While planning a trip to Australia in early 2008, I realized that I would have two free days on my return trip, and for no extra cost could travel home via Beijing. I jumped at the chance to see this ancient city, if only briefly, in its pre-Olympics state. Think “China” today and you probably have images of cheap imports, massive industrial development and smog. It was not long ago, though, that your images would have been of Mao, the Great Wall and Tiananmen Square. How soon our perceptions change. Visiting Beijing presented all of those images and many more. What I found in this magnificent city of over eleven million inhabitants amazed, thrilled and comforted me.

Forbidden City Corner Tower and Moat

To appreciate foreign travel and truly understand a country and its culture, one has to set aside certain assumptions and values to. I believe this is true whether planning to visit Rio during the carnival or to see a bullfight in Spain. In many respects, the assaults to my sensibilities during my stop in Beijing were magnitudes less than what either of those may have been. Here I found friendly, inquisitive people from a cross-section of society living and prospering in a rapidly changing economic and political environment.

Traditional Siheyuan, or Courtyard Houses

The view from my hotel on the first morning provided the first real perspective on life in Beijing. From my window, I looked down on the clay tiled roofs of traditional siheyuan, or courtyard houses, that were formed by four single story or two-story buildings around a central open space, most marked by islands of trees. Past the labyrinth of alleyways that these homes created were built nondescript four and five-story blocks of brick apartment buildings and, just visible in the distance through the persistent smog, the pagoda rooflines of centuries-old garrisons, temples and homes. Below me in the street, a man straddled a contraption that appeared to have started life as a bicycle and on which he now transported a double bed that he had somehow lashed onto the back, passing several people in western style business attire and a parked Mercedes Benz as he rode slowly by.

Ornate gate at the Summer Palace

The hotel restaurant gave me another glimpse at the current state of the city. The language and accents of the patrons exposed them as German, American, French, English or eastern European. I did not see a single Chinese person in the restaurant other than the staff. Of the staff, there was the uniformity of dress, as could be expected anywhere in the world, and a definite spectrum in terms of their competency with English which, among the cosmopolitan clientele, was the common language. All the staff, mostly under about twenty-five years of age, tried hard to understand the varied forms of English spoken to them and when they were stumped by a word or request quickly referred to a more able person and then happily complied.

I always find that a telling element of the culture in any country is the way its people communicate with each other through the media. Mostly I enjoy television advertisements, no matter what the language, but newspapers are a pretty good indicator as well. In the west we all expect that China is a closed society and that the government controls the media so that the people hear only what the government wants them to hear. I was amazed, then, along with the ubiquitous flashy product promotions, to see and read a wide variety of domestic and foreign news, including updates on local crime, infectious disease outbreaks and social events, but also the travel by foreign leaders and world economic news. The news may have been censored—and certainly the television channel that was hosted by two young, uniformed military people had a definite political purpose and nationalistic theme—but it was difficult from a western perspective to determine what had been left out of the everyday news reports.

Traveling around the city I was also amazed at the number of Chinese tourists. I imagine that the new middle class is now affluent enough to be able to travel to see their historic sites that had until recently been inaccessible or perhaps even unknown to them. And they were like tourists anywhere, posing for photos in front of statues, reading the plaques and signs (many of which I was happy to find were also in English) and meandering annoyingly amid the local citizens and traffic.

Maybe the most interesting thing to my inquisitive mind, though, was that the streets of Beijing were absolutely spotless. There was not a candy wrapper, newspaper or fast food container to be seen anywhere. This was not due to an army of street cleaners, either. In fact, the absence of any municipal employees was noticeable—unless of course you include the army itself, which was evident in limited numbers at the Olympic construction sites and at all the historic sites. It may be that the public discipline expected of this society also includes a public respect for the city’s appearance.

Olympic Site

The varying textures of the landscape, buildings and people with every new area I visited were the most thrilling to me: the ancient sites in contrast with the new architecture, the modern lifestyles juxtaposed with the traditional. Take, for example, the Summer Palace. This expansive site is accessed from an eight lane highway (which, I will add, my taxi driver chose to reverse along when he missed the exit—an experience that will rank high on my “things not to do” list) that passes through a precinct of monotonous concrete residential towers. The access road passes a shanty town of rough dirt roads and the pungent smell of cooking oil where street sellers and guides for hire are everywhere among the small shade trees that surround the North Palace Gate. But once through the gate, the outside world is sacrificed to the splendor of this oriental treasure.

