Where will you be in seven years? Teaching? Travelling? In Canada? Abroad? Whatever you do, avoid Point Nemo in the Pacific Ocean. NASA aims to “de-orbit” the International Space Station (ISS) and have it crash there. This was planned for 2024, but is now set for January, 2031.

Point Nemo floats 2,688 kilometres away from any land. Antarctica lies to the south. Pitcairn Islands to the north. New Zealand to the west. Easter Islands to the east. It has actually been a spacecraft cemetery since the 1970s.

Point Nemo floats 2,688 kilometres away from any land. Antarctica lies to the south. Pitcairn Islands to the north. New Zealand to the west. Easter Islands to the east. It has actually been a spacecraft cemetery since the 1970s.

Failing or decommissioned satellites and spacecraft can either be sent further into space or brought out of low-Earth orbits to crash at Point Nemo. Most objects burn up with the friction and heat of atmospheric re-entry. Large pieces of debris that don’t could devastate sensitive or inhabited parts of our planet. 2031 will be our biggest test.

What has already fallen?

In 1979, NASA’s first space station, Skylab, had an uncontrolled re-entry. Mission Control had no way to steer the 77-ton space station as it plunged to Earth. Burning fragments of it hit the Indian Ocean and parts of Western Australia.

In 2001, Russia de-orbited their 142-ton Mir space station. Most fragments fell into the Pacific Ocean, although some did hit Fiji. China’s space stations, Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2, had uncontrolled re-entries in 2018 and 2019 but mostly burned up and fell over the South Pacific. Many countries have had failed rockets re-enter the atmosphere and scatter fragments over the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

At the start of 2024, Astrobotic’s commercial Peregrine Mission One (headed to the moon) lost propulsion and also crashed into the Pacific. In the last five decades, over 260 spacecraft have crash-landed near Point Nemo (48°52.6’ S latitude, 123°23.6’ W longitude).

This watery graveyard now contains bits of space cargo ships, space stations, old spy satellites, NASA’s Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (decommissioned in 2000), spent oxygen and fuel tanks, and weather satellite debris. The main goals are always to avoid collisions and damage to human populations. Ecological concerns exist as well, but around Point Nemo, there is very little sea life.

How is the ISS different?

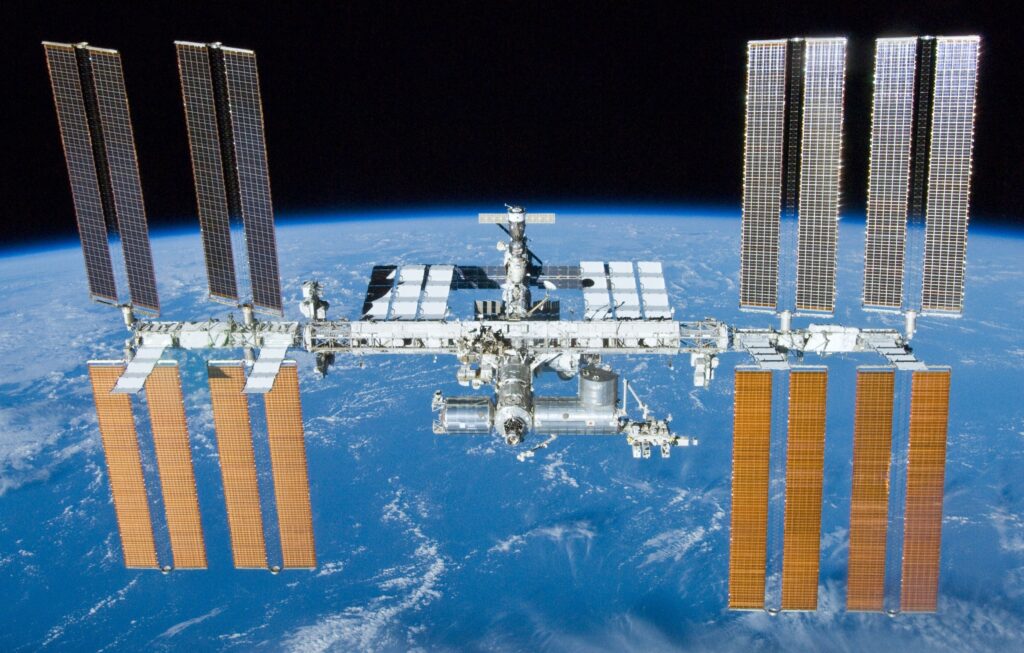

Despite the myriad space machinery sent up and brought down, the International Space Station remains unique. It’s the size of a football field and three times the size of the Mir space station. It orbits our planet at 29,000 km/hr. It has cost over $150 billion to build and maintain and would weigh 460 tons back on Earth.

