is a specific learning goal, such as prepositional phrases, Canadian history or texturing with coloured pencils, or, if the intention is to experience film-making for its differentiating benefits, students may brainstorm topics from a clean slate. Initial brainstorming may begin as a solitary endeavour where students explore their own interests first before compiling a comprehensive list of film concepts collaboratively during a whole class discussion. This progression from intrapersonal exploration to interpersonal conference generates the widest variety of ideas, offering students a more enriched accumulation of concepts to consider before democratically deciding which direction the film will take.

Once the general direction has been defined, the teacher might write the script, or the task can be set for linguistic students eager to try their pens at screenwriting. The script itself may be as simple or complex as students prefer, including only dialogue and action or incorporating more specialized features such as script notes and shots. A common format includes character names centred in capital letters, dialogue left-aligned beneath them, and action centred in parentheses. Students might also want to research how to format a screenplay online, as there are many layouts acknowledged.

After a script has been finalized, spatial storyboard artists create an additional document that fleshes out the script in the form of sketches, much like a comic strip. Storyboard artists sketch each scene as it would look on the screen, including all characters, props and background. The storyboard helps the cast and crew visualize the film and bridge the paper script to the final motion picture.

Location scouts can now begin searching the school property and other local environments for potential sets. This consideration is not only based on aesthetics, but also logistics of transportation, safety and privacy of cast, crew and the public, and whether parent permission is required for travel. Naturalists can help consider aspects of nature, sunlight and weather.

The Stars (Subjects)

Although social students tend to be in their element performing in front of a camera, the demands of different roles may reach out to different intelligences, so it’s important for students and teachers to know the script, the story and the specific roles. A key speaker in a film may be best for an oral linguist. A song may call for musical performers, while action or improvisational scenes may entice bodily-kinesthetic students. Close-up, sentimental shots may require the meditative talent of an intrapersonal actor who can portray his or her exceptional self-awareness in an emotional facial expression.

The Shot (Cinematography)

The same spatial artists who designed the storyboards can now change their tools from pens to the lens and bring to life their sketched visions. As spatial artists tend to see the big picture, their choices of shot types may come naturally and without explanation, especially if they appreciate the theme and purpose of the film. When establishing setting or atmosphere, they may choose extreme wide shots or cutaways (shots of additional components of a scene beside the main subject) to satisfy their vision of the world they’re creating. This includes choices between high and low angle shots, differentiating between the perception of a subject’s power or insignificance.

Unfortunately, classroom filmmaking does not receive the same budget as film projects out of Holly/Bollywood. This limits the purchase of pieces of equipment that play essential roles in producing a quality film, such as jibs or dollies. But this doesn’t mean a classroom film must look completely amateur. Students who are highly bodily-kinesthetic may enjoy becoming the equipment themselves. Fundamental camera conduct requires a student who is in control of his or her muscles—to keep the camera steady at all times so the audience is unaware of its existence. This is no easy physical feat, and it becomes more of a test of acrobatics when the scene calls for action or movement. A follow shot (trailing a subject) might put the camera operator on roller blades or a bicycle. For shots requiring tracking (movement left and right) or dollying (movement forward and backward), one student might hold the camera while sitting in a rolling chair while another student pushes it. An arc shot might have a student shooting out the passenger window of a moving car. Creativity and physical aptitude have the potential to maintain high quality of a class-room film.

The Slow-Down (Editing)

The editing process begins with uploading all clips to a video editing program. I suggest using the video editing program WeVideo for classroom filmmaking because of its flexible online accessibility and its collaborative capabilities. WeVideo has agreed to offer Canadian Teacher Magazine readers access to an exclusive two-month trial of their program. Interested educators may contact the author, Matthew Baganz, for more information about the free trial.

The next step requires a minimum of arranging the clips in an order that tells the story best. A professional-looking film will include many elements in addition to clips, such as transitions, audio, graphics and text, and may be quite a puzzle to piece together. A logical-mathematical thinker may enjoy taking on this challenge, coherently sequencing elements of the story, syncing action and transitions with audio and music tracks, and layering special effects such as frames and overlays. Naturally the musically-inclined will play a vital role in selecting and managing the sound track.

The Show (Presentation)

The nature of filmmaking implies an eventual audience. Perhaps the final film will debut at an assembly, a graduation or a cultural fair. For all live presentations, it is natural to give the film an introduction. Interpersonal hosts or linguistic speakers may revel in taking centre stage to present their hard work.

The Study (Reflection)

Reflection is a significant component of any learning experience. Circling back to the initial brainstorming stage, the conclusion is at first an intrapersonal reflection of the project and its learning goals. Students may now consider how their comprehension of the film’s topic developed after exploring it through the lens of a storyboard or a special effect. Hopefully, the class project adds dimension and a deeper understanding of the learning goals and the filmmaking experience itself. After all, film captures and preserves moments in time—a convenient opportunity for students to reflect on the stages of the filmmaking process over and over again, both intrapersonally and interpersonally, to both celebrate and grow from them.

References

A., Jonathan, and Megan Diane. “Crew Jobs: Every Film Crew Position and Job Description.”Project Casting. Project Casting Inc., 30 Nov. 2014. Web. 15 July 2016. projectcasting.com/tips-and-advice/crew-jobs-every-film-crew-position-job-description.

Gardner, Howard, and Shirley Veenema. “Multimedia and Multiple Intelligences.” Multimedia and Multiple Intelligences(1999): 69-75. Print.

“Getting Started In Filmmaking.”Getting Started in Wildlife Filmmaking: Film Guide. Ed. Rob Nelson. The Wild Classroom, n.d. Web. 15 July 2016. thewildclassroom.com/wildfilmschool/gettingstarted/.

“Media College – Video, Audio and Multimedia Resources.”Media College – Video, Audio and Multimedia Resources. Ed. Dave Owen. Wavelength Media, n.d. Web. 15 July 2016. mediacollege.com/.

“Multiple Intelligences Oasis – Howard Gardner’s Official MI Site.” Multiple Intelligences Oasis. Ed. Victoria Nichols. BlueLuna, n.d. Web. 15 July 2016. multipleintelligencesoasis.org/.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Matthew Baganz

Matthew Baganz holds a Master’s degree in Multicultural Education and is the PYP 5 Classroom Teacher and PYP Maths Coordinator at Strothoff International School in Dreieich, Germany. He can be reached at matthewbaganz@gmail.com.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Jan/Feb 2017 issue.