I teach junior high. The kids in my classroom prefer TikTok and Minecraft to novels. Keeping my students engaged in the humanities curriculum is not always easy, but there are a few things I have learned over the past decade that make it easier. I provide options, incorporate technology, and encourage collaboration. The most effective strategy, however, is leveraging the eminently human motivation toward meaning-making. This is what “relevant content” is all about because students want to sense that their studies matter. So, I choose topics I care about personally, and I lean into the edges of my discomfort as we explore them. This encourages students to follow suit by taking intellectual and emotional risks, asking better questions, and investing themselves in discovering the answers.

On that note… let’s talk about death.

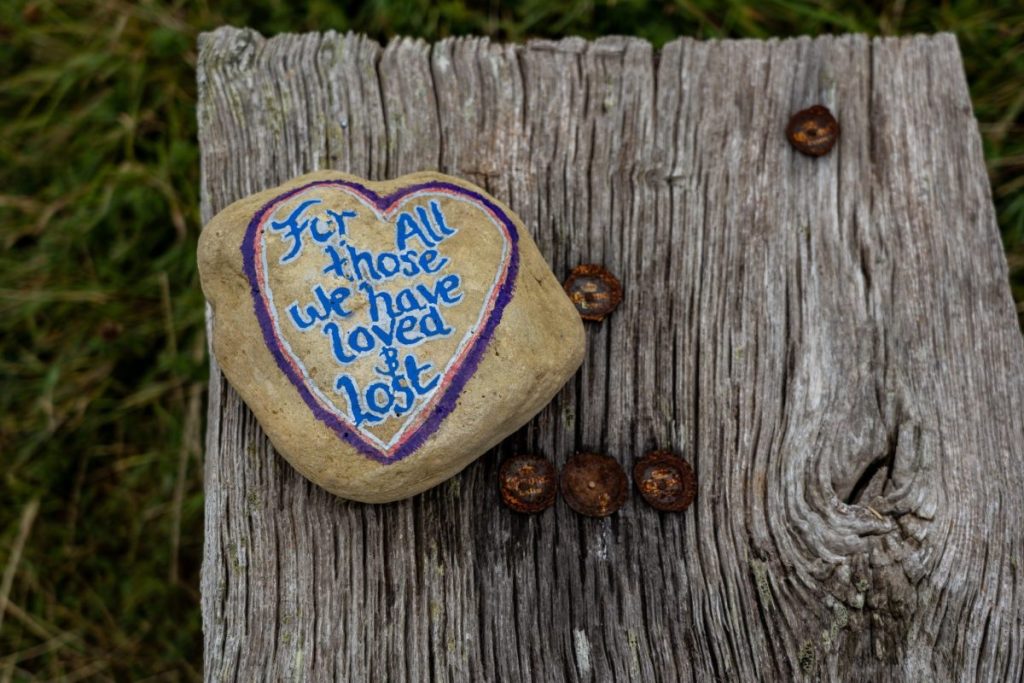

Our school community experienced some significant tragedies in recent years, and, in my desire to offer support, I committed to learning everything I could about the grieving process. This, despite some personal and societal death phobia and the fact that death is not a particularly dominant theme within our cultural conversation. I started reading Amanda Achtman’s blog “Dying to Meet You,” which is where my plunge into the depths of death work truly began. Over the course of her 365 daily posts on death and dying, my own perspectives began to shapeshift.

I began reading interviews about rites of passage and burial practices with Stephen Jenkinson (author of Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanity and Soul). Next, I discovered some of the lyrical prose of grief worker Francis Weller (author of The Wild Edge of Sorrow). As a literary enthusiast, I began wondering if our collective inability and unwillingness to talk about death was related to the language we had available to us in the Western world. I wondered too about how to die well since it seemed an inevitable threshold, and asked: what might dying well and living well have in common? I was insatiably curious about the impact that a different approach to death might have on our approaches to life.

I decided to pursue additional training in death work (death doula and thanatology certification, as well as grief and bereavement counselling), and now spend time at the local children’s hospital engaging with critically ill children. It’s an incredibly and undeniably rewarding experience. Walking this road has deepened my appreciation for life, and transformed the way I show up in the classroom. In this article, I will share why I think death is an important topic to explore with young people, and lay out my process in six steps, so you can explore death in your own classrooms, too.

Step One

First, I wrote a letter to students and their families before the beginning of the school year, framing our intention to explore death (within the many other topics we would cover) in the classroom and inviting follow-up questions from parents. I will include an excerpt to get you started:

This year our studies will connect us with suffering, compassion, and what it means to live—and die—with a sense of reverence and integrity. We will read short stories, true stories, and poetry about children experiencing illness, and also hear from guest speakers who experienced despair, healing, and deeply humbling vulnerability…

Sensitivity is crucial, keeping in mind the fact that many families have experienced great loss. I wanted to validate any hesitations and demonstrate that I am prepared to conduct our exploration with respect and compassion.

