Ontario teachers take time out of their careers to “worldschool” their daughters. The upshot?

Lloyd and I met at Nipissing University’s Faculty of Education during a pick-up game of basketball. When our relationship turned serious, we decided to get married and head abroad to teach ESL. Back then, in the ancient times before the Internet, applying for overseas positions was a matter of finding the right job at the right time. To wit, I spotted this ad in the Globe and Mail: International Teaching Jobs – send a SASE to Nowheresville, New Brunswick.

Lloyd and I met at Nipissing University’s Faculty of Education during a pick-up game of basketball. When our relationship turned serious, we decided to get married and head abroad to teach ESL. Back then, in the ancient times before the Internet, applying for overseas positions was a matter of finding the right job at the right time. To wit, I spotted this ad in the Globe and Mail: International Teaching Jobs – send a SASE to Nowheresville, New Brunswick.

When we received our first package, we knew we had hit the mother lode. Cobbled together on a sheet of paper were hundreds of ads from around the world looking for ESL instructors. A language school in South Korea processed our work visas, and we were in the air before the ink on our marriage certificate was dry. Thus began our life as a travelling partnership, a practice that continued even after the children arrived.

Domestic life set in after we returned to Canada. By all appearances, we were the typical Canadian family, but in fact, we were bored, burned out, and struggling financially, having racked up $18,000 on our credit card. We needed a “life re-set,” so ten years after the honeymoon and two kids later, we decided to dust off our backpacks and head out. This time we sold every single possession down to the last grain of salt to wipe out the debt and finance a two-year stint in Costa Rica.

We organized the trip to directly expose our daughters to biology, social studies, geography, history, and international relations. All we had to do was deposit the girls at the location and let their day-to-day surroundings perform the incidental instruction. Without so much as a lesson plan, for example, the girls would learn a foreign language. The larger goal was values-based. Lloyd felt we were only paying lip service to environmentalism while driving two cars around.

We decided to live like the locals in Costa Rica, taking public transportation, and living on a limited income, to truly understand what it was like to live in the developing world.

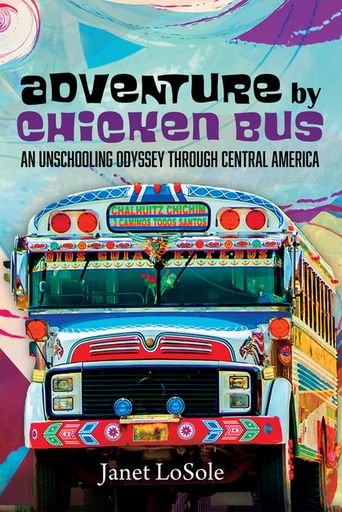

We touched down at the tail end of turtle nesting season and then travelled by chicken bus to the sleepy island backwater of Parismina, on the Caribbean side of Costa Rica. (Chicken Bus: a colloquial term used to describe the run-down, discarded school buses from North America sold to Latin American countries, where they are used for public transportation.)

Canoeing in canals.

We registered for late-night beach patrols, organized to deter illegal poachers from decimating the endangered sea turtle population. Further north, in the canals of Tortuguero National Park, we catalogued dozens of Costa Rica’s famous wildlife from the comfort of a canoe.

When we visited a non-profit organization that arranged stays in the Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve with a BriBri family, I was consumed with fear about the girls’ safety, so I made them wear rubber boots the entire time we were in the jungle.

Tales of piracy, pillaging, and infernos enticed me to convince Lloyd to trek all the way to Panama City since we had to leave Costa Rica anyway to renew our tourist visas. The journey was excruciating, plowing over mountainous roads in a small van. We chopped up the route by visiting a city called David—a discount shoppers’ heaven—where I was reduced to buying myself men’s underwear.

At the Panama Canal’s Miraflores Locks, the girls went berserk racing around the museum. When the staff announced that vessels were passing through the locks, we rushed out to the bleachers. A container ship called China Shipping was transiting at a snail’s pace, and one eyeball could scarcely take in the sight of the leviathan at one glance.

