Art teachers are often called upon to supply institutional graphics. I have always prided myself in creating eye-catching newsletters, flyers, programs and newspaper advertisements for my school. I reasoned that it cost the same dollars to print something poorly designed as it did to print something that looked good. I also believe that every printed piece distributed is a reflection on what is going on in the building—and that our community forms opinions based on the material they receive and the images they see. That is even more true today as these images gain so much more currency when posted on the Internet.

As I reflect on a career of more than thirty years in public education, it is interesting to see how the technology to create information design has evolved.

As I reflect on a career of more than thirty years in public education, it is interesting to see how the technology to create information design has evolved.

I was fortunate to attend Fisher Park High School, where my art teacher, the late Willie McKay taught us the art of silkscreen printing. At that time, the fabled spirit duplicator and the messy Gestetner stencils ruled—and when Willie and his commercial art experience arrived on the scene, the visual impact of his craft immediately captured everyone’s attention. Silk screening’s signature is bright, flat, opaque colour—and since we had screens of all sizes, the posters we created always eclipsed the common 8.5 x 11 and 8.5 x 14 threshold. Willie taught us how to carefully hand cut Ulano StaSharp film and how to register colours. As we progressed, he passed on other stencilling techniques including the use of photographic emulsions.

My studies at the Ontario College of Art exposed me to further experimenting with the poster genre through projects with acclaimed Canadian graphic designers Jim Donoahue and Ken Rodmell. I also discovered the magnificent work of Theo Dimson and Ottawa’s Neville Smith, whose silk screened Black Cat Café poster remains a personal icon. At OCA, I also had the opportunity to create several serigraph editions and improve my silk screening technique.

When I arrived at my first teaching gig at A.Y. Jackson Secondary School in Kanata, Ontario in 1978, I brought my squeegee with me. By this time, photocopiers were in every school, but even though their reproductions were cheap, they could not visually compete with the impact of a silkscreened image. I later moved to Confederation High School when an art coordinator’s position became available.

When I arrived at my first teaching gig at A.Y. Jackson Secondary School in Kanata, Ontario in 1978, I brought my squeegee with me. By this time, photocopiers were in every school, but even though their reproductions were cheap, they could not visually compete with the impact of a silkscreened image. I later moved to Confederation High School when an art coordinator’s position became available.

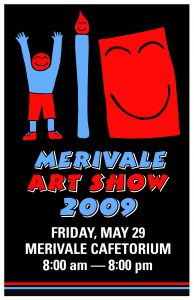

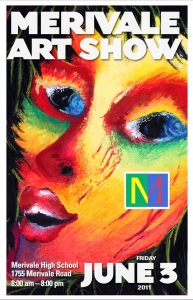

The posters created for our school art shows and events were designed by students, who pulled editions of 50 to 100 and distributed them in the school and throughout the community. Students and staff looked forward to getting their own copies of the limited edition show posters every year.

Unfortunately, the silkscreen process had some downsides, and as schools and teachers became more aware of the health and safety issues associated with solvents, oil-based ink and poor ventilation, silkscreened posters became harder to justify. Water based inks were an option, but they proved difficult to manage and presented their own problems with stencil making and cleanup.

The closure of Confederation High School meant the end of the large industrial sink and pressure washer I used to manage the process. When I arrived at my new post at Merivale High School, I knew that my silk screening days were probably over and that it was time to embrace more modern technology.

The closure of Confederation High School meant the end of the large industrial sink and pressure washer I used to manage the process. When I arrived at my new post at Merivale High School, I knew that my silk screening days were probably over and that it was time to embrace more modern technology.

Offset lithography proved a reliable, albeit more expensive option, but because of the expense, we were always limited to printing in one or two colours. We employed the use of spot colour and duotones effectively to maximize our palette and took advantage of larger sheets of coated paper and longer press runs.

I had already embraced the Mac, desktop publishing and image editing software in my classroom and had the technology to generate 13 x 19 inch artwork on our Epson 1280 inkjet printer. This would not prove to be practical in making a large number of posters, but served as a fitting introduction to the world of digital printing which held a significant economic advantage over offset technology and screen printing in that, the number of colours used would no longer be a factor in the cost.

We experimented with colour laser printing, and although costly, prints could be generated much like a regular photocopy.

Today, it is possible to create artwork using Quark XPress or inDesign, Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator and generate a high-resolution PDF file that can be opened on any computer and printed anywhere.

Today, it is possible to create artwork using Quark XPress or inDesign, Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator and generate a high-resolution PDF file that can be opened on any computer and printed anywhere.

With my students, I can now supervise the creation of posters and have them printed very economically by sending the files to our school board’s Print Services. The process is restricted to a tabloid 11 x 17 format, but I am able to secure terrific results without leaving my classroom, and the printed posters are usually dropped off within a two-day window, to everyone’s satisfaction.

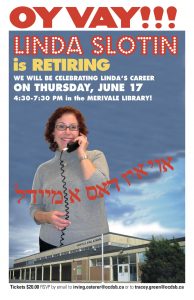

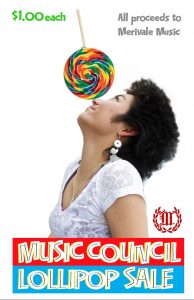

My responsibility centre has shifted and I now find myself department head for all the arts. The digital revolution could not have come at a better time as I find myself continually helping colleagues by creating theater, music, art and event posters.

When we have to broach the tabloid format, our lengthy partnership with Custom Printers of Renfrew has always served us well. They have a digital press that is capable of printing to larger dimensions and if the event being promoted warrants that step, we do so.

When we have to broach the tabloid format, our lengthy partnership with Custom Printers of Renfrew has always served us well. They have a digital press that is capable of printing to larger dimensions and if the event being promoted warrants that step, we do so.

Because no conventional pre-press, inking, plates or press maintenance are involved, digital printing is significantly cheaper and although the quality is not quite the same as high fidelity offset lithography, the gap between the technologies is narrowing every year. The flat colour on the finished digital work actually shares many of the properties of those wonderful silkscreened posters I printed by hand in another time and space.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Irv Osterer

Irv Osterer is currently the Head of Fine Arts at Merivale High School in Ottawa, where he also coordinates the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board’s Communication and Design SHSM/ Focus initiative. He is the recipient of the OCDSB’s Director’s Citation, Fine Arts Leadership Award and a winner of the Ottawa Centre for Research and Innovation (OCRI) National Capital Educator’s Award and the Marjorie Loughrey award for lifetime achievement in the arts by the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Jan/Feb 2012 issue.