Managing a classroom can be very challenging; put a child with behavioural issues into the mix and you’ve got a whole new set of challenges; put a child with behavioural issues as a result of ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder) whose medication doesn’t seem to be working—well that’s another story all together. But the story doesn’t have to end there.

One of the most recognized causes for behavioural problems amongst school-age children is attributed to ADHD. This is a medical condition that affects three to five percent of all children, which means that an average class has at least one student with this disorder.

The medication for ADHD is supposed to settle a child down emotionally, making them more manageable and more focused toward learning, but if they continue to monopolize much of a teacher’s time and energy, there’s a good chance the child’s medication isn’t working. Why is this?

It’s likely because ADHD has been incorrectly diagnosed.

This is understandable when you consider that many symptoms often ascribed to ADHD are common to, or overlap with Central Auditory Processing Disorder (CAPD). There are however, many that don’t belong to ADHD.

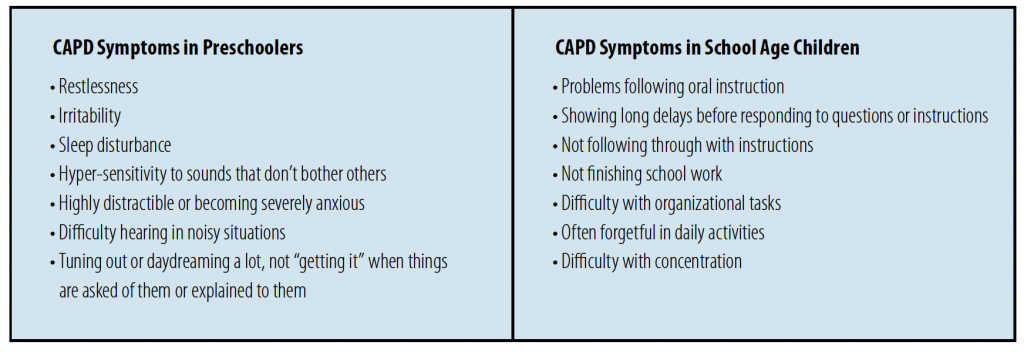

Symptoms of CAPD include:

There is another reason why professionals often confuse ADHD with CAPD and other learning disabilities.

Very few people realize that there is a process inside the brain known as “auditory processing.” Auditory processing is the mental activity in which auditory signals that have been sent to the brain by the ears are processed and understood. It is the part of hearing in which sounds and words are comprehended as having meaning.

What is it like for someone who has an “auditory processing” problem? If you’ve ever tried to talk on the phone while someone in the same room was watching TV with the sound turned up, you know something of the feeling that people with CAPD may experience all of the time—an endless tiring struggle to try to concentrate on what’s happening through relentless background noise.

As soon as I say the word “auditory,” everyone assumes that I am talking about hearing. But hearing is not the same thing as understanding what you hear. People who have CAPD can often hear perfectly well, but they have trouble making sense of what they are hearing. Their ears function normally, but the auditory centres deep inside the brain do not. So, for example, a person with CAPD may have trouble hearing the difference between “I’m” and “fine,” or “mean” and “need.” And this means they are going to have problems handling everyday social life.

But what is most significant about someone with CAPD is that they don’t know they have it; they think that what they hear is the same as what everybody hears.

It’s confusing for them because they get low marks, are rejected socially and don’t understand why, therefore they conclude that it must be because they’re stupid. What makes things worse is that due to the similar behavioural symptoms, CAPD is often confused with and diagnosed as Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD).

For instance, one of my students, Matt, now 12 years old, who prior to coming to me had received a firm diagnosis of ADHD, had been given eight different medications over six years in an attempt to control the disorder. But none helped.

Matt was frustrated and becoming a behavioural problem at school. An earlier psycho-educational assessment when he was six years of age, diagnosed him as gifted with possible ADHD. He was later referred to me because his medication wasn’t helping, his marks were dropping, and he didn’t believe he was smart or capable of getting good marks. When he came to me, he wasn’t prepared to do his homework, because he felt it was pointless.

Upon completion of my testing, I confirmed that there was no question that Matt was gifted. I also discovered that he had a very severe CAPD. So severe, there was only one direction he could go, and that was up. After three months of treatment, upon reassessment, his CAPD had improved greatly, well into the above-average range. He was excited. He decided to continue, and after another two months, he was reassessed again, which included his auditory processing and reading comprehension.

Before I told him his scores, I asked him if he felt any difference.

“I can listen now, and I understand what the teacher is saying,” says Matt. “I’m getting 80s and 90s in all my subjects, and now I believe I am gifted!”

Matt went from the 1st percentile on the test for auditory processing to the 97th, and from the 58th percentile in reading comprehension to the 96th.

I don’t know who was more emotional, him or me. And I don’t know what made me more emotional, his response or his scores—I believe it was his response.

CAPD can be corrected, doesn’t require medication, and to avoid or reverse many of the behavioural and negative effects, early detection is best.

So, if a child is experiencing some of the symptoms listed above, is distracted or unusually bothered by loud or sudden noises, has trouble following directions, whether simple or complicated, or you observe that conversations are hard for the child to follow, it would be wise to suggest they seek further professional assessment. The decision to do so just might be the difference in a student’s success—perhaps for the entire class.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Deborah Chesnie Cooper

Dr. Deborah Chesnie Cooper is an educational and developmental psychologist with degrees from York University and The University of Toronto who has been in private practice since 1972. She is President of dEcode® Learning Systems Inc. Research, Director of The Chesnie Cooper Educational Centre, and serves as a member of the Board of Governors, Mount Sinai Hospital. Contact Dr. Chesnie Cooper at The Chesnie Cooper Educational Centre: 416-322-3161 or chesniecooper@bellnet.ca

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s January 2009 issue.