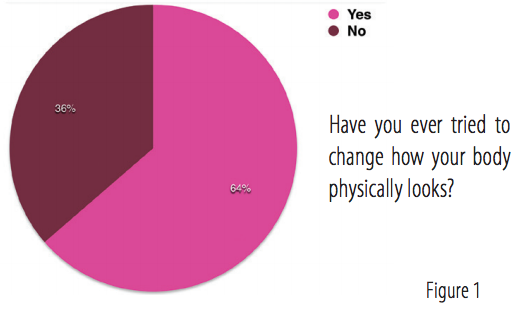

In a 2015 pilot study among 33 females aged 10 to19, it was revealed that 64% of the participants had, at some point, tried to change their physical bodies. Although this study was conducted in Ontario, it has relevance for all Canadian provinces. Eating disorders are now the third most chronic illness in adolescent girls (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2001). Eating disorders are a pressing issue that not only impacts the individuals and families suffering from them, but also places significant strain on the healthcare system, as treatments can be costly. Moreover, in Canada, there continues to be a lack of resources provided for eating disorder treatment and prevention (Standing Committee on Status of Women, 2014). Figure 1 depicts the results of participants’ responses to the question asking if they had ever tried to alter their body.

One factor that contributes to the development of eating disorders is body dissatisfaction, which is caused by various influences including mass media. In today’s society, media has become very pervasive—encountering media is an inevitable part of our lives, as we heavily depend on these platforms for communication and acquiring information about news, history and entertainment. However, with this large presence of media comes extensive exposure to inaccurate and unhealthy messages.

Although body image is a concept that affects both men and women, females have been found to be generally more dissatisfied with their physical appearance than males (Kinlen, 2006). Over the years, media has increasingly placed a focus on the “thin-ideal” (Vonderen & Kinnally, 2012). Further, studies have linked exposure to the media’s thin ideal to body dissatisfaction and eating disorders in women (Ibid., 2012). It can be argued that without the appropriate media literacy skills, children are unlikely to question the validity of the overwhelming number of media messages that they receive.

In a social milieu characterized by unrealistic, yet inescapable messages that are dispensed through various media platforms, it is crucial for children to be able to debunk these distorted ideas. Teaching children how to challenge false messages is important for the development of positive self-esteem, confidence and body acceptance. Ideally, if eating disorder risk factors can be reduced by teaching children these skills, then eating disorder pathology will also be reduced, or prevented altogether (Stice, Shaw & Marti, 2007).

Social cognitive theory suggests that people learn new information and behaviours by watching and replicating the actions of others (O’Dea & Abraham, 2000). If properly trained and motivated, individuals can be taught to become more critical of media and the ideas and beliefs that media disseminates (Ibid., 2000). Media literacy education is a good example of an area where social cognitive theory can be applied, as these skills can be modeled and regulated by policymakers, educators and parents, then imitated and adopted by the students who observe them.

Media literacy has been shown to help mitigate negative body image messages perpetuated in media, as it teaches individuals how to be critical observers who recognize that media messages do not always reflect reality. Moreover, media literacy can be deemed as a primary prevention tool for eating disorders, if utilized properly. As an example of curricula in Canada, Ontario’s media literacy curriculum is presented with the expectation that students will learn how to critically interpret the messages that they receive and “differentiate between fact and opinion; evaluate the credibility of sources; recognize bias; be attuned to discriminatory portrayals of individuals and groups, including women and minorities; and question depictions of violence and crime” (Ministry of Education, 2006). However, media literacy is not explicitly offered to students as a separate course, rather elements of media literacy are incorporated into preexisting courses such as English, Language Arts, Social Studies, and Health and Physical Education. Since media literacy is taught only in a general sense within courses, students are learning how to broadly analyze media, but without a particular focus on body image.

The primary aims of this study were to assess the influence that Ontario’s media literacy curriculum had on adolescent girls between Grades 6 and 12 in relation to their body image; to examine whether media literacy should be taught with specific focus on body image in order to facilitate positive affects; and to consider how the delivery of material might affect different age groups. The hypothesis of this study was that the current media literacy curriculum in Ontario does not have significant influence on improving negative body image ideals in adolescent girls. Therefore, in order to help maintain or improve positive body image ideals in girls, changes to curriculum may be required, specifically by incorporating programming to explicitly focus on issues related to body image such as self-esteem and the thin-ideal.