That night, we received an email from a school in Costa Rica interested in interviewing Lloyd for a teaching position, so we bundled up our belongings and headed back.

Lloyd was offered the teaching position at the interview, so we settled into a village to live like the locals. Eventually, some folks heard that not only was I a teacher, but a qualified ESL instructor! They asked me to please teach them English, as it meant broader employment opportunities. I pitched the idea to the local high school, and got permission to use the building to hold classes.

At first, we tackled the basics, such as personal introductions. Eduardo, who owned a video store, rose from his desk.

“Hello, mya name ees Eduardo, Ima esstudent.”

I corrected him. “I’m a student.”

He nodded. “Ima esstudent.”

“I’m. A. Student.”

“Sí, Ima esstudent.”

I puzzled for a bit then wrote on the board: I’m student. “Please say this.”

Ok. I’m esstudent.”

Perfect!

The girls often helped out, babysitting toddlers in the hallway (a common occurrence in this family-friendly culture) while I yammered away in the poorly lit classroom.

After one year in the village, we left Costa Rica for good and headed off on a multi-month return to Canada.

Nicaragua was charming, but despite the museums, galleries, and concerts, we faced deteriorating infrastructure daily, using flashlights during power outages and flushing and washing with water collected in garbage pails. Young boys approached us begging for money. Jocelyn and Natalie were too young to know how to support people of the developing world effectively, so we explained the importance of shopping only at local businesses.

La Miliciana

By the time we arrived in Estelí, the girls had seen, everywhere, an iconic image of the Contra War: a woman breastfeeding her baby with a rifle slung over her shoulder. A discussion about casualties had a devastating impact after Jocelyn learned that children died during the conflict.

Passing through Honduras, one of the most dangerous countries in the world outside a war zone was a nail-biter, but more terrifying was crossing the Bay of Omoa by boat to Dangriga, Belize. Once there, I figured that a pit stop to a hot sauce factory could be educational, too, right?

Bienvenidos a Honduras

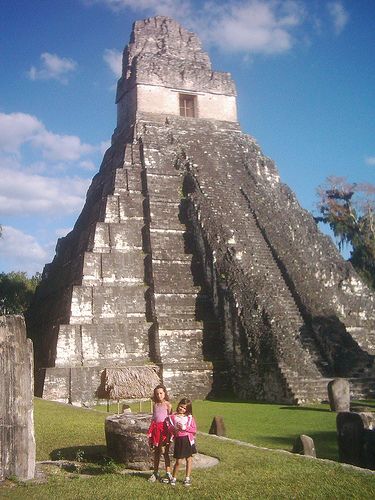

Studying the history of the Mayan world included touring Tikal National Park in Guatemala, and afterwards the outstanding Museum of Mayan Civilization in Chetumal, Mexico. The region stretching from southeastern Mexico to the middle of Honduras is rife with ruins, many of them concealed under a mound of earth.

With one eye on the bank account and the other on the forecast, we finally returned home, broke and suntanned nearly two years later. We felt victorious, having hiked the rainforests, kayaked on the Pacific, ziplined over the jungle, and rescued endangered sea turtles. Most importantly, the girls were exposed to the environmental and economic realities faced by those in the developing world.

Tikal

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Janet LoSole

Janet LoSole began travelling the world as a teen. She earned a Bachelor of Education degree in 1992 from Nipissing University and later, TESOL certification. Family life was no deterrent to roaming the world. As soon as her daughters were old enough, she and husband embarked on an adventure to Central America. Janet recounts their experiences in Adventure by Chicken Bus: An Unschooling Odyssey through Central America. She is currently an online ESL instructor with Open English.

Her writing can be found on her website: https://www.adventurebychickenbus.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JanetLoSole

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/janetlosole/?hl=en

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Spring 2021 issue.