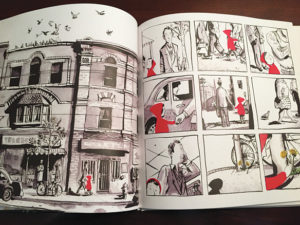

The wordless picture book is a unique genre of children’s literature in which stories are told entirely through illustrations. Unlike picture books that contain text, wordless literature relies exclusively on visual content to convey information to the reader. For emergent and more advanced readers alike, wordless books can serve as powerful motivational tools, as their openness to interpretation allows for limitless imaginative possibilities. Fortunately for educators, the past decade has seen a dramatic increase in the amount of wordless literature being published annually and there is now a plethora of books that teachers can choose from and implement in their classrooms (Arizpe, 2013). This publication surge has come in response to the demand for new multi-literacy instructional approaches as well as alternative, visually-driven resources that can assist children in enhancing their skills in visual literacy and verbal communication (Serafini, 2014). This article provides an overview of some of the main literacy skills that wordless literature promotes and offers strategies on how wordless books can be used to support learning and cognitive development in students at all grade levels, as well as with English Language Learners (ELLs).

The wordless picture book is a unique genre of children’s literature in which stories are told entirely through illustrations. Unlike picture books that contain text, wordless literature relies exclusively on visual content to convey information to the reader. For emergent and more advanced readers alike, wordless books can serve as powerful motivational tools, as their openness to interpretation allows for limitless imaginative possibilities. Fortunately for educators, the past decade has seen a dramatic increase in the amount of wordless literature being published annually and there is now a plethora of books that teachers can choose from and implement in their classrooms (Arizpe, 2013). This publication surge has come in response to the demand for new multi-literacy instructional approaches as well as alternative, visually-driven resources that can assist children in enhancing their skills in visual literacy and verbal communication (Serafini, 2014). This article provides an overview of some of the main literacy skills that wordless literature promotes and offers strategies on how wordless books can be used to support learning and cognitive development in students at all grade levels, as well as with English Language Learners (ELLs).

Research has consistently demonstrated that wordless books are beneficial tools in enhancing a wide variety of literacy skills. Findings of empirical studies have shown that narrative comprehension, or what is more commonly identified as awareness of the main conventions of stories including plot and character development, can become gradually more sophisticated over time after repeated interactions with wordless literature (Paris & Hoffman, 2004; Paris & Paris, 2003). For emergent readers, wordless books foster the development of fundamental narrative skills that will assist them when progressing to more complex picture books containing text. Wordless books also support advancement of verbal communication skills as they allow children to transform into active storytellers who orally share their interpretations of illustrations with peers (Jalongo, Dragich, Conrad, & Zhang, 2002). Since wordless literature is free from print, it actively promotes visual literacy by inspiring children to look closer and become perceptually aware of the visual information presented before them. Furthermore, wordless books can be especially useful resources for encouraging perspective taking (Lysaker & Miller, 2012). Without text to provide descriptions of what characters may be thinking or feeling, these books require children to remain mindful of facial expressions and to constantly be on the lookout for visual clues that could assist them in understanding portrayed emotions and experiences.

STRATEGIES FOR USING WORDLESS BOOKS IN THE CLASSROOM

Encourage Inquiry and Inference by Modelling

By explicitly modelling how to make sense of a book containing only illustrations, teachers will equip students with the skills necessary for interpreting wordless books independently. During a read aloud, teachers should frequently pose questions that require students to discuss what they are observing and subsequently reflect on how the observations contribute to their understanding of the content. Invite children to make ongoing predictions about what they believe will happen and how the main events in the plot will unfold. Teachers can also ask students to make inferences about character behaviours and actions and the roles they play in the outcome of the story.

Support Small Group Discussions

Exploring wordless literature in small groups allows students to collaborate in the analysis of illustrations. Children can take turns providing their own verbal interpretations of the entire story, or they can work together to generate a single team narration wherein a chain-like sequence of storytelling is created as each child provides a narrative to accompany one of the pages in the book. Invite students to discuss the similarities and differences between individual narrations as this will assist them in understanding how each person’s unique experiences and prior knowledge influence how the content of an illustration is perceived.

Use as Springboards for Creative Writing Activities

Wordless illustrations can serve as excellent inspirations for creative writing. Depending on grade level, students can write brief sentences or more detailed paragraphs to accompany single illustrations or the entire content of a wordless book.

Promote Attention to Detail

Since there is no text to provide clues about what is taking place in the illustrations, students will need to thoroughly examine the pictures and search for details that will assist in their comprehension of the plot. Teachers should actively model visual awareness by pointing to specific items and directing students’ gaze to specific areas of an illustration. Engaging in these actions will help students remain cognizant of the visual clues presented throughout the book and will also reinforce the importance of closely studying pictures to ensure that no important details are overlooked.