A literature review helped to identify components needed for addressing negative body image in adolescent girls, such as gender-focused education and content addressing internalization. Other components identified were programs with explicit focus on body acceptance, engagement and older participants. The review also highlighted that information perceived as valuable by participants is an important element needed for addressing negative body image. Although Ontario’s media literacy curriculum does not include elements such as gender exclusivity, explicit focus on body acceptance and delivery by specialists, the curriculum is an example of long-term programming, since students receive media literacy education from Grades 1 to 12.

In the delivery of this study, 33 girls were surveyed, using a two-page, multiple-choice questionnaire from four different platforms. The first page of the questionnaire asked questions that helped with categorization purposes, while the second page provided participants with statements to be ranked using a 5-point Likert like scale, a tool often used in questionnaires associated with body image.

On the first page of the survey, 64% of participants revealed that they had, at some point, tried to change their physical bodies. This question was posed in order to help gauge the severity of body dissatisfaction. Considering the responses, it appears that there is a high level of body dissatisfaction among these participants. Moreover, the age group that most actively tried to alter their physical appearance was 13 to 15 year olds. Interestingly, this group may be the most prone to development of eating disorders as they lie directly in the middle of the age group with the highest eating disorder hospitalization rate in Canada, which are females between 10 and 19 years old (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2014).

Another notable finding from the first page was that each respondent who stated that “media” had the most influence on how she viewed her body also said “yes” when asked if she had ever tried to change how her body looked. This finding reinforces the major influence that media has on body image. This also emphasizes the need for girls to receive substantial media literacy training with emphasis placed on addressing body image, since it appears that general training does not help girls to improve body image ideals.

On the second page of the questionnaire, participants were asked to rate their level of agreement to the statements presented. Among the findings, four particular responses stood out. Statement two said, “I often compare my body to images that I see in the media.” The responses to this statement revealed that 18 participants, or over half the participants in this study, to some extent, compared themselves to the images they view in the media. Statement five said, “The bodies of girls and women in the media are mostly accurate.” Again, responses revealed that over half of the participants in this study felt that the images of females presented in the media were usually true, even though these images are often distorted in reality. The response to this particular question also reinforced the hypothesis of this study, which was that media literacy curriculum requires specific attention to body image, as girls appear to not be transferring the general skills that they are taught to their personal body image views.

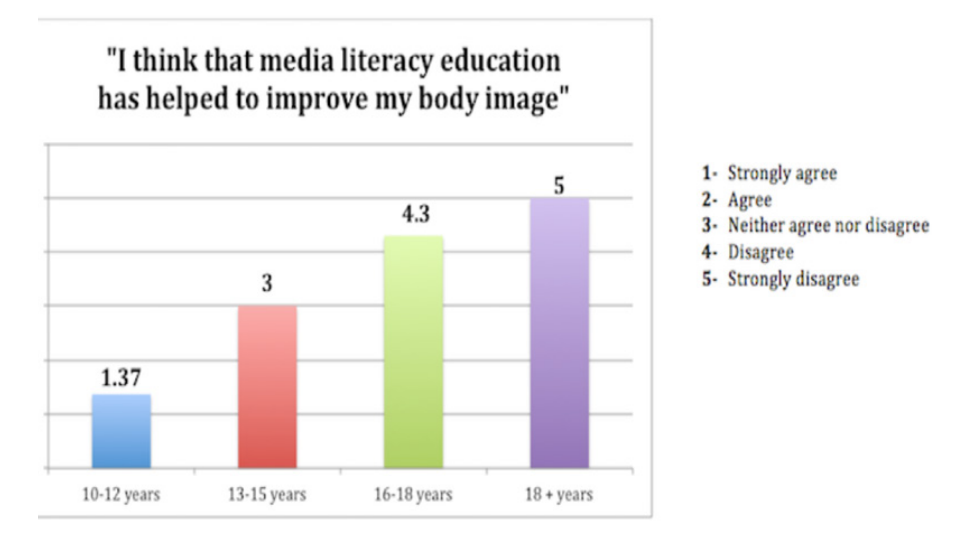

Statement nine said, “I have a good understanding of what media literacy is.” Based on responses to this statement, 13 out of 33 participants felt to some extent, that they did not have a good understanding of media literacy. Statement ten said, “I think that media literacy training has helped to improve my body image views.” Only 10 out of 33 participants, to some extent, agreed that media literacy was providing this benefit. This again shows that media literacy training has not had a positive influence on the body image ideals of a significant portion of participants in this study. Figure 2 displays the average responses to statement ten, in comparison to age groups.