Step Two

I began the year by introducing a research project I created called “From Lab Coat to Sweatpants: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Empathy.” This assignment involved reading and researching a medical story. Each student chose a child with a specific diagnosis from a list of provided links. (I located the stories from open-access hospital databases.) The students explored each illness—first from a scientific perspective. Next, they engaged with the stories on an emotional level, considering their own thoughts and feelings as well as those of the child and the child’s family. They were also asked to search for representations of the diagnosis in the media and to create their own representation if none existed. Finally, they reflected on the impact of the assignment as well as the value of empathy in their personal lives and relationships.

Step Three

I wove the theme of death and dying into each subsequent unit: poetry, novel study, and film study. We read and analyzed poems such as “When Death Comes” by Mary Oliver, “When I Die” by Rumi, “When Great Trees Fall” by Maya Angelou, and “On Death” by Khalil Gibran. I chose the novel The Universe VS Alex Woods for a Grade 9 novel study. During film studies, we watched Me, Earl and the Dying Girl; Up; and A Monster Calls. Other possible resources include:

Personal Essays

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

The Long Goodbye by Meghan O’Rourke

Poems

“Death of a Young Son by Drowning” by Margaret Atwood

“The Dash” by Linda Ellis

“The Grief of Others” by John Burnside

Podcasts

Terrible, Thanks for Asking (episode: “Love and Death”)

The Moth (episode: “Death and the Compass”)

This American Life (episode: “In the Event of My Death”)

Step Four

Throughout the year, I invited various guest speakers to speak to our class, including a child who was only given 24 hours to live (but who lived to receive a rare transplant and was labelled a medical miracle) and her mom. Many medical families share their stories and educate the public through social media, and I reached out to a few parents who were excited about the invitation to present to our class. The students enjoyed this aspect immensely and asked insightful questions, such as what one mother felt when she was given the news of her daughter’s prognosis, and how she coped with the devastating news.

I also invited other guest speakers, including a rabbi, an Indigenous death doula, and Amanda Achtman, blog creator of DyingToMeetYou.ca and an expert in bioethics, to discuss end-of-life ethics from a humanizing and aspirational perspective. Guest speakers added valuable insights and diverse perspectives to our discussions.

Step Five

I typically include a service project in my classroom, so this year we crocheted hats and wove friendship bracelets for oncology patients at the Children’s Hospital and made art for the doorways of those admitted for a longer stay.

Other possible ideas could include:

1. Create and deliver care packages or gift baskets for hospital or hospice patients, including books, puzzles, blankets, and personal care items. Some units and cancer treatment centers keep updated lists of desired donation items, so reaching out to administration is often useful.

2. Write letters or create cards for patients to provide a sense of connection and support.

3. Organize a fundraiser to donate to a medical charity or hospital.

4. Volunteer at a hospital or hospice facility, assisting with tasks such as delivering meals or running errands. Alternatively, students might offer companionship or entertainment by reading to or playing games/cards with patients.

5. Create and lead a workshop or activity for patients, such as art or music sessions.

6. Offer to shovel sidewalks, wash cars, or do yard work for patients or their families to alleviate some of the challenges of caregiving.

7. Donate blood or sign up to become an organ donor to help save lives.

8. Raise awareness about a particular medical condition or disease by sharing information and resources with the community.

Step Six

I set aside one day of classroom time each week to devote to the theme, which includes anything I cannot necessarily fit into a set unit. Students either work on their service project, or sometimes we learn about a death custom in another country via podcast or film.

In conclusion, exploring death and grief in the classroom might sound dark, but it can be a valuable way for junior high students to engage with their studies and learn the art of compassionate inquiry. By providing structure and resources to scaffold this exploration, teachers can create a hospitable and engaging environment for students to contend with experiences with illness, death, and grief. These experiences cultivate maturity in students and prepare them to lead empathetic and responsible lives filled with meaning and compassion. As a teacher who has experienced the benefits of incorporating death education into the curriculum, it is clear that engaging with these difficult subjects can have a profound and positive impact on students’ personal and academic growth that contributes to satisfying their thirst for meaningful learning.

**All of the material I created can be found on my blog wildwoodwordsmiths.ca**

Lesley Machon

Lesley is a Canadian teacher who loves literature and cares deeply about living and dying with dignity and integrity. She strives to make classroom and curriculum content meaningful and braves the exploration of taboo topics by asking Life and Death-sized questions.

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2023 issue.