Can You Spot the Difference?

We want our students to be critical thinkers. So, in my classroom, my lesson on fake food and fake news begins with glossy images of syrupy pancakes and ice cream cones. Then I ask, “Who can spot the fake? Who sees the potatoes?”

Commercial photographers don’t just capture images. Their real job is to manufacture the ideal. They physically create innovative, fabulous fakes—and while we love learning their tricks, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Today’s digitized content, social media, fiction, non-fiction, and our interactions with them move at lightning speed. However, the images and information shared rapidly and globally are increasingly opportunistic or false. It’s a precarious landscape for our students to navigate. We must teach them to be critical thinkers and discerning consumers of products and of information.

We cannot always believe our eyes. We must not assume all our screens tell the truth. I urge my students to question the source, the purpose, and the relevance of information—articles, movies, websites, textbooks, lyrics, ads. All of it. We start with eye appeal.

The advertiser’s world of fake food uses varnish, hairspray, and lip gloss to make candies, fruits, and vegetables appear luscious and fresh. This trick also lets products withstand long photo sessions under bright lights. To make meat look perfectly roasted or grilled they use shoe polish and spray-tan. French fries are pinned into position for flawless, symmetrical displays. Tiered food like pancakes, burgers, and desserts are stacked twice their actual height with foam discs inserted between the layers. These are standard gimmicks. Bigger and brighter is better. It makes our mouths water. But misleading us visually creates false expectations, which, subsequently, alter our choices and spending. That is the real motivation for the food image manipulation.

It is picture-perfect. Cereal and berries floating in pure white milk tantalize viewers. Ads show gooey cheese stretching endlessly as a pizza is pulled apart. They don’t use real dairy though. They use Elmer’s white glue. The same glue students use in Grade Two. It is more dense and viscous than real milk. It photographs better and consumers respond to it more strongly. The fakes are effective, but they are too good to be true.

Students love learning about the trickery. They recoil when learning that engine oil is used in place of maple syrup. It won’t absorb into food and it puddles perfectly for photos. Liquid soap is added to glasses of beer or soda to make more stable and impressive foam. Advertisers drop Aspirin into carbonated drinks to exaggerate the effervescence. And what’s the standard replacement for whipped cream? Shaving cream. In reality, whipped cream melts and spatters so photoshoots crown cake or pie with dollops of shaving cream instead. The fake cream is denser, more durable, and more desirable.

How do fakers craft perfect ice cream? They use instant mashed potato powder, water, and dyes. Then they scoop or sculpt whatever they desire—no melting, no drips. Glycerol spray can make glasses of drinks seem “sweating” and ice cold. Dry ice chips tucked in and around meals or mugs contrive “steaming” hot images. Advertisers know these visual cues make us salivate. The fake photos work. We react. Companies sell more products. Once society is trained to accept, prefer, and expect the fake food (the unrealistic, perfect image) how long until this seeps into other fields? Fake food is one thing. Fake news is another.

How do fakers craft perfect ice cream? They use instant mashed potato powder, water, and dyes. Then they scoop or sculpt whatever they desire—no melting, no drips. Glycerol spray can make glasses of drinks seem “sweating” and ice cold. Dry ice chips tucked in and around meals or mugs contrive “steaming” hot images. Advertisers know these visual cues make us salivate. The fake photos work. We react. Companies sell more products. Once society is trained to accept, prefer, and expect the fake food (the unrealistic, perfect image) how long until this seeps into other fields? Fake food is one thing. Fake news is another.

I repeatedly remind colleagues and students that just because Google gives you a website, you must not assume the information is accurate. In fact, search engines alter the options and links offered to you based on your location and previous search history. What does this mean for truth and accessibility? Images and data found online can be just as artificial and misleading as foam pancakes with oil syrup or spray-tanned turkey dinners. Today’s students are digital citizens. We must equip them to be critical consumers of both products and information because where fake food constructs an ideal, fake news promotes the unreal.

Fake news is also labeled disinformation, pseudo-news, and yellow journalism. It is fabricated content presented as fact. Our digital economy, ubiquitous screens, and the worldwide web have conditioned populations to expect limitless information and immediate gratification. Certainly, the Internet is an incredible tool for democratization and education. However, it is also proving to be a haven for fraud and manipulation.

