Looking at school and district websites across Canada, most seem to have one thing in common: a statement referencing student goals in the areas of literacy, numeracy, and social-emotional learning (humane/character education). Twenty years ago, the latter goal was rarely seen, except perhaps in religiously based schools. However, as Nikolajeva (2013) points out, “like all other literacies, emotional literacy can be enhanced and trained, and here the teachers’ role becomes decisive” (p. 254).

The use of good literature to promote social-emotional learning in young people is well referenced (Wolk, 2009; Almerico, 2014). As Hall (2000) notes: “Stories engage our sentiments and make us feel deeply about people. Use of literature makes perfect sense to help children foster the ability to imaginatively reach beyond self” (p. vii). Picture books, specifically, have many advantages for the fostering of empathy in children of all ages (Nikolajeva, 2013; Costello &Kolodziej, 2006). Crawford (2014) notes that:

Picture books provide a particularly effective medium for learning life lessons. Because the plot unfolds and resolves quickly, they can serve as the equivalent of ‘case studies’ for young children who are learning to tease out important lessons about thinking and acting in a compassionate manner… With support, guidance and opportunities for meaningful language-rich literacy encounters, children can also have the potential to learn the habits of mind and tangible actions that will help them to act kindly and compassionately in their world. (pg. 171)

The Alberta SPCA’s AnimalTales program is but one excellent example of picture book based materials that have a positive effect on social-emotional growth. The program includes four books per grade, K–6 (free in Alberta), with accompanying manuals full of engaging, student-tested, cross-curricular activities. The books all use animals as their focus, with the goal of increasing respect and compassion for animals, people and the environment. Although there is some discussion in the research as to whether human or anthropomorphic characters are better conduits for teaching moral lessons (Larson, Lee & Ganea, 2017; Thompson & Gullone, 2003) there is no question that animals are intrinsically of interest to young readers.

Animals can often capture children’s attention, imagination and emotions in ways that people-focused subject matter cannot. Teaching abstract concepts like character and compassion can be easier, more engaging, and more fun when animals are the springboard for discussion. (Arkow, 2010, pg. 473)

During an independent program review that I conducted (Crawford, 2018), I found that in addition to ties to social-emotional learning, links to math, health, science, religion, art, and language arts curricula were reported by teachers in 18 classrooms (grades 2 and 5) across Alberta, increasing their interest in using the materials. The same ties would be applicable to other provincial programs of study.