An important finding that was consistent throughout many of the survey responses was that older participants appeared to exhibit less of a connection with media literacy lessons, and generally displayed less body satisfaction than younger participants. Many factors may have contributed to this, including the standpoint of participants or inconsistency in curriculum delivery. Nonetheless, further inspection of these results is needed.

This study highlighted several noteworthy gaps and findings that require further examination. Overall, it appears that the majority of participants, to some extent, express body dissatisfaction, and moreover, these girls are not applying the critical media skills that the Ontario media literacy curriculum aims to provide. Given these findings, six policy recommendations have been formulated that touch on the merits of research, formalized reviews, assessments, redevelopment of delivery, body image focus, and curriculum consistency and monitoring. Specifically, these recommendations assert:

- The Ontario Ministry of Education should consider facilitating a comprehensive examination, evaluating the effectiveness of the present media literacy curriculum. This examination would not only help to fill in the shortcomings revealed by this study, but may also reveal other significant findings that can be used to create positive and substantial changes.

- In conducting this comprehensive examination, the Ministry of Education should enlist support from the Ontario Education Research Panel, given the Panel’s ability to facilitate further discussion, enable various collaborations and utilize results.

- The Ontario Ministry of Education should encourage ongoing feedback from students and educators on the effectiveness of media literacy, as this encourages inclusivity, and helps to gauge if students perceive materials to be valuable.

- The Ontario Ministry of education should consider a less fragmented approach towards the delivery of media literacy curriculum. Presently, media literacy lessons appear to be unevenly distributed amongst different subjects. However, if media literacy receives a more defined presence in curriculum, this may strengthen the delivery of its objectives.

- Body image should be a required element to be taught, as this would ensure that students, particularly girls, make connections between media literacy and personal body image.

- Finally, in regards to structure and monitoring, a less fragmented approach for media literacy should be considered, as well as specific, mandated measures or lessons plans for educators to follow. This would help ensure consistency, in the delivery of curriculum, as well as strengthen the delivery of objectives.

This study was limited by factors such as time constraints, data-collection methods, access to participants and small sample size. Given the parameters of this project, this study lacked statistical significance, meaning that the results cannot be used to make generalized assumptions about girls in Canada. However, it can be viewed as a pilot, or tool of reference for future research, as the findings helped to shed light on a specific area that appeared to not have been examined.

Comprehensive examination is needed to fully assess the influence that media literacy curriculum has on body image, for adolescent girls in general. Before girls can become truly critical about media and the distorted images that media disseminates, policymakers and educators first must place critical attention on ensuring that media literacy skills are effectively being delivered within Canada’s educational curriculum.

References

Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Standing Committee on Status of Women. (2014, November). Eating Disorders Among Girls and Women in Canada. 4th Report. 41st Parliament, 2nd Session. Available: http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=6772133&Languag e=E&Mode=1&Parl=41&Ses=2

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2014). Use of Hospital Services for Eating Disorders in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.cihi.ca/web/ resource/en/eatingdisord_2014_infosheet_en.pdf.

Kinlen, A. D. (2006). Self-perceptions and body image in preadolescent girls and boys (Doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University).

Ministry of Education. (2006). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 1-8 Revised: Language. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/ elementary/language18currb.pdf.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11 and 12: English. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/ secondary/english1112currb.pdf.

Ministry of Education. (2013). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 1 to 6: Social Studies and 7 to 8: History and Geography. Retrieved from http:// www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/sshg18curr2013.pdf.

Ministry of Education. (2015). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 1 to 8: Health and Physical Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov. on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/health18curr.pdf.

Ministry of Education. (2015). The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 to 12: Health and Physical Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov. on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/health9to12.pdf.

O’Dea, J. A., & Abraham, S. (2000). Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: A new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(1), 43-57.

Ontario Education Research Panel. (2013). Mission, Purpose and Strategies. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/research/OERP2013.pdf.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Marti, C. N. (2007). A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: encouraging findings. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol.,3, 207-231.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tierra Hohn

Tierra Hohn is a recent graduate from Carleton University’s Public Affairs and Policy Management program. For her honours thesis, she chose to conduct a pilot study looking at the Influence of Ontario’s Media Literacy Curriculum on Body Image in Grade 6 and 12 girls. Tierra Hohn is also a body image enthusiast, workshop facilitator, and overall promoter of health and happiness. If you are interested in reaching out, please feel free to contact her either through her e-mail address: tierra.hohn@hotmail.com, her blog: tierrahohn.weebly.com, or Twitter: www.twitter.com/tierrahohn.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Sept/Oct 2015 issue.