In conversation with colleagues, we all agree: teenagers are experiencing a mental health crisis of epidemic proportions. Their battle may be silent, but troubling statistics are becoming too loud to ignore. As teachers, we’re present to the rising number of students dealing with anxiety, depression, eating disorders and self-harm. And we don’t always know what to do about it. The rising tension is palpable in and out of the classroom—a sense of powerlessness and unease lines the edges of conversation I overhear parents having at the SportsPlex and the grocery store.

Often our own anxieties fuel attempts to rescue and fix our kids, and, not surprisingly, the recipients of our best intentions recoil. Or maybe we have the opposite reaction. Finding ourselves in uncharted waters we dismiss and withdraw—ignoring, avoiding or minimizing the problem. Sometimes in my own classroom, I catch myself interpreting symptoms as laziness or defiance. In these instances, I see my students’ actions as a reflection of myself: a personal offence, demonstrative of my inability to control a classroom. I take teenagers’ behaviour personally, because it directly affects me and, sometimes, is directed at me. From that space, I try to discipline the surliness, inattention and irritability, instead of investigating what is beneath it. Roots are, by nature, hidden beneath the surface. So I manage what I can see, unfortunately blind to the fact that these behaviours are symptoms of dysfunction, not causes.

The poetry unit I designed for the students of my junior high Language Arts classroom was an attempt to re-imagine our dialogue about mental health. I wanted to bring awareness to the matrix of interacting variables that affect each and every one of us and the way we relate to ourselves, each other, and our environment. Though I unquestionably advocate for crisis services for teens in distress, I also believe strongly in addressing the problem upstream. Changing classroom culture is imperative if we are going to make a difference for students prior to the point of acute crisis. My vision was for a classroom working collaboratively towards freedom from reactionary discipline, bullying and stigma. I wanted a space where teenagers could engage each other openly in an exploration of their internal struggle, for the purposes of greater understanding, compassion and support.

The poetry unit I designed for the students of my junior high Language Arts classroom was an attempt to re-imagine our dialogue about mental health. I wanted to bring awareness to the matrix of interacting variables that affect each and every one of us and the way we relate to ourselves, each other, and our environment. Though I unquestionably advocate for crisis services for teens in distress, I also believe strongly in addressing the problem upstream. Changing classroom culture is imperative if we are going to make a difference for students prior to the point of acute crisis. My vision was for a classroom working collaboratively towards freedom from reactionary discipline, bullying and stigma. I wanted a space where teenagers could engage each other openly in an exploration of their internal struggle, for the purposes of greater understanding, compassion and support.

Poetry functions in many ways like a backdoor, giving adolescents the space to speak about aspects of their experience which otherwise remain buried. Poetic language provides the safety of allusion, when pain is too raw to name directly. Inviting creative expression is often cathartic in itself, and a poem can function like a guide, drawing us into ever-deeper layers of our own associations. Sometimes, as my students have repeatedly demonstrated with the poignant specificity of a well-chosen metaphor, the only way to truly describe an experience is through image and analogy.

Our poetry unit began with a discussion of fifteen topics for which I designed introductory paragraphs and questions to inspire further thought. Topics included anxiety as a mind-body response to perceived threat, self-harm as a testament to emotional pain and trauma, bullying as abuse, and suicide and addiction as symptoms of disconnection. We also talked about acceptance, emotional awareness, mindfulness, and our relationships to Self (self-concept, self-esteem, self-love, self-talk and self-care) and Other (acceptance over judgment, compassion and supportive friendships). Each student chose a topic and a partner and added depth to their inquiry by defining and familiarizing themselves with mental health terminology such as bipolar, self-injury, cortisol and depression.

Next, students analyzed poetry performed and recorded in both written and spoken-word form, including OCD by Neil Hilborn, Letter to Depression by Bharath Divakar, When the Fat Girl Gets Skinny by Blythe Blaird, and Explaining my Depression to my Mother by Sabrina Benaim. I also sent home a list of recommendations for further reading if they were interested, including a few of my favourites: Depression and Other Magic Tricks by Sabrina Benaim and Sad Birds Still Sing by Faraway.

