Before I begin, I want to clarify that I am not a visually impaired teacher. I am a mainstream educator who teaches

mathematics in a public high school in Montreal.

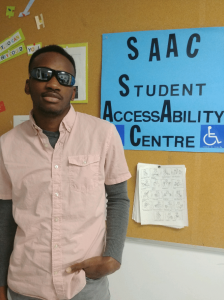

This article is about one of my recent students—someone who is funny, intelligent, bright, determined, focused, and blind. It is about the frustration and shortcomings of a teacher in a mainstream high school who was given the challenge of working with a student who is visually impaired. It is about how I overcame my own inhibitions and how I gained new insight by interacting with a visually impaired student. Last, but not least, this essay is about how this student helped me grow as an educator and overcome my own invisible disabilities.

This article is about one of my recent students—someone who is funny, intelligent, bright, determined, focused, and blind. It is about the frustration and shortcomings of a teacher in a mainstream high school who was given the challenge of working with a student who is visually impaired. It is about how I overcame my own inhibitions and how I gained new insight by interacting with a visually impaired student. Last, but not least, this essay is about how this student helped me grow as an educator and overcome my own invisible disabilities.

I think all teachers would agree that, at the start of each academic year, we are thinking about how we can best create an inclusive classroom for all our students. As teachers, we know how beneficial it is for students to be learning in an inclusive classroom, and we try to adapt our pedagogical toolkit to best deal with the unique classroom environment created by a new batch of students each year. This past year, however, my beginning of the year reflections were given an unexpected jolt when I was told that I would have a student in my classroom who is visually impaired. Imagine yourself in a similar situation, in which, like me, you have been teaching math or science students for several years, in the public and private systems and in different countries, yet had never had to deal with the challenge of teaching a visually impaired student. What thoughts and emotions would go through your mind? Despite your years of teaching experience, would you not feel panicked, burdened, and, may I also add, frustrated at the thought of how you would have to rewrite your teaching plans for the entire year?

That unseen challenges come with teaching a student who is blind was something I did expect, what I did not foresee was the additional hours I would need to spend in reading the available materials on how to teach a student who is blind

and trying to apply those methods to see which one suited my student the best. Blind students are, of course, individuals like any other student, and the one-size-fits-all type teaching methods do not work for them, just as they do not work for mainstream students!

I soon realized that all the resources I needed to help my new student were not readily available. So I took it on myself to make the learning materials that my student needed to use the next day in class. I could not wait for the Center of the Blind to make the resources available for my student. He needed the supplemental learning materials, braille textbooks, and typed class notes to understand the content being taught in class now! Thus, it became my responsibility to ensure all the notes and questions were provided to him so he could learn alongside his peers.

I often had to type class notes for my student to read on his braille reader. I would also type the example questions to enable him to keep up with his peers and tackle the same problems they were solving in class. I had to adapt my pedagogical style too. When I would ask the class to look at the board and tell me what they see, I would internally admonish myself for my choice of words. “What do you all see on the board?” is a common question used in classrooms. But I could no longer assume that everyone in my classroom could see the blackboard. Instead, I started reading questions I had written on the blackboard out loud, to the point I found myself even saying, “brackets, to the power of,” when I started reading the equations on the board.

In addition to typing notes prior to the lesson, I would make graphs on corkboards using many pins and rubber bands. When I would be discussing a graph, an equation drawn on a graph, or even a shape, I would ask my student if I could draw the image I wanted him to imagine on the palm of his hand. This became a part of my teaching routine—he would stretch his hand out to me and I would trace the graphs and shapes on his palm.

Teaching someone who is blind made me reassess my own teaching methodologies; I unlearned what I thought was the right way of teaching and learned better ways. And, I reevaluated my teaching methods, often while I was teaching. My student was my textbook— through his reaction and the overall level of understanding he derived from my lessons, I would assess my own teaching performance.

My experience with this student has made me realize that while his disability was visible to me, there are many more students in my classroom who may have disabilities that are not as visible. We, as educators, have to re-assess our classrooms collectively to create an environment that can benefit all the students coming through our doors at the beginning of each academic year. In retrospect, I realize I was mistaken in thinking that I was not going to be able to teach a blind student, and that a visually impaired student could not be a part of a classroom in a mainstream public school. I realized that I could not create a truly inclusive classroom without ensuring that all my students have their way of learning accommodated within the classroom. My visually impaired student taught me to be flexible as an educator and to be more open-minded towards my own teaching methodologies. Instead of basing my teaching methodologies on academic “know-how,” I began to see the value of focusing on the unique needs of my students as tools to help adapt my pedagogical techniques to facilitate student engagement and learning. I developed a deeper understanding of how all my students need to have their way of learning accommodated in order to get optimal results.

While I realize that mainstreaming students with disabilities into public school classrooms is a process that needs a lot of work in terms of management and resource allocation, I do think that this is fundamental to education systems that serve the social good. It helps to create truly inclusive classrooms. It provides beneficial learning outcomes for all students, and it is an incredibly enriching experience for their teachers as well. This experience made me turn my focus to a new dimension, where I see the needs of my students as opportunity for effective teaching and learning.

My personal experience has certainly opened my eyes to the potential benefits of having students with varied abilities within my classroom in the future, and I have my first visually impaired student to thank for that.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ayesha Anwar

Ayesha Anwar is a high school math teacher, currently working in Montreal. She has been teaching for eight years having worked overseas in an IB school. She is presently pursuing her Masters in Education and Society at McGill University, with a focus on science and mathematics.

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Fall 2021 issue.