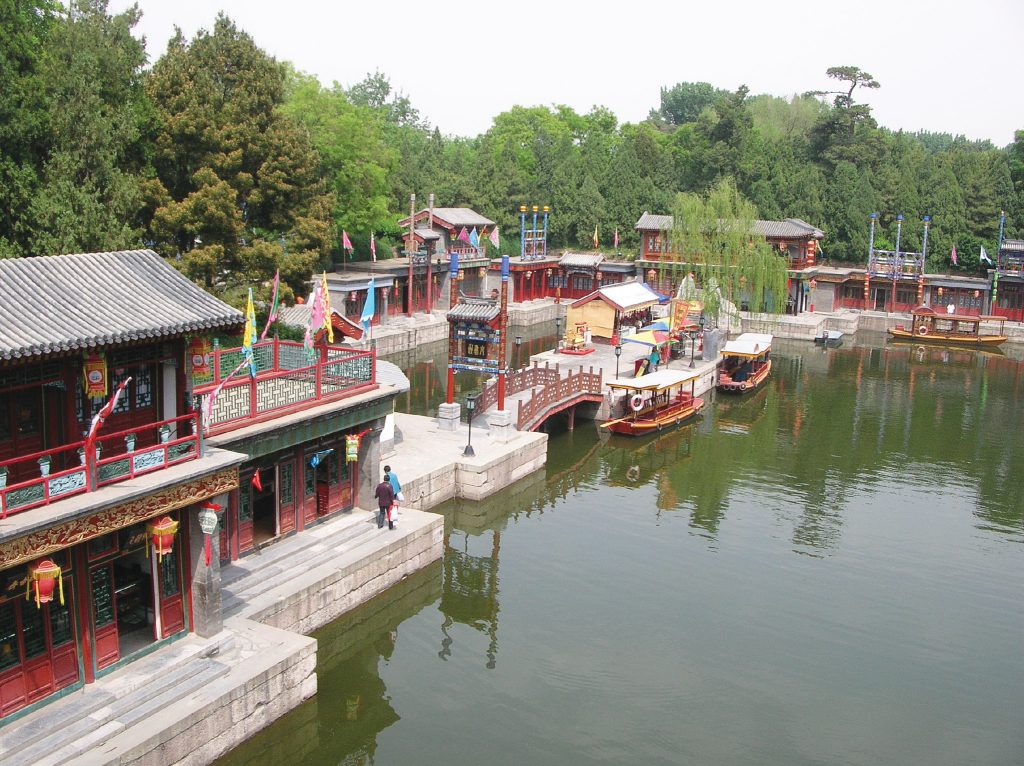

Here is Suzhou Street, a collection of shops first built in 1751 to imitate those along the canal in the city of Suzhou. Pathways run along both sides of this narrowing of the Back Lake, joined by elegantly arched bridges and lined with traditional shops selling delicate fans, richly coloured fabrics and folk art. Canopied barges ease passengers along the canal amid the calming music of stringed instruments as men and women in traditional dress serve guests at small waterside restaurants. It is a mystical setting that introduces the visitor to the intrigue of the Summer Palace, a 290-hectare collection of waterways and landscapes that holds palaces, temples and pavilions atop and around Longevity Hill. The grounds are adorned with bronze and stone sculptures and gardens shaded by ancient cypress and pine. It is a spectacular place that was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998.

Suzhou Street at the Summer Palace

Another example is The Forbidden City in the heart of Beijing, located just a short walk from Tiananmen Square. Built in 1420, it was the home of twenty-four successive Emperors for a total of 491 years until the Qing dynasty fell to republican revolutionaries in 1911. The pagoda style roofs of the grand halls and the guard towers at the four corners of this rectangular fortress are visible from the modern high rise towers of the nearby financial district. It is an impressive sight, measuring 961 metres long and 753 metres wide with walls of rammed earth and three layers of protective brick inside and out, standing over 8 metres wide at the base and almost 8 metres high and surrounded by a moat that is 6 metres deep and 52 metres wide. This amazing structure contains 980 buildings and now houses the Palace Museum with its over one and a half million artifacts dating back over 5000 years.

Organized groups of tourists in colour-coded attire and throngs of individuals, both Chinese and foreigners, were being delivered by tour bus, a never-ending fleet of taxis or powered rickshaws when I arrived. But inside this massive complex they seemed to disappear into the vast empty spaces of history so that it seldom felt crowded. Even the extensive refurbishing that was underway hardly detracted from the impressive scenes, like the incredible ceramics decorations, the massive gates and simple glazed brick parapets. Still, the digital video cameras and rambunctious children reminded me that I could be at almost any tourist site on the planet.

I was comforted by the freedom with which the Chinese people explored their own history and their appreciation of the incredible new architecture, and by the obvious pride that they displayed in their anticipation of the coming Olympics that would showcase their city and culture to the world. They demonstrated a fondness for their past, a progressive attitude of hope for their future and a genuine friendliness. I can’t wait to go back.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alan Boreham

Alan Boreham is a world traveler and co-author of two books—a series of South Pacific sailing memoirs entitled Beer In The Bilges and a novel entitled Two If By Sea. Blog: alanboreham.wordpress.com Web: 2ifbyseabook.com

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s September 2009 issue.