Designed to function as an international science laboratory in low-Earth orbit, the ISS has been continuously crewed since 2000. It has hosted over 250 astronauts from 20 different countries. Every 90 minutes, it orbits our planet, observing 16 sunrises and sunsets a day! It’s the largest space structure ever made and will be the biggest de-orbiting project in human history.

Construction began in 1998, with the Russian-built Zarya module. NASA, the European Space Agency, Russia’s Roscosmos Space Program, the Canadian Space Agency, and Japan’s Aerospace Agency were the five collaborators. After 42 separate launches, the ISS now boasts 16 connected modules and a vast network of solar panels. These were all assembled out in space, thanks to remote-controlled Canadarm technology. In fact, seven different Canadian astronauts have lived and worked on board.

Initially, the famous space station was to be retired in 2024. Plans to continue conducting research and to use the lab to support deep-space exploration extended that through 2030. What work do they do? ISS scientists investigate new states of matter, astrophysics, diseases, and growing foods in space, and study the effects of space travel on machines, humans, and other organisms.

The ISS also allows for international collaboration on an unprecedented level. Unfortunately, as politics and economics on Earth strain and sever some of those relationships, the dream of the ISS is faltering. As of 2024, for example, Russia will no longer participate in its work, budgeting, or de-orbiting.

What is the crash plan?

As 2031 approaches, NASA and its partners will salvage what equipment and modules they can and then lower the operational altitude of the space station. Cargo space vehicles will be sent up to push the decommissioned ISS out of orbit. As it re-enters Earth’s atmosphere, they expect much of it to burn up. Pieces that do not should crash into the remote South Pacific at Point Nemo.

Before the ISS ends its life, some surprising players plan to study and interact with it. Elon Musk, founder and CEO of SpaceX, is the most-known individual inspired by and working with the ISS. Another famous figure is movie star Tom Cruise, who daringly plans to fly up to it to film a movie in 2025 (floating outside it, perhaps repairing it, depending on the storyline). In 2020, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine tweeted that working with Cruise “could help to inspire a new generation of engineers to make NASA’s ambitious plans a reality.”

What is the new reality?

NASA’s Artemis program will return to the moon and then further explore deep space. Companies like SpaceX, Starlink, and OneWeb will deploy “mega-constellations” of satellites to provide better global Internet coverage. Other space-focused companies plan to mine resources on asteroids and the moon, or manufacture metal alloys and semiconductors, for example, out in microgravity.

Space tourism is also on the horizon. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic are actively developing suborbital space tours to allow (very wealthy) clients to experience rocket flights, weightlessness, and incredible views of Earth from space. The exploration of space, space travel, and scientific experimentation are now the domain of private industry. Get used to the names SpaceX, Northrop Grumman, Axiom Space, Rocket Lab, Blue Origin, and Canada’s MDA and Magellan Aerospace. Government space programs must partner with for-profit companies to handle the astronomical costs.

NASA already has a Commercial Spaceflight Division headquartered in Washington, D.C. It is Voyageur Space and Airbus who plan to build and operate the fixed module Starlab for future ESA-NASA experiments.

Soon enough, that famous “final frontier” will be speckled with space hotels and interplanetary mining companies. But if we do build new stations on the Moon and eventually reach and settle humans on Mars, it will certainly be thanks to the international cooperation, experimentation, and inventions from decades of astronauts manning the International Space Station.

The ISS in our classrooms

The ISS offers huge potential for lessons and conversations in our schools and around the world. Science, Technology, and Social Studies courses can examine different components, orbits, experiments, and the route to Point Nemo. Language classes could create science fiction stories or dystopian poetry of the final days on the ISS, its fiery tumble back to Earth, or provocative ads for future space industries. Phys Ed classes could simulate astronaut training exercises.

Around the globe, education has been inspired and improved by the assembly, function, and innovations of the International Space Station. It united nations and accelerated technologies. It expanded our vision and plans for the future. It will do so for seven years more. However, come January 2031, make travel plans with care. Look skyward to glimpse a burning spectacle (several kilometres wide) as the remnants of the ISS come crashing down, headed for Point Nemo in the Pacific Ocean.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maria Campbell

Maria Campbell, OCT, is a career teacher with the Ottawa Catholic School Board, currently at Lester B. Pearson High School. She has also lived and worked abroad, does rigorous research for nonfiction articles, and writes fiction and poetry (on top of marking all her student projects). She firmly believes that relating disparate fields and issues makes for stimulating lessons and conversations in and out of the classroom. Publications like Canadian Teacher Magazine spark and promote that too.

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Spring 2024 issue.