Residential schools, genocide, terrorism—whenever issues like this came up, I used to feel at a loss, especially when teaching primary students. So I often swept the topics under the rug, counting on junior and intermediate teachers to broach the subjects later on. Then I discovered the power of inquiry based learning and, through this, realized that younger students are more than capable of reckoning with the difficult realities of our world.

This realization came to me as I planned a unit for my school’s official opening. The teachers were asked to explore a francophone country with their classes. I immediately thought of Corneille, a Francophone singer who lived through the Rwandan genocide. I knew Corneille’s story would touch my students but was unsure of how to introduce such a serious subject with them. A colleague suggested using inquiry which I soon realized was a powerful approach. Here’s what I learned about planning an inquiry unit and how it can be used to help students and teachers grapple with tough subjects.

1. Build on Existing Pedagogy

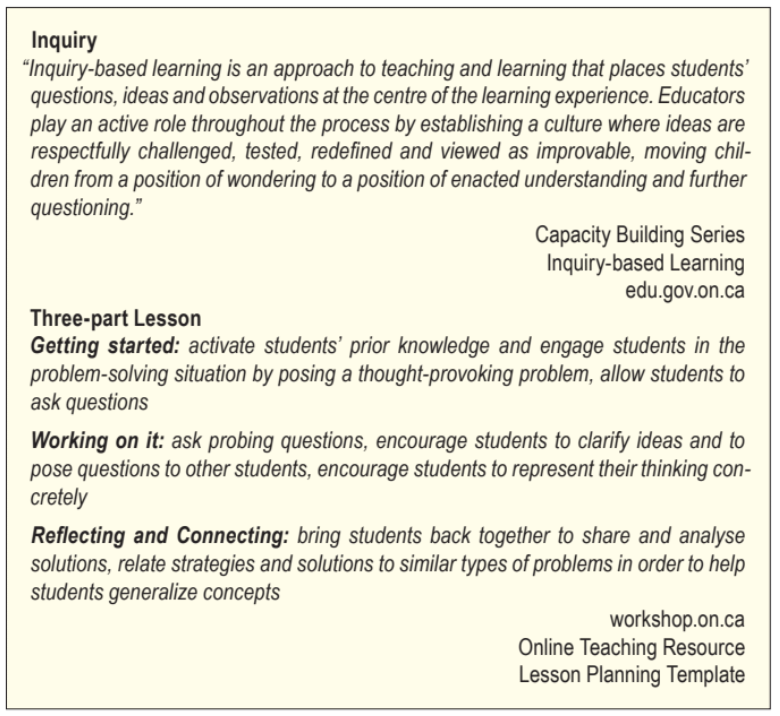

Using inquiry to broach difficult topics requires teachers to use a variety of teaching strategies. For example, three part lesson plans can act as templates for an inquiry project. When comparing the steps of a three part lesson with a description of inquiry, you can see that they work hand in hand.

I began the inquiry project with Corneille, the singer who grew up in Rwanda with his Hutu mother, Tutsi father and siblings. Corneille’s entire family was murdered in the genocide. He managed to escape and fled first to Europe then to Quebec where he has released four albums.

The first song I played for my class was “Seule au monde.” As we listened to the lyrics and watched the music video, I asked my students to imagine why Corneille was so sad.

Je marche droit pour ne pas plier

D’ailleurs, je chante souvent pour ne pas crier

Quand je pense à la vie

J’fais face à mes nuits

Chaque jour qui se lève me dit que…

Je suis seul au monde

I stand tall so I don’t bend

In fact, I often sing so I don’t scream

When I think about life

I confront my nights

Every new day tells me…

I’m alone in the world

Song: Je suis seul au monde

Album: Parcequ’on vient de loin

2002

After students discussed the song, I told them Corneille’s story and asked two questions:

1. How can we tell the story of Corneille in a way that visitors will remember?

2. If our school were Rwanda, how could we prevent violence?

From there, we moved forward with the “working on it” and “reflecting/connecting” elements of a three-part lesson.

My students decided to tell Corneille’s story with dramatic freeze frames (tableaux.) Their thoughts on the second question were displayed in a class book. At each point of the project, I used the three part lesson plan to help guide us. Because of this, I was much more comfortable forging ahead with inquiry and self-directed learning.

2. Start with Modeling

The importance of modeling became very clear to me from the beginning. At first, I had had the misconception that teachers shouldn’t be the ones creating the guiding questions. This isn’t true. Like any skill, inquiry needs to be modeled and there’s nothing wrong with teachers posing the initial questions, especially when students haven’t had exposure to self-directed learning. As my class progressed through our unit and saw examples of open-ended questions, students naturally came up with their own. There is a caveat to this. If students can’t relate issues to their own lives or to something concrete, they have a much harder time asking questions and reflecting on them.

The concrete aspect of our unit was Corneille’s story. My students understood the events in the genocide and their impact because they dramatised Corneille’s experiences. As they planned their tableaux, students started asking questions like: “What’s the difference between a person who is Tutsi and a person who is Hutu?” “Why did some Hutu not like Tutsi?” I encouraged my students to broaden the questions so they could make hypotheses. “How are people different?” “Why do people sometimes dislike each other?” Students shared ideas and then we discussed how to find answers (e.g., ask someone who comes from Rwanda, research the answers in a book or on a reliable Internet source, etc.).