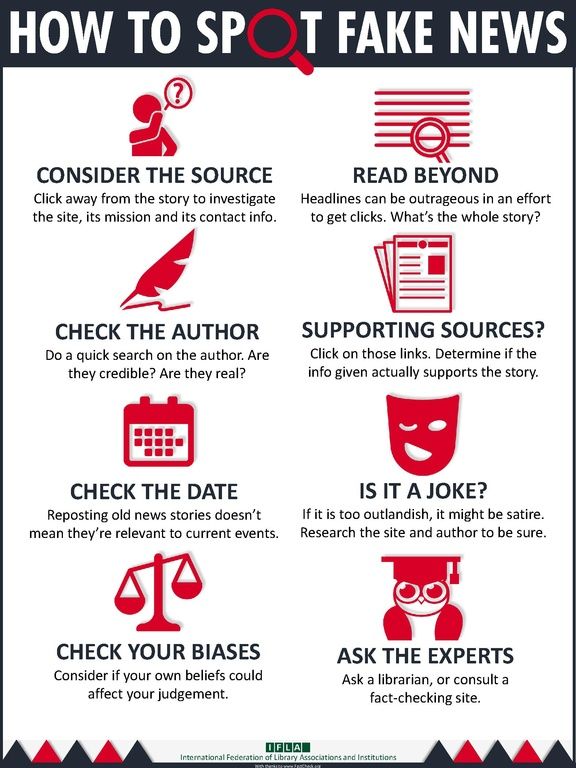

As a Literature and History teacher, I’m well aware that rhetoric and propaganda have manipulated social and political messages since ancient times. However, with today’s social media, a tsunami of trickery and fabricated stories can go global within minutes! Just as mashed potato gets sculpted to look like perfect ice cream cones, fake news stories are designed to look like traditional news. It is vital to question the source, the purpose, and the relevance of the information we ingest.

Traditional journalists research issues, conduct interviews, corroborate facts, and edit their text before things get published. These are the same skills that we teach our students. However, fake news can be created and uploaded by anyone, anywhere, without peer review or editing. What is worse, many fake news stories are generated with intentional errors, contradictions, and inconsistencies. They do damage. Often, they are motivated by malice, mischief, or profit.

People and agencies get glamorized or demonized. Political campaigns can be derailed. Vaccine programs are undermined. Photographs are doctored. Maps might be inaccurate. As social hoaxes flourish, citizens and consumers are misled. When I ask my students to generate examples, class discussions spring to life!

There are content creators and website designers who are paid to push conspiracy theories, promote specific loyalties or purchases, distort reality, and even stoke or provoke conflict. Their fake news gets retweeted and repeatedly shared on social media. It even spills into mainstream media. Fabricated stories gain traction and get consumed by millions of people in mere moments. It’s both fascinating and horrifying, and it is the reality our students face.

With global politics and the pandemic, we’re experiencing a worldwide onslaught of radical stories, claims, and facts. Some are legitimate. Many are contrived. So I urge my students to assess things critically. Is the information or fact something they can confirm or corroborate? Is someone specific benefitting from them using or believing the data? Who and how?

Public images and information are frequently designed with ulterior motives in mind. There is enormous potential to influence opinions, purchases, and votes. Our online search histories and profiles are tracked, shared, and sold. It’s called “scraping.” Once we use apps, browse store websites, make online purchases, view YouTube or Netflix, our screens repeatedly prompt us to “try similar shows such as…” They bombard us with ads akin to previous searches or purchases. They “customize” the options we get next time. Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms do much more than monitor our habits. They are changing them.

Students need to learn new vocabulary. Malware is software designed to exploit systems and devices. Phishing scams and clickbait mislead individual users. Cookies are files that track and alter your browsing history. Beacons, bugs, and tags count and collect your personal data whether you know it or not. The buzzwords at tech companies today are surveillance, disinformation, and monetization. Accessing information makes us the data that information producers and marketers desire. We all need to be aware of their strategies and subversion. The line between real and fake, fact and fiction, is blurring as we speak. Students need extra tools and skills. They must learn to be discerning. They have more media options and sources of information than any generation before—but fake food and fake news abound. Truth is rarely on the surface. It’s not about conspiracies or complacency. It’s about thinking more critically—every day. That picture-perfect ice cream may actually be potato. Once you show students the trickery, they will be much more alert.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maria Campbell

Maria Campbell (OCT) teaches at Lester B. Pearson High School in Ottawa. She is a firm believer in equipping students with Global Competency skills, especially thinking critically. She has traveled and taught abroad, is a wife and mother, and also writes fiction and non-fiction.

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Fall 2021 issue.