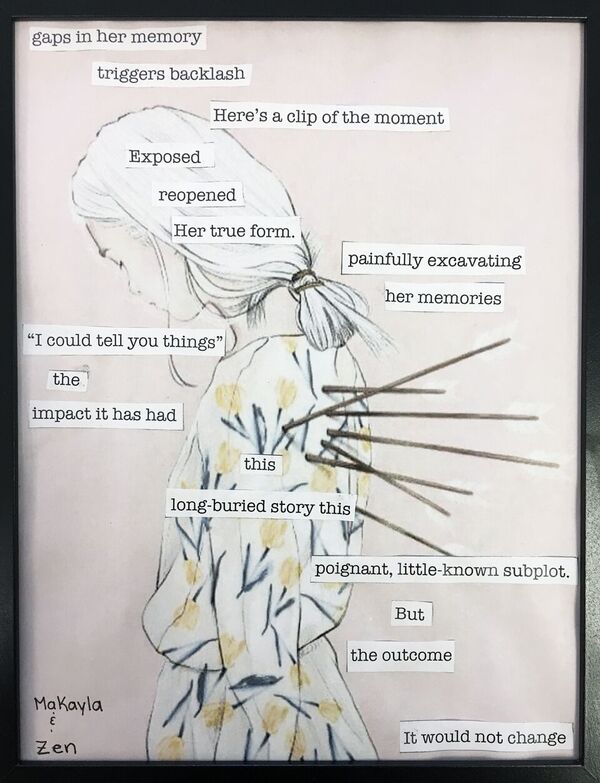

As a class, we discussed slam poetry as an art form, and the way it has been used by many who have felt marginalized, to mic their experiences. This was followed up by the documentary titled Louder than a Bomb to inspire kids in creating their own spoken word pieces. Next, we engaged in a found poetry activity which invited students to cut/paste words from an article discussing Trump, toxic masculinity, rape culture and the #metoo movement, and create a poem with the words they collaged. Below are some powerful lines that came from it.

I could tell you things/the/impact it has had/this long-buried story this/poignant, little-known subplot./But the outcome/It would not change. – Shame, by Makayla and Zen

How had she/become/interrogator of Self?/ personal/wrenching testimony/cavernous and cruel/credible only to/her – Self-talk by Mariana, Nathaniel and Daniel

We then invited Dr. Williams, associate professor and chair of the Humanities department at St. Mary’s University, to run a 3-hour poetry workshop for grade 8 and 9 students. (I strongly recommend reaching out to experts in the field, because they are often willing and eager to help!) For Dr. Williams, writing is a way of engaging critically and responsibly, with not only the world around us but also the one within us. She uses her passion for the written word to draw students into a deeper encounter with themselves and each other through projects which focus on poetry as pedagogy, feminism and intergenerational wisdom. She took what we knew about poetic form—what we were supposed to know, according to the mandates of provincial curriculum— and broke it open, expanding our imaginations about the possibility of poetic verse. She transcended the dusty must-dos of odes and sonnets, and nudged us to the edges of each line break, encouraging us to question the purpose of a pause. She also introduced us to Patrick Lane, as an example of a contemporary risk-taker who channels raw emotion to process his life experiences. Her presentation and presence left us empowered to analyze poetry with open hearts and critical minds.

Armed with all of this knowledge and momentum, student dyads worked together to craft a spoken word piece for performance. We all dressed in our finest attire and hosted a poetry café, performing pieces in front of a community audience comprising parents, grandparents, siblings and school staff members. Below are some of the comments from audience members.

Parent responses at the Poetry Café

I am so impressed with the incredible experience you provided for the students. Not to mention the great job the kids did in writing and performing. I wish all the junior high students in the city would be so lucky. Thanks for organizing such a special program. I feel it made a big difference in educating our kids (& parents) about mental health and in the process, starting to take away the stigma.

I just want to thank you. The kids blew me away. Such honesty and thoughtfulness.

I was so impressed with ALL of the kids and the level of dedication, creativity and gravitas that they brought to their performances. I’m sure that the experience will stay with them, as it will their parents, for years to come.

As teaching professionals, we are in a unique position to influence the conversation about mental health. We are front-line resources, first-hand witnesses, and helping professionals with keen insight into the student experience. We know deconstructing stigma and opening up spaces for conversation is a courageous and a necessary act, and yet many of us feel ill-equipped to provide psychotherapeutic support to teens facing the challenges of anxiety, depression, self-harm, bullying, stigma and more.

Poetry is one such access point to provide teenagers with an opportunity to process and integrate their emotions, find catharsis in self-expression, and discover a way to connect their personal suffering to the shared experiences of their peers. Our poetry unit invited us to query our narratives around mental health, open the floor for conversation about potentially taboo topics, expand our vocabulary, and add layers to our capacity for empathy. As evidenced by the samples above, poetry was our vehicle for imagining, visioning and challenging the societal scripts which mire mental health challenges in shame and stigma, and leave many teenagers to suffer in silence.

I am increasingly present to the reality of a formidable, generation-deep mental health stigma facing teenagers today. As a collective, we are starting to find ways to increase mental health awareness, and to dismantle some of the shame and silence perpetuated by stereotypes, but we still have much work to do. Bullying, fear of our own shadows, and age-old socio-cultural scripts perpetually bubble up in the microcosm of a junior high school. Though compassion, new language and emotional awareness would benefit many of our social spaces, the hallways and lunchrooms of middle schools are war zones desperately in need of armistice. Using poetry as a way to shift the conversation about mental health has completely transformed the way students relate to each other’s struggles, differences and pain in my classroom. Moving through this unit expanded our understanding of mental health from category to continuum and fostered a sense of shared experience, for the purposes of greater connection and compassion.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lesley Machon

Lesley Machon is a junior high school Language Arts teacher at the Calgary Jewish Academy. She devotes herself to the lifelong task of question-asking, querying assumptions, and empowering young minds to engage courageously with curiosity.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2019 issue.