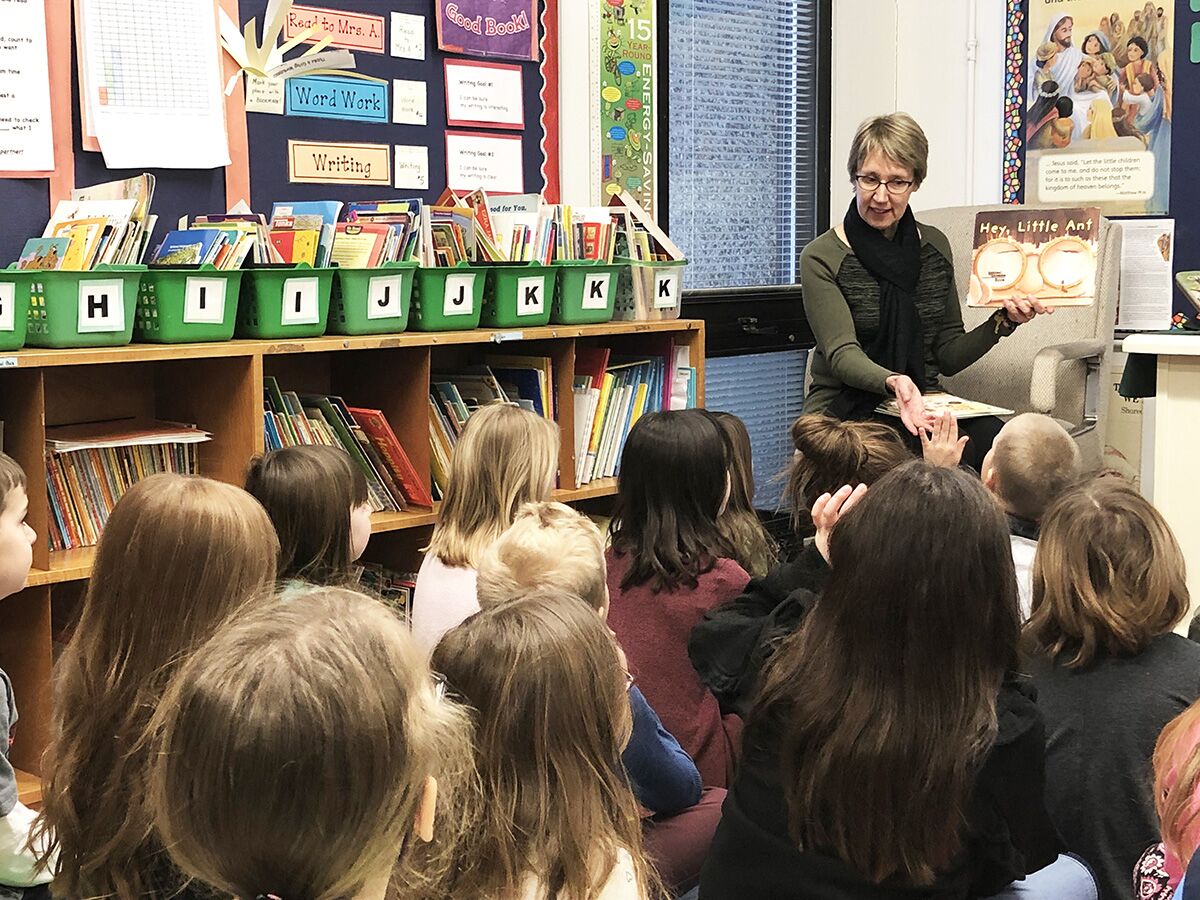

Mrs. Dolores Andressen, from St. Albert, Alberta reading Hey, Little Ant to her Grade 2 and 3 students.

Picture books allow teachers to discuss content ranging from grief to bullying to animal/human needs in ways that are comfortable and non-threatening for students. Not only is there need for presenting this kind of content with all students, but the majority of the classrooms I observed using picture books also had significant numbers of students with specialized needs, living in poverty, from refugee backgrounds, with limited English skills, or combinations thereof. One rural teacher noted: “This class has some severe behaviours, and I think picture books really helped them to see they need to take care of everything: small, large, everything has a purpose.”

Students in both grades were easily able to talk with me about kindness and caring. They could clearly identify times when they had been kind, when someone had been kind to them, when they had been unkind or had been treated poorly, and how kindness applied to animals.

Being kind is really important, because if you are not kind, then there is a ripple. If you are kind to someone, they will pass it on to someone else, and it will just keep going, and it can spread kindness all over the world. (rural, male, grade 5)

Students were also happy to comment on favourite books, new knowledge gained, or classroom activities they enjoyed that had been spurred on by the reading.

We looked up words like hospice. I got a really in-depth answer because you learn so much…one fact takes you to a million other facts. Most people found something they did not know. (rural, male, grade 5)

We wrote a story from the point of view of a human or an animal. You had to show empathy for the animal. I wrote from a wolf, I really like them and so does my mom. I know their habitat and what they do. (female, urban student, grade 5)

Because we read together as a class and we get into partners and we talk about the books, it just helps us to find a way to not be rude to each other, even when we have partners we don’t really like. That will help us better to be friends. (male, rural student, grade 5)

Teachers, students, administrators and parents all found AnimalTales in particular to be a positive experience. Teachers and students had other picture books they shared with me because they enjoyed reading and using them in the classroom; a sample of titles and their focus are noted after the references below. All participants recommended continuing the use of picture books in general, and AnimalTales in particular, viewing the books and activities as engaging and supportive of family and school goals and values.

Having picture books with animals as the focus helps the kids transfer the concept of kindness back and forth between animals and people, we can focus on treating all living things with kindness and how you treat animals how you treat others, treat others as you want to be treated. (metro teacher)

Our best class was when we compared ants and people and came to the conclusion that the more we know about something or someone, the more we understand them and have feelings for them. We extended that to people we meet in our classes from other schools or countries. If we know them we will be able to understand them and have empathy for them. (urban teacher)

Interest in picture books and the content seemed to be ongoing: “Even after we did the lessons, I heard them discussing the book in conversation, and kids would ask if we had books by the author or books like those” (rural teacher). For those teachers, schools or districts who are looking to encourage compassion while achieving a variety of curricular outcomes through the use of picture books, the everylivingthing.ca website and AnimalTales are worth a look. As one wise urban teacher noted, “ just knowing your math, as good as it is, if you are not a kind person, it might not get you very far.”

References

Alberta SPCA. (n.d.). AnimalTales. Retrieved from everylivingthing.ca

Almerico, Gino. (2014). Building character through literacy with children’s literature. Research in Higher Education. Vol. 26, October.

Arkow, Phil. (2010). Animal-assisted interventions and humane education: Opportunities for a more targeted focus. In Fine, Aubrey (Ed.), Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy. New York: Academic Press.

