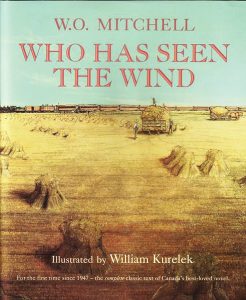

While cicadas are making loud noises outside under the hot sun, I stay inside and read quietly. My summer read is W.O. Mitchell’s first novel, Who Has Seen the Wind, a classic of Canadian literature. First published in 1947, the book tells an ageless story of Brian O’Connal’s childhood in a small Saskatchewan prairie town. The town was so small that there was only one doctor, Peter Svarich. Folks in the town wore multiple hats: Mr. Neally was the mayor and also owner of the town’s two-chair barber shop; Jake Harris, the town garbage-, fire- and police-man, owned a hardware store; Judge Montimer, district agent for the MacDougall Implement Company and police magistrate for the district, was also a member of the school board; Mr. Thorborn was the owner of a livery stable and dray business and also chairman of the school board. A life was modest there and then. James Digby, principal of the town’s public school, earned just fourteen hundred a year and lived alone in his boarding-house room. He owned one pair of shoes and had a hole in his sock!

While cicadas are making loud noises outside under the hot sun, I stay inside and read quietly. My summer read is W.O. Mitchell’s first novel, Who Has Seen the Wind, a classic of Canadian literature. First published in 1947, the book tells an ageless story of Brian O’Connal’s childhood in a small Saskatchewan prairie town. The town was so small that there was only one doctor, Peter Svarich. Folks in the town wore multiple hats: Mr. Neally was the mayor and also owner of the town’s two-chair barber shop; Jake Harris, the town garbage-, fire- and police-man, owned a hardware store; Judge Montimer, district agent for the MacDougall Implement Company and police magistrate for the district, was also a member of the school board; Mr. Thorborn was the owner of a livery stable and dray business and also chairman of the school board. A life was modest there and then. James Digby, principal of the town’s public school, earned just fourteen hundred a year and lived alone in his boarding-house room. He owned one pair of shoes and had a hole in his sock!

Seven decades have passed since Mitchell created Brian’s story. Of course, things are a lot different now: youngsters spend most of their waking hours inside in front of computer screens instead of going outside to play. Teachers are much more dignified (they go to their cottages during the summer holiday). So are pupils. No physical, sexual, verbal and psychological abuse is allowed in school. Strapping is history. But some things have not changed over the years: parental love, children’s curiosity, bullying, racism, poverty, just to name a few.

In Who Has Seen the Wind, 6-year-old Brian didn’t wash his hands one morning and lied about it. His grade one teacher, Miss MacDonald, made the little boy stand in front of the classroom and hold up his unclean hands for the thirty pairs of eyes to see. She threatened him with God’s punishment. The boy eventually collapsed. Later, his mother, Maggie O’Connal, had a parent-teacher interview with Miss MacDonald. She said to her, “I have few friends or acquaintances—instead—I have my husband and two sons. Brian is mine. I bore him. In doing so I got hurt—slightly. Since the first nine months, he has been outside me, and I suppose I have regretted that ever since. It’s much easier to protect them when they are inside your womb, Miss MacDonald. Perhaps if you were to have a child in yours for about two months, you might be a happier and a better teacher.” A mother’s love and devotion for her children is obvious. And during the interview Mrs. O’Connal asked Miss MacDonald an important question, “Do you like children?” The mother continued, “To be a teacher—a person should. I think it would help a lot.” I once asked a principal of a middle school in Toronto what qualities a good teacher possesses. To him, love of children was one of them.

Children are curious by nature because everything is new to them. There are so many firsts. Naturally they wonder a lot. They ask tons of questions and search for answers. After Brian and his friend, Forbsie Hoffman, first saw baby pigeons in the nest, he asked his father how the baby pigeons got in the eggs in the first place. “The father pigeon put them there,” Brian’s father replied. “How?” the inquisitive son continued to ask. After the two boys watched the births of baby rabbits, Brian asked his father how rabbits got started. “The father rabbit plants the seeds,” Brian’s father told his thoughtful son. Children’s curiosity makes them a natural learner. It helps both parents and teachers find countless teachable moments.

Being bullied is a common childhood experience. Even powerful people like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton were bullied when they were young. Girls’ words can be just as hurtful as boys’ fists. Once when I worked at an elementary school in Toronto, I overheard an Asian girl say to her classmate, a black girl, “You are so ugly. You should have an operation like Michael Jackson.” I stepped in and said to the black girl, “You are beautiful. You don’t need any operation.” In Who Has Seen the Wind, the Chinese sister and brother, Tong and Vooie Wong, had suffered from emotional bullying at the hands of their classmate, 10-year-old Mariel Abercrombie. Mariel started another whispering campaign against the Wongs after Tong informed the class that her mother had been bought by her father for a lot of money. Isolation followed at recess. On Tong’s birthday, Mariel made a riddle about Tong: “She’s in Grade Four. She has black hair that isn’t curly. It is straight and it is stringy and kind of greasy! She is yellow and has slanty eyes!” Even though Tong invited girls in her class to her birthday party at her family’s Bluebird Café, nobody showed up except her teacher, Ruth Thompson, who brought the birthday girl a present and card.

After I read Who Has Seen the Wind, I thought we need teachers like Miss Thompson, Brian’s new teacher, who called her pupils “my children” and deeply cared about them. When the siblings, Tong and Vooie, were not doing very well in school, she sent them to see the doctor and then she went to the doctor’s office herself. After she learned that the children were suffering from malnutrition, she visited the children’s father (their mother was dead) and found out that he fed the children mush three times a day. After she left their home, she went directly to see the mayor to get food for the starving children.

We also need a school administrator like Mr. Digby. Brian thought Mr. Digby didn’t act like a principal. But the boy looked up to the schoolmaster and liked to have a heart-to-heart talk with him. The principal had become a father figure to Brian since he lost his father at a young age. Mr. Digby, together with Miss Thompson and Dr. Svarich, fought the town to get Tong and Vooie’s family on relief. When the troubled kid, the Young Ben, skipped school, Mr. Digby visited his home and talked to his mother about her son’s school attendance (his father was completely drunk). After the Young Ben broke into Harris’ hardware store, the principal paid for the articles the boy stole. When the school board suggested that the boy should be sent away to a reform school, Mr. Digby was very much against it.

Both Miss Thompson and Mr. Digby had a sympathetic heart. Both did not have amnesia for childhood. They genuinely liked, understood and respected children. They could easily click with young people. That was probably why they were successful as teachers. Teachers everywhere, do you see some of them in you?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gu Zhenzhen

Gu Zhenzhen, a mother of four and an occasional teacher, lives with her family in Toronto.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Sept/Oct 2017 issue.