Can Write: Meeting Canadian Writers and Illustrators of Children’s Books

What inspires the writers of the books your students read? How does an illustrator decide what to draw? Is it true that most authors and illustrators don’t know each other? This column features a different Canadian children’s book creator in each issue and shows you the story beyond the covers.

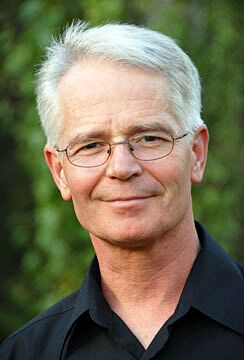

Books about dinosaurs, innovations and technologies. Titles like At The Edge and Life and Death. Who is Canadian author Larry Verstraete and how does he write such interesting, award-winning books?

Books about dinosaurs, innovations and technologies. Titles like At The Edge and Life and Death. Who is Canadian author Larry Verstraete and how does he write such interesting, award-winning books?

Margriet: Your topics and titles really appeal to kids. They are listed in the Canadian Children’s Book Centre’s Best Books. As a kid, did you love reading? And writing?

Larry: Books were among my best friends when I was growing up—novels, short stories, bios, non-fiction (science and history, especially). My brother and I had shared custody of stacks of comic books. We both enjoyed the sarcastic humour of MAD magazine. As for writing, I don’t recall willingly lifting a pen to draft a story on my own. The only writing I did was for school assignments, and those were returned with generous amounts of red ink. A career as a writer was not on my radar back then.

Margriet: You had a career as a teacher. How did writing become a new career?

Larry: Call it a fluke. After a long teaching day, I stopped for a haircut on the way home. The place was busy and while I waited for my turn, I thumbed through a magazine. One page stood out—an ad for a correspondence writing course titled “We’re looking for people to write books for children.”

To this day, I don’t know why I was so intrigued by the ad. Perhaps because I had been such an enthusiastic reader my whole life. Perhaps because I taught children and had two young kids of my own. Perhaps because I love the bond between readers who share books and wanted to create something that would have the same results.

I suspect it was all of these. I decided to give it a go, and, as they say, the rest is history. While I worked on course assignments, I discovered a story about a freak accident that led to a breakthrough in science. I wrote the story for the course but was so hooked on the topic that I continued to research and write other stories like it as I worked through the rest of the assignments. By the end of the course, I had a collection of stories around that theme.

The manuscript eventually found a home with Scholastic Canada and was published as The Serendipity Effect. By then I was bitten by the writing bug, and 30 years later I am still at it.

Margriet: Do you have a preference for writing fiction or non- fiction?

Larry: When it comes to non-fiction, I see myself as a storyteller and not so much as a writer of facts. Telling a true story comes with constraints, but I know the outcome before I start and the events that lead up to it, so, in a sense, I have an outline before I start. With fiction, creation is in my hands which is refreshing but also daunting because there are so many possibilities in play.

I enjoy both. Fiction is a nice break from non-fiction and vice versa.

Margriet: How does your writing process work?

Larry: I pull ideas from many places. I keep a “futures box.” When I find an article, clipping or something that piques my interest, I cut it out or download, print it, and throw it in the box. Every few months, I rummage through the collection. By then, I’ve forgotten what’s in there so it’s a bit like opening a gift. I’m always amazed at how many ideas surface.

Some of the best ideas for new books come while I am writing something else. For instance, while I was writing Case Files: 40 Murders and Mysteries Solved by Science, I thought I would include a story about the Hindenburg and use it as an example of how science revealed how and why the fire started. I never used the story in Case Files, but when I read about Werner Franz, the cabin boy aboard the Hindenburg, and his narrow escape, I knew right away that I wanted to tell his story. Eventually, I did. Surviving the Hindenburg is the result.

For non-fiction, once I have an idea, I dive into research. I try to find everything that is connected to the topic. If I can’t come up with a fresh take on the subject, I move on to something else. If the subject looks viable, I write a few pages to develop the voice and approach I’d like to use. From there, I create a proposal complete with an outline and a few samples.

Margriet: Hindenburg! Dinosaurs! Survival stories! Death defying escapes! Is your “real” life as exciting as your books?

Larry: Not at all. Like most people, I’ve had a few cliff-hanging moments of my own, but nothing the calibre of the subjects I research and write about. As a kid, I was fascinated by stories of heroes and true adventure, so I am probably fulfilling some inner quest for excitement by writing about others who live on the edge.

Margriet: How did you first get published?

Larry: When I wrote The Serendipity Effect, my first book, I did not have a clue how to find a publisher. I sent the entire manuscript to a publisher only to wait six months to have it returned with a note saying “thanks, but no thanks.” After that, I changed my approach. Instead of shipping off the entire manuscript, I now develop a proposal, add a few sample chapters, and send it off to several publishers at the same time. One was Scholastic Canada. Lucky for me, they were interested.

I’ve been published by other publishers since then. It helps to have a list of published books to back up your credentials, but that’s only one of the factors involved. For non-fiction, you are trying to sell an idea or concept. You need to prove to publishers that you have something original and current to offer. Whether or not you’ve been published before doesn’t matter if you don’t have something intriguing to bring to the bargaining table. For fiction, regardless of your previous works, you still need to prove that the story you’ve written is good enough for publication.

Having an established relationship with an editor or publishing house helps, though. In a sense, you are a known quantity to them. I’ve had a couple of projects drop into my lap because someone in a publishing house thought I would be a match for an in-house project.

Margriet: What do you do during school visits?

Larry: One of my goals when visiting classrooms is to leave students as excited about writing and reading as I am. I share my backstory and bring props, gadgets, posters, illustrations and other gear to make my session as interactive as possible. I tell stories, read passages, and use media to take students behind the scenes of writing and publishing so they can see how ideas eventually become the books they read.

Larry: One of my goals when visiting classrooms is to leave students as excited about writing and reading as I am. I share my backstory and bring props, gadgets, posters, illustrations and other gear to make my session as interactive as possible. I tell stories, read passages, and use media to take students behind the scenes of writing and publishing so they can see how ideas eventually become the books they read.

Margriet: What are you working on now?

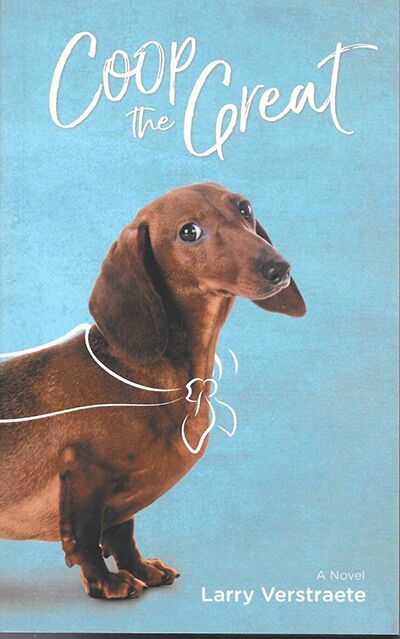

Larry: My last novel (Coop the Great) was a fictional story about a dachshund who is on a quest to find meaning in his life. The dog tells the story, and his voice was so fresh and vivid to me, that I had trouble leaving it behind. At this point, I am chipping away at a middle-grade novel that is very different from Coop, and I am happy to say that the pieces are beginning to come together.

For more information about this Canadian author: larryverstraete.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Margriet Ruurs

Margriet Ruurs is the author of 40 books for children, including her latest title Robert Bateman, The Boy Who painted Nature (Orca Book Publishers) MARGRIETRUURS.COM

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2020 issue.