The concrete aspect of our unit was Corneille’s story. My students understood the events in the genocide and their impact because they dramatised Corneille’s experiences. As they planned their tableaux, students started asking questions like: “What’s the difference between a person who is Tutsi and a person who is Hutu?” “Why did some Hutu not like Tutsi?” I encouraged my students to broaden the questions so they could make hypotheses. “How are people different?” “Why do people sometimes dislike each other?” Students shared ideas and then we discussed how to find answers (e.g., ask someone who comes from Rwanda, research the answers in a book or on a reliable Internet source, etc.).

To address the question of how violence in Rwanda could have been prevented, I made sure students could relate the experience to their own lives. This was done by having them imagine that our school was like Rwanda. The students’ ideas and questions flowed in an incredible way once they could put themselves in the shoes of Rwandans.

3. Be Ready to Adapt

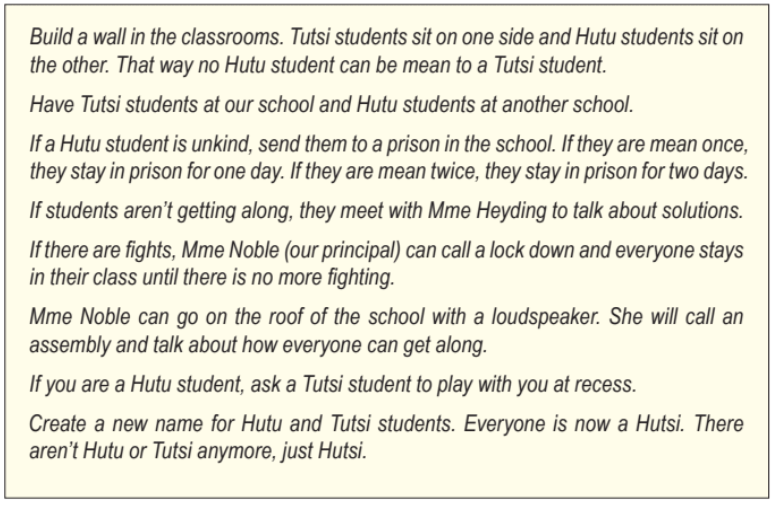

I usually plan units in a detailed way, knowing where we’re going and how we’re getting there. This can’t be done with inquiry projects. I realized this when my students started discussing the question: “If our school were Rwanda, how could we prevent violence?” Here are some of my students’ ideas:

The solutions were either shared through pictures or writing. For me, hearing about walls, segregation and lock downs was difficult and unexpected. I had nothing planned for how to help my students reflect on the humanity of their solutions. This is the reality of inquiry based learning; teachers have to be ready to think on their feet. I decided to use Corneille’s story again to help my students reflect on their ideas. “Which solutions would have made Corneille and his family the happiest?” I asked.Students placed the ideas into three categories:

A. Solutions Corneille’s family would have liked the best.

B. Solutions that have pros and cons.

C. Solutions that would have made Corneille’s family sad.

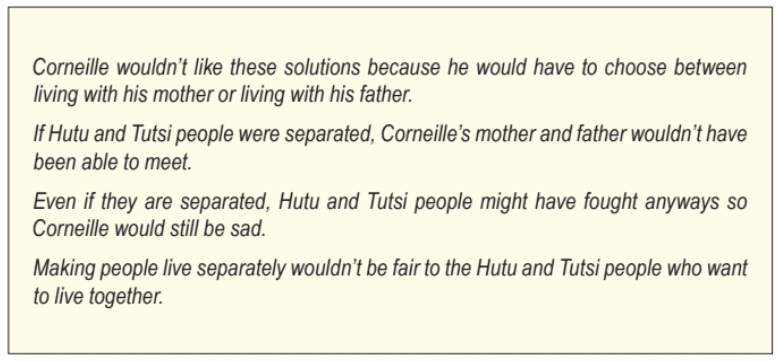

After discussing, each group of students ended up putting the “segregation” ideas (e.g., building walls, sending students to separate schools) into category “C.” These were their reasons.

To conclude the project, each student described and reflected on one solution (everything from kindness at recess to the building of walls to Hutu and Tutsi becoming Hutsi). Each reflection was included in a class book, which we shared with visitors on our school’s official opening night. The students did an amazing job of sharing Corneille’s story and explaining how we could prevent violence in the future. Parents also told me that their children were talking about Rwanda at home, showing them Corneille’s music videos and describing what they would do if our school had Tutsi and Hutu students. I attribute this to the fact that students had real stories to tell, real problems to solve and real questions that needed answering. It proves that, with the help of inquiry, primary students are ready to tackle our imperfect world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christina Heyding

Christina Heyding, B.Ed. (OISE), B.A. (McGill) is a Grade 1 French Immersion Teacher with the Durham District School Board in Ontario. She has taught with the Central Quebec School Board in Trois Rivières, La Tuque and Quebec City. Christina also has a post graduate degree in journalism at Concordia and has been published in The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Sept/Oct 2017, issue.