Befitting a rainforest environment, the sights and smells of the two Malaysian states we visited lingered in our mind’s eye, well after the trip ended.

Cruising down the Menanggol River.

Sarawak

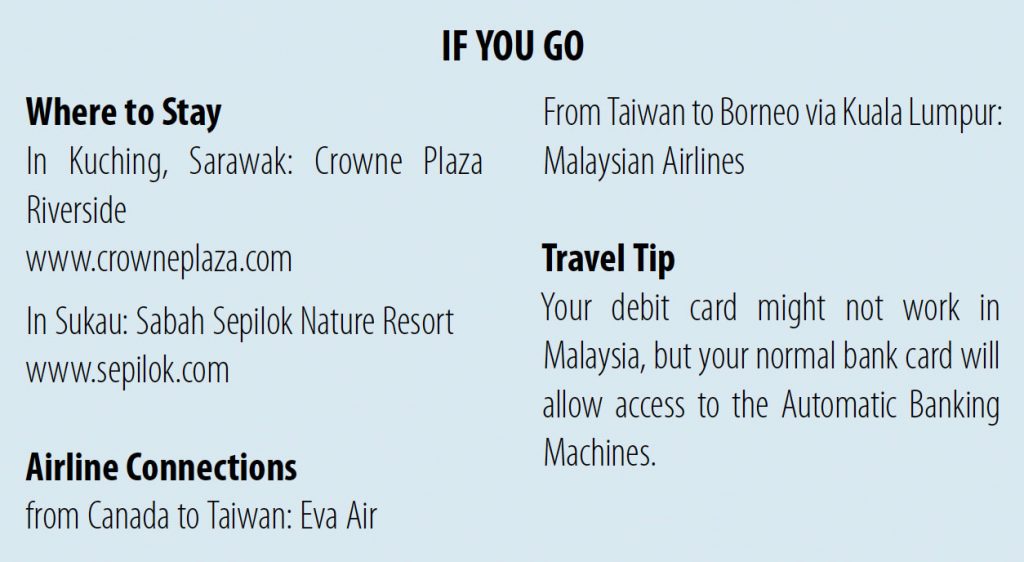

First stop was the southern Malaysian state of Sarawak, located in the mid-western pocket on the island of Borneo.

Visions of Borneo must be part of our subconscious mind, as after a short time there, Borneo’s Sarawak seems exotically familiar. That the whole area was a private fiefdom for three British rajahs, that headhunters practised their ways well into WW II, and that the eradication of piracy led to its becoming a modern state, all make perfect sense as one looks north over the Sarawak River at Kuching, the present-day capital. Perched in a hotel room above Gambir Road, the main street, the view is fascinating. Mount Santubong broods mysteriously to the left. At our feet is the turn of the Sarawak River where Sir James Brooke, the first white rajah, parked his private gunboat, forcing the Sultanate of Brunei’s lackey to cede part of his sultanate to Brooke. And in between the foreground and the background of this vision, the teeming rainforest. One square kilometre of Sarawak’s rainforest contains more tree species than the whole of Europe or North America.

Boarding boat to cross Sarawak River in Kuching, Malaysia.

Music lovers now flock to Kuching every July for the Sarawak Rainforest World Music Festival. The festival’s goal is to preserve and encourage native music from across the globe in a locale that is probably unique in the world of music festivals. Located right in the rainforest, next to towering trees and in a living museum that showcases the indigenous longhouses of the former headhunting tribes of western Borneo, the festival has become a draw for Malaysians and non-Malaysians alike.

Sarawak Rainforest World Music Festival.

But for us, the first Malaysian adventure is a visit to the Semenggoh Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre. The eerie shrill of the early morning cicadas, creating natural rainforest music, assaults us as we arrive at the orangutan sanctuary just forty minutes from Kuching. Adding to the excitement is the fact that meeting an orangutan outside of a zoo is not an easy thing to do. In the wild, they spend their time high in the trees, and spottings are usually limited to a glimpse as they build sleeping nests in incredibly high dipterocarpus trees. At the sanctuary, orphaned or injured orangutan are nursed back to health with the expressed goal of returning them to the wild.

