One of the most awe-inspiring as well as critical achievements of young children is their early effort at making and conveying meaning via print. It is a complex process that requires mobilizing linguistic, cognitive and neuromotor resources that generally coalesce in the second half of Grade 1 and through Grade 2. This leap to written literacy is often misunderstood, and teaching practices do not target the underlying concepts and skills that are foundational to later literacy development. As a result, too many young learners are not meeting acceptable benchmarks by the end of Grade 2 in their early literacy achievement. This article identifies and unmasks four persistent myths surrounding early written literacy learning, and provides ideas for instructional approaches that will enhance literacy achievement for those youngsters whose needs are currently being overlooked. Like a puzzle, these myths are interconnected and need to be addressed together in order to make a lasting impact on children’s literacy development.

MYTH #1: Learning to print is natural and easy, and can be learned in the context of rich, authentic and engaging literacy tasks.

What teachers need to know and do: Printing is a complex skill that involves recognizing and practising space, shape, size and speed of letter formation. Like any skill, it is best learned through direct, explicit instruction with specific feedback and encouragement as children make progress. Regular, consistent, short periods of time—perhaps 20 minutes daily, beginning in the second half of Grade 1 takes advantage of the sensitive window when the neuromotor and cognitive mechanisms are “ready” (Roberts, Derkach-Ferguson, Siever, & Rose, 2014). Practice is important! This can be orchestrated in a variety of ways that promote enjoyment and a sense of pride of accomplishment.

As a staff team, choose a developmentally progressive, engaging, programmatic approach that you can implement consistently from K through Grade 2, so that children hear and practise with the same wording and instructional approach as they learn to print. Commercially available programs or programs available online (free of charge) can all work well. Find one that fits with your literacy framework and the teaching approach at your school.

Printing, or “language by hand” leaves memory traces on the neuro-circuitry that enhances learning. Kinesthetic engagement of little fingers and hands has a profound impact on learning that is only now becoming better understood in education, thanks to current research in the neurosciences (Konnikova, 2014). There are no shortcuts or substitutes for either learning to print manuscript or write cursive style.

MYTH #2: Children can “invent” spelling and gradually self-correct as they intuit the conventions of spelling.

What teachers need to know and do: Our spelling system is an ingenious gift of our literate history that needs direct teaching through a variety of pat-tern-seeking tasks, games, phonics instruction and memory work (aided by mnemonic devices or strategies for remembering). Children can benefit from spelling instruction as early as Grades 1 and 2. Again, choose a developmentally progressive, programmatic approach to teaching spelling, whether commercially prepared or available from the Internet. As with printing, regular but relatively short lessons work best: start early and avoid the much tougher work down the road of having to undo ingrained errors and habits that detract the reader from engaging with the content, and can result in lower marks allocated for the work in high school and university.

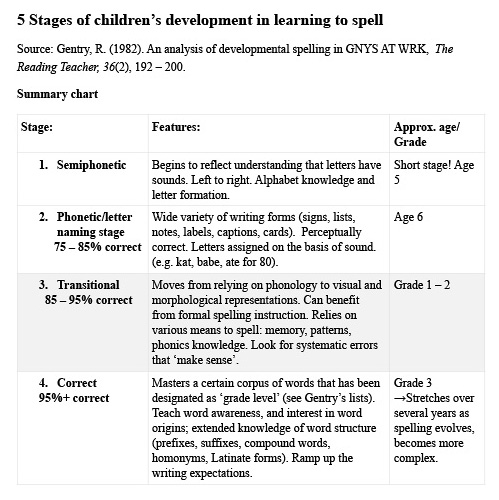

The Figure below that I have adapted from Gentry (1982), provides a summary of what to look for.

Of course, children should be encouraged to take risks by applying phonics knowledge to attempt words they know but haven’t quite “nailed.” The writing sample, from the end of Grade 2, illustrates these points. Both spelling and printing need to be automatized sufficiently to make working memory space available for the retrieval of “juicy words” that enhance the writing effort.

MYTH #3: Vocabulary learning will occur as a consequence of immersion in a language rich learning environment.

What teachers need to know and do: Children can and do learn language through immersion and massive amounts of comprehensible input—a term coined by Krashen (1982) to describe the level of language required for students to benefit and to learn from exposure. But many linguistically vulnerable students, including those raised in poverty and those who are English as a second language learners, require more: direct explanations, providing definitions and manipulated text that makes vocabulary learning salient or “noticeable.”