SUPPORTING LITERACY DEVELOPMENT IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

Locating instructional resources that effectively support the development of ELLs can be a challenging prospect, particularly when students are recent immigrants and possess a relatively limited knowledge of English. Wordless books can break down language barriers and encourage ELLs of all developmental levels to enhance their literacy skills (Arizpe, Colomer, & Martinez-Roldan, 2014). Some instructional strategies include:

Using Visual Content to Build Vocabulary

Placing sticky notes with word names next to specific components of the illustrations can help ELLs identify items and practise unfamiliar words. Illustrations can also inspire the development of weekly vocabulary lists and word walls.

Enhancing Verbal Communication Skills through Opportunities for Storytelling

Invite ELLs to frequently engage in verbal storytelling with peers. Since wordless books are open to individual interpretation, there truly are no incorrect ways to “read” the content. For many ELLs, this freedom can be quite empowering. With no print to decipher, motivation levels increase and students can instead focus on reading for meaning and developing their communication skills.

Introducing Students to Wordless Apps

Recently, the first wordless picture book apps have been made available for public and classroom use. The following is a brief synopsis of three wordless apps which are particularly beneficial for ELLs, but can also be used to enhance the literacy development of all students in the classroom:

- Imagistory allows students to choose and create their own wordless stories. A unique feature which is especially useful to ELLs is the voice record function which enables them to replay their narratives and share them with others. Allowing ELLs to listen to recordings of their own storytelling can be advantageous in helping them rehearse and revise their accounts to become richer and gradually more refined. imagistory.com.

- Spot is an interactive wordless app designed by Caldecott winning author/illustrator David Wiesner whose highly acclaimed wordless books include Tuesday, Free Fall, and Mr. Wuffles. Similar in nature to the concept of the wordless book Zoom by Istvan Banyai, Spot enables readers to literally “zoom in” and explore imaginative worlds up close. Not only is Spot valuable to ELLs for rehearsing oral storytelling, it can also serve as a creative source for weekly word lists. Encourage students to locate and identify new items in the imaginary worlds of adventure that they would like to incorporate in their lists. bitu.com/spot/.

- Little Story Maker is a user-friendly app which enables children to create simple visual narratives with photographs or other visual media. Once students are familiar with the genre, invite them to design their own wordless book. grasshopperapps.com/.

SUGGESTED WORDLESS BOOKS FOR CLASSROOM USE

Title – Author

Journey – Aaron Becker

Tuesday – David Weisner

Wave – Suzy Lee

Sidewalk Flowers – JonArno Lawson & Sydney Smith

Float – Daniel Miyares

Floatsam – David Wiesner

Flashlight – Lizi Boyd

The Girl and the Bicycle – Mark Pett

Unspoken – Henry Cole

Recommended for use with ELLs (due to simplistic storyline or references to immigrant experiences):

Here I Am – Patti Kim

Mirror – Jeannie Baker

The Arrival – Shaun Tan

Inside Outside – Lizi Boyd

A Ball for Daisy – Chris Raschka

Hank Finds an Egg – Rebecca Dudley

References

Arizpe, E. (2013). Meaning-making from wordless (or nearly wordless) picture books: What educational research experts and what readers have to say. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2), 163-176.

Arizpe, E., Colomer, T., & Martinez-Roldan, C. (2014). Visual journeys through wordless narratives. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Jalongo, M. R., Dragich, D., Conrad, N. K., & Zhang, A. (2002). Using wordless picture books to support emergent literacy. Early Childhood Journal, 29(3), 167-177.

Lysaker, J. T., & Miller, A. (2012). Engaging social imagination: The developmental work of wordless book reading. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 13(2), 147-174.

Paris, A. H., & Paris, S. G. (2003). Assessing narrative comprehension in young children. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(1), 36-76.

Paris, S. G., & Hoffman, J. V. (2004). Reading assessments in Kindergarten through third grade: Findings from the center for the improvement of early reading achievement. The Elementary School Journal, 105(2), 199-217.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christina Quintiliani

Christina Quintiliani is an Ontario Certified Teacher and Ph.D. Candidate at the Faculty of Education, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. Her doctoral research focuses on the role of wordless literature in children’s early literacy development. Christina has instructed at the elementary level and has become an advocate for visual literacy through her presentations at academic conferences and workshops for practising educators. Christina also serves as a reviewer of children’s literature for the e-journal Canadian Review of Materials (CM).

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Jan/Feb 2016 issue.