In our rapidly evolving and globalizing world, the literacies needed to absorb, share, transform, and create knowledge are diversifying. Teachers can help their students to succeed in school and society by developing their capacities to conceptualize and engage in multiliteracies.

What is “Multiliteracies?”

The term multiliteracies was first coined in 1996 by the New London Group to capture expanding notions of literacy and its connection to the changing social environment facing students and teachers (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000). Rather than merely thinking of literacy as the texts we read and the words that we speak, multiliteracies includes multimodalities, cultural diversity, technology, and an underlying commitment to social justice issues. Multimodalities are the combining of modes. For instance, students creating a rap song video might utilize dance (gestural mode), captions (linguistic mode), and singing (oral mode).

Research Study

The high school biology/English teacher discussed in this article is a participant in our national Canadian research study. Her work is featured on the web platform www.multiliteraciesproject.com. This web platform serves as a resource for our Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) research to help teachers understand and implement a multiliteracies pedagogy in their own classrooms. Its main components include original film footage of teaching in action; interviews with teachers, students, and adult educators; as well as sample lessons and educational resources. We hope to promote dialogue amongst teachers through The Multiliteracies Project.

Supporting Teachers

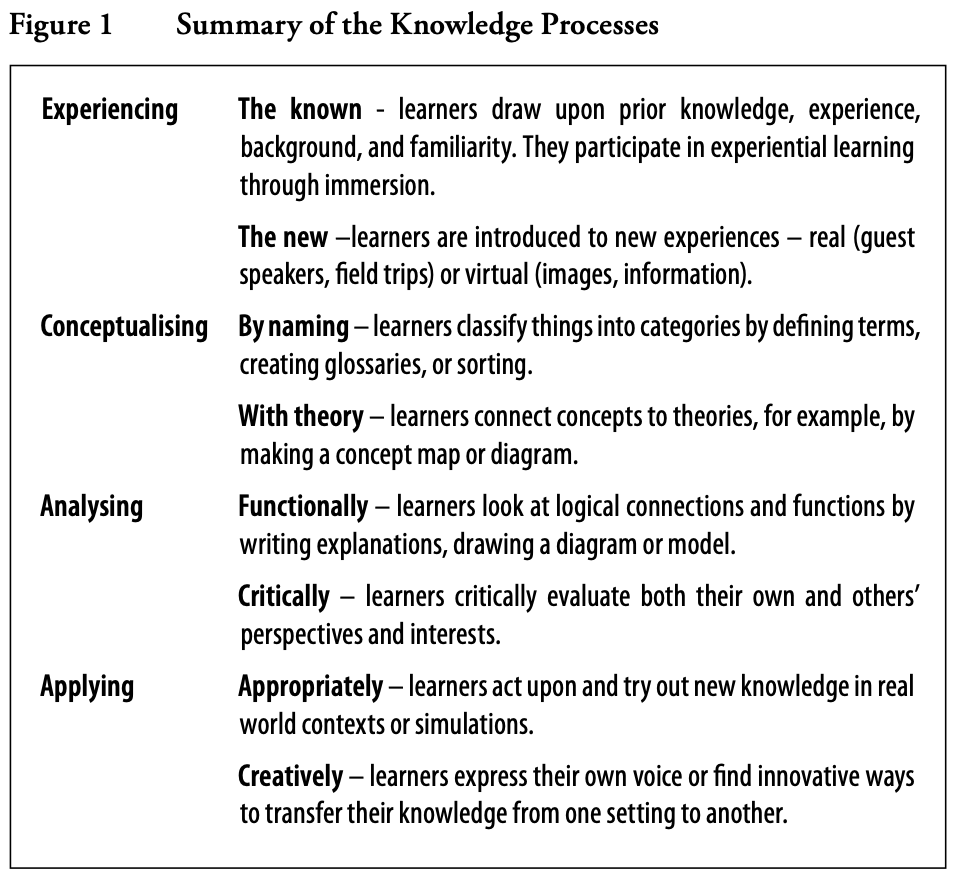

With literacy continually evolving, there remains a need to support teachers’ conceptions of multiliteracies. Kalantzis and Cope (2005) reframe four dimensions of pedagogy originally identified by the New London Group. These ideas were translated into more recognizable pedagogical acts for planning, documenting, and tracking learning called “knowledge processes” (Kalantzis & Cope, 2005). Figure 1 summarizes Kalantzis and Cope’s (2016) knowledge processes as a checklist of activity types to help give teachers and learners control over instructional choices and learning outcomes. Knowledge processes are not taught in any particular order. Instead, using a teacher’s professional judgement, the knowledge processes are teaching elements meant to deepen learning and enhance lesson designs.