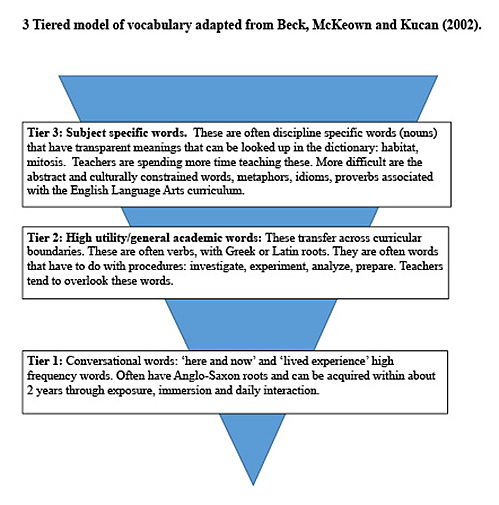

Beck, McKeown and Kucan (2002) advance a three tiered model for thinking about targeting vocabulary teaching.

While teachers are attending more often to the subject specific vocabulary in their instructional planning such as the word habitat (i.e., Tier 3), it is the general, high utility academic vocabulary that travels across curricular boundaries that is being overlooked (i.e., Tier 2).

Children can benefit from vocabulary learning strategies such as analyzing words for their roots and inflected forms. In addition, learning the meanings of Greek and Latin roots helps all students access the academic words in the content areas, especially Science and Social Studies. Word study and word play with flash cards can help develop speed in word recognition, a skill that is equally important in developing reading fluency. Children often enjoy keeping personalized collections of flash cards, and devising games that involve scoring points for knowing definitions, including Scrabble games and crossword puzzles that teachers can readily create online with programs such as Puzzlemaker. For younger students, allow access to the flash cards as a scaffold for participating in these learning tasks and games.

To summarize the myths discussed so far, think of a puzzle of interconnecting pieces. Early literacy development is akin to putting the puzzle together for young learners, as they work hard to control and master printing, spelling and vocabulary knowledge.

To summarize the myths discussed so far, think of a puzzle of interconnecting pieces. Early literacy development is akin to putting the puzzle together for young learners, as they work hard to control and master printing, spelling and vocabulary knowledge.

The fourth and final myth involves the ongoing controversy surrounding the teaching of cursive writing versus keyboarding. In my view, it is not a question of either/or but rather, both/and in a balanced approach that prizes traditional literacy as well as digital literacies related to the use of technology in a fast-paced, connected global community.

MYTH #4: Cursive writing is not necessary. 21st century literacy and the ubiquity of digital devices require keyboarding skills instead.

What teachers need to know and do: This is probably the most entrenched and difficult to address of the myths. Many jurisdictions across Canada, the US and internationally (Must, 2014), have abandoned the instruction of cursive writing in the curriculum, believing that keyboarding can replace writing and is more in line with contemporary literacy practices. A growing body of research emphasizes the hand-brain connection and the speed of processing required as children advance to Grade 3. For example, a strong piece of writing at the end of Grade 2 comprises 190 words (Roessingh & Elgie, 2014). One year later, at the end of Grade 3, strong writing comprises 265 words written in the same amount of time (Roessingh, Scott & Wojtalewicz, 2016). In these studies, corroborated by other researchers, the number of words on the page correlate with the quality of writing. Connecting script is the solution to increasing speed and in turn, volume, without sacrificing brain engagement. Scarce and fleeting working memory is better used for retrieving vocabulary and organizing the text.

Writing demands increase in complexity and volume with each year of schooling. Literacy engagements require note-taking, summarizing, argumentation and persuasive and creative writing, all of which require automaticity and speed to succeed. Morrow (1986) via the persona and voice of Mr. Toad reminds us why being able to write lies at the conceptual heart of what it means to be literate. Coyne (2013) further explains the power of language by hand. Schools can adopt a programmatic approach to the teaching of connected script. Various styles are available to choose from. Though most practitioners might recognize D’Nealian script, Marion Richardson script offers an alternative: it is not a big step from manuscript to cursive. Some young students take this step spontaneously, however, in my research work I note that the vast majority of students even at Grade 4 to 6 are still printing and are unlikely to make the shift to cursive style without instructed support. And it appears to be holding them back as their thoughts outpace their hands, especially in the case of gifted learners who have so much they want to put on the page.