As we approach one of the main feeding platforms, the suspense heightens as the overriding shrills of the cicadas egg us on. It is as humid as hell, even fogging our camera lens. On a bridge, we see a mother with her baby. We stop to gape and lose our guide. By the time we make it to the feeding platform, the orangutan start their antics, swinging from impossible angles using all four hands perfectly, climbing and descending trees. They look like they’re having a ball. Then they stop and look at us with a calm, reflective air.

We have to keep in mind that the ones we are watching shouldn’t be here. This is merely a transition stage for them. If the program works, you soon won’t see any of the orangutans who have managed to transfix three dozen international tourists. In the meantime, whenever you hear a crash of leaves above your head, you know one of them has arrived.

New strains and tones of cicadas reach us as we make our way through the jungle past columns of army ants and around towering trees and choking stranglers, back towards the bridge. We stop to view a huge, creeper-covered ironwood right out of Jack and the Beanstalk. Its exposed roots are like the toes of a giant Komodo dragon.

Suddenly we see a huge male orangutan. Because he is content to live the life of Riley and eat frequently at the sanctuary, he is as wide as he is tall, partly due to his overgrown coat. From the back, he looks like a comical robot from science fiction. Then another guide reminds us that a dominant male has the strength of five men and can rip your head off. We stop in our tracks. We frown, remembering that a smile and showing of teeth would be interpreted as a challenge. Who are we to challenge an ape?

Orangutan at Semenggoh Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre.

Sabah

In Sarawak’s sister state of Sabah on Borneo, natural wonders truly abound. On the Sea of Sulu, just across from the Philippines, the historic capital of Sandakan is the centre for excursions into the rainforest. A better choice is staying in a jungle lodge in the heart of the rainforest on the Kinabatangan River (Sabah’s longest river), to experience the jungle sights and sounds.

The lodge at Sukau serves as a place to eat and as a jetty for boat excursions. A good tour company will have you on the river as frequently as is possible from early morning mists to spectacular nightfalls.

Gliding in a small boat, with a motor designed to make as little noise as possible, the spectacle begins. More wildly intriguing cicada calls. Then the whoop whoops of a horn bill as it makes its way across a tributary of the Kinabatangan, the Menanggol. A rare green pigeon shoots across the bow of the dugout. The tiniest Borneo kingfisher, the blue-eared kingfisher observes us from a root in the riotous mishmash of root systems that make up the shore. Then he disappears in less than a flash.

The big boys start to make their appearance—male proboscis monkeys with huge bellies and enormous, long noses. The guide recognizes them from the way the distant tree branches begin to swing. Then we hear the rough roar, or so-called “long call” of a dominant male orangutan.

We continue along—intermediate egrets, like sentinels at almost every turn, signal the way to go. Then, a wild mournful call, truly out of this world. As if we needed further encouragement, we glide silently in the direction of this impromptu concert. It’s the gibbons monkey. Binoculars pop out. White-bellied sea eagles, Chinese egrets, estuarine crocodiles, purple herons and stork-billed kingfishers strut their stuff. Here, on the lower Kinabatangan wetlands, skirting through oxbow lakes and swamps, we encounter the largest concentration of wildlife in Malaysian Borneo.

The creatures we’ve missed seeing are as exotic as the ones we’ve seen. Sumatran rhinos, small wild Asian elephants, bearded pigs and spotted leopards have all been observed near the lodge, as photos by recent guests attest. Before we leave the lodge, a huge downpour occurs, the water cascading off the roofs of our cabins, making the rain gutters irrelevant. We can only image what the wet season must be like!

At a nearby village, we plant trees in a rainforest reforestation program with the chief of the local village. It pours for a moment then stops. The trees will provide the fruits that orangutans and proboscis feed on.

The chief sums up his paradise in a sentence, “Yes it’s peaceful here, no roads, no cars.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce Sach

This article is written by Bruce Sach.

Carole Jobin

The photos in this article are from Carole Jobin.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s September 2010 issue.