Costello, Bill & Kolodziej, N. J. (2006). A middle school teacher’s guide for selecting picture books. Middle School Journal Sept 2006, Vol. 38, Number 1, pp 27-33. Retrieved from www.nmsa.org/Publications/MiddleSchoolJournal/Articles/September2006

Crawford, Donna. (2018). Building compassion through picture books: How grade 2 and 5 students and teachers experience the AnimalTales book program. Retrieved from http://everylivingthing.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/AnimalTales-external-report.pdf

Crawford, Patricia. (2014). Beyond words: Using language and literature to teach compassion for others. In Jalongo, M. R. (Ed.), Teaching compassion: Humane Education in Early Childhood. pp 161-173

Hall, Susan. (2000). Using picture books to teach character education. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

Larson, N.E.; Lee, Kang; & Ganea, Patricia. (2017). Do storybooks with anthropomorphized animal characters promote prosocial behaviours in young children? Developmental Science. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12950

Nikolajeva, Maria. (2013). Picture books and emotional literacy. The Reading Teacher, Vol. 67, Issue 4, pp. 249-254. Retrieved from www.reading.org

Palacio, R. J. (2017). Peace, love and understanding. New York Times Book Review, August 27, 2017.

Thompson, K.L. & Gullone, E. (2003). Promotion of empathy and prosocial behaviour in children through humane education. Australian Psychologist, Vol.38, November 3, pp. 175-182.

Wolk, Steven. (2009). Reading for the world. Educational Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/jul09/vol66/num10/Reading-for-the-World.aspx

Picture Books additional to those used in Animal Tales

Bansch, Helga. (2009). I Want A Dog. NorthSouth: New York.

Clark, Emma. (2016). Plenty of Love to Go Around. Nancy Paulson Books: New York. (jealously and friendship/cat and dogs)

Day, Joy Morgan. (2007). Agate: What good is a moose? Lake Superior Port Cities: Duluth, Minn. (self esteem)

Graham, Bob. (2008). How To Heal a Broken Wing. Candlewick Press: Cambridge, Mass. (mostly pictorial, focus on caring)

Gravett, Emily. (2016). Tidy. Simon and Schuster: New York. (habitats)

Jeffers, Oliver. (2012). This Moose Belongs To Me. Harper Collins: London. (trials and tribulations of being a pet/owner)

Jones, Val. (2015). Who Wants Broccoli? Harper: New York. (pet adoption)

Kensky, Jessica. (2018). Rescue and Jessica. Candlewick Press: Sommerville, Mass. (disability/ability and animals)

Laminack, Lester. (2011). Three Hens and a Peacock. Scholastic: New York (farm life, individual worth)

McElligott, Matthew. (2009). The Lion’s Share. Walker and Company: New York. (equal is not always fair)

Macomber, D.& Carney, M.L. (2012). The Yippy Yappy Yorkie in the Green Doggie Sweater. Harper Collins: New York. (moving, dog helps make the change)

Marino, Gianna. (2017). Splotch. Viking: New York. (mom tries to cover up the death of a goldfish)

McAnulty, Stacy. (2016). Excellent Ed. Knopf: New York. (belonging, personal strengths)

Meisel, Paul. (2017). My Awesome Summer by P. Mantis. Holiday House: New York. (life cycle of an insect, diary form, nice picture, and funny…other than eating his brother and sisters)

Orloff, Karen. (2004). I Wanna Iguana. Putnam: New York.

Patent, Dorothy. (2002). Dogs on Duty. Scholastic: New York. (service animals)

Payne, Tony & Jan. (2003). The Hippo-Not-A Mus. Scholastic: New York. (being yourself)

Petty, Dev. (2015). I Want to Be a Frog. Doubleday: New York.

Prins, Ingrid. (2017). I Don’t Want a Rabbit. Clavis: New York. death of a pet)

Swerts, A. & Van Lindenhuizen, E. (2015). Dreaming of Mocha. Clavis: New York.(wanting a pet)

Voake, Charlotte. (2014). Melissa’s Octopus and Other Unsuitable Pets. Candlewick Press: Somerville, Mass. (suitable and unsuitable pets)

Wahl, Phoebe. (2015). Sonya’s Chickens. Tundra: Toronto. (death on a farm, cycle of life)

Walsh, Barbara. (2011). Sammy in the Sky. Candlewick Press: Somerville, Mass. (death of a pet)

Wheeler, Lisa. (2013). The Pet Project. Atheneum: New York (picking a pet, researching, using humour and rhyme, grade 5/6)

Williams, Mo. (2010). City Dog, Country Frog. Hyperion: New York (friendship, cycle of life, seasons)

Willis, J.& Reynolds, A. (2015). Elephants Can’t Jump. Anderson Press: Minneapolis, Minn. (unique talents)

For information regarding AnimalTales, contact Melissa Logan, Director of Education at the Alberta SPCA. mlogan@albertaspca.org

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Donna Crawford

Dr. Donna Crawford is a long-time teacher and administrator, currently working as a researcher for public and non-profit organizations. She is focussed on effective ways to enhance social-emotional learning in classrooms and public school alternative programs. She also supervises intern teachers from the University of Lethbridge.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Spring 2019 issue.