Marion Richardson script, below, illustrates the small nudge it would take to connect and in turn, speed up written production for young students in Grade 2 or 3.

Of course, keyboarding skills do become increasingly important in school work, however, it is important to underscore two points. First, better writers become better at keyboarding since, once mastered, the foundational skills of printing, writing and spelling transfer to keyboarding; and secondly, as Mr. Toad explains, those who can do both have options available that those who depend on keyboarding do not.

A small minority of children may not be able to develop the neuromotor capacity to learn to print in Grade 2 or 3. The unending frustration for them, their teachers and their parents requires thoughtful intervention, including the shift to keyboarding at a point where it becomes clear that further insistence on printing practice will be fruitless.

For all children, instruction in keyboarding is very important to avoid developing habits that will interfere with fluency later on (i.e., “hunt and peck” method). As with printing, there is a latency period where output speed is slow—yet another reason to have “language by hand” as the default option for most young students at least until upper elementary grades.

Concluding Thoughts

Myths surrounding early literacy learning persist and are pervasive in the thinking of many teachers, parents, administrators, policy makers and the scholarly community because there is an element of truth embedded in them, and they have intuitive appeal. The term, “digital native,” for example, holds the promise of never again having to face the tedious task of pushing a pencil for future generations of young children who will complete and turn in all of their work by way of computer (Prensky, 2013). Other voices and new research from the neurosciences suggest this would be a mistake, for reasons outlined in this article.

My intention is to provoke lively discussion, debate, rethinking and reflection about early literacy teaching and learning with the goal of transforming pedagogy in the early years. These changes may require some professional development for primary school staff members. Approach your local professional councils to support and provide for your professional learning needs. Scout the Internet for accessible journal articles to provide the background academic readings and theoretical underpinnings for questions you have about early literacy development. Enrol in an online course for possible enhanced teaching credentials. And don’t do it alone! Many school jurisdictions encourage and provide time for teachers to belong to a community of practice (COP) or a professional learning community (PLC) intended to afford a supportive, collaborative environment for studying student work and seeing their efforts as data that can bridge practice to theory and in turn, to enhanced practice or “praxis”: pedagogy that is informed and impactful.

References

Beck, I., McKeown, M. & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford.

Beer, A. & Meyer, C. (20111). Cutting Cursive, The Real Cost: How Replacing Cursive Instruction with Keyboarding Fluency in Elementary Schools Hampers Brain Development. http://mimlearning.com/cutting-cursive-the-real-cost/

Coyne, A. (2013). How we write affects what we write. http://o.canada.com/news/national/putting-words-down-on-paper-how-we-write-affects-what-we-write

Konnikova, M. (2014). What’s lost as handwriting fades? New York Times, June 2, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/03/science/whats-lost-as-handwriting-fades.html?_r=0

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Morrow, L. (1986). Scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Toad. TIME magazine, February 24, 1986.

Must, M. (2014). Schools will start teaching typing instead of longhand. Helsinki Times, Nov. 20, 2014. http://www.helsinkitimes.fi/finland/finland-news/domestic/12767-schools-will-start-teaching-typing-instead-of-longhand-2.html

Prensky, M. (2013). Shaping technology for the classroom. Edutopia, Dec. 14, 2013. http://www.edutopia.org/adopt-and-adapt-shaping-tech-for-classroom

Richardson, Marion.

Roberts, G., Derkach-Ferguson, A., Siever, J. & Rose, S. (2014). An examination of the effectiveness of Handwriting Without Tears® instruction. Journal of Occupational Therapy 81 (2), 102-113.

Roessingh, H. & Elgie, S. (2015). From thought, to words, to print: Early literacy development in Grade 2. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60 (3), 576-597. http://ajer.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ajer/article/view/1508/pdf_16

Roessingh, H., Douglas, S. & Wojtalewicz, B. (2016). Lexical standards for expository writing at Grade 3: The transition from early literacy to academic literacy. Language and Literacy. Revisions submitted, June 29, 2016. Accepted. www.langandlit.ualberta.ca/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hetty Roessingh

Hetty Roessingh, PhD is a professor at the Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary. She taught Grade 7 – 12 English as a second language for 29 years before accepting a faculty position in Education. Over the past 17 years, her program of research has focused on language and literacy learning for students across Grades 2 to 12, and the transitional academic demands of university level studies.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Jan/Feb 2017 issue.