With literacy continually evolving, there remains a need to support teachers’ conceptions of multiliteracies. Kalantzis and Cope (2005) reframe four dimensions of pedagogy originally identified by the New London Group. These ideas were translated into more recognizable pedagogical acts for planning, documenting, and tracking learning called “knowledge processes” (Kalantzis & Cope, 2005). Figure 1 summarizes Kalantzis and Cope’s (2016) knowledge processes as a checklist of activity types to help give teachers and learners control over instructional choices and learning outcomes. Knowledge processes are not taught in any particular order. Instead, using a teacher’s professional judgement, the knowledge processes are teaching elements meant to deepen learning and enhance lesson designs.

In Practice

The biology/English teacher, who is also a participant in our research study, created what is called a RAFT assignment that also connects to Kalantzis and Cope’s (2016) knowledge processes. This is a research assignment where students choose their Role, Audience, Format, and Topic (RAFT). In each of the four columns in the RAFT assignment instructions, students have many options to customize their RAFT. For example, a student might choose to role play as a doctor talking to her support group for patients who have been diagnosed with AIDS. The student has created a visual aid in the format of a comic book to bring these patients into a dialogue where they can use the narrative of the comic characters as a prompt to discuss their concerns without feeling the need to confess personal details of their own lives or experiences with the disease. Thus, the RAFT chosen by this student to explore microbes is Role: doctor; Audience: support group for patients; Format: comic book; Topic: AIDS. (Alternatively, the RAFT she might have chosen from the assignment columns could be Role: journalist; Audience: members of parliament; Format: newspaper article; Topic: Anthrax.)

In terms of Kalantzis and Cope’s (2016) knowledge processes, a student works with prior knowledge to select a topic of interest, in this example— AIDS—and chooses a role to immerse herself in—doctor (experiencing). The student researches the biological concept of microbes and understands the theory in relation to AIDS (conceptualising). She contextualizes the biology content in real world terms and gears it toward an audience—the patient support group (analysing). Finally, a student takes what she has learned and applies knowledge in a creative format such as a comic book in this example (applying).

As the teacher reflects on her students’ experiences, she notes that “I have found that this [RAFT assignment] is getting them to learn the most about their particular topic because they are invested in it.” A student using the RAFT has lots of choice in narrative. She is not only learning about microbes but also how biology impacts people’s lives in very real ways. The student also learns to think like a doctor by role playing with this specific audience in mind—questions of ethics, professional care, human rapport, institutional supports, accurate medical facts, and effective communication geared toward these patients all come into the complexity of creating an effective comic narrative. The comic is multimodal. It draws upon sketches, colour, shading (visual mode); speech bubbles, narrative, captions (linguistic mode); sound effects like “wham” (oral mode); and panels, gutters (spatial mode). Students who perhaps struggle with more traditional forms of scientific writing can communicate using the RAFT strategy based on their own strengths and interests, while still developing sophisticated scientific understanding and literacy skills. English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners in particular often benefit from these type of multiliteracies assignments. In terms of assessment and evaluation, the teacher observes that students enjoy that the assignment “is structured like how it is being marked. They know exactly what they need to include in it.”

This biology/English teacher also reinforces key concepts about microbes through mind maps that students create themselves. As the teacher states, the students use their class notes to create their mind maps as they choose to, and “they are pulling out the most important parts [of their class notes], and generally, it reflect[s] their success as well.” Thus, students learn to independently delineate which information is most important, deliberate how to visually represent abstract biological processes, and reinforce their own understanding of these key concepts.

Conclusion

A multiliteracies pedagogy allows teachers to reflect upon their students’ learning styles, focus on celebrating the background and prior knowledge of each student, and see the value in the process of differentiation. As teachers, we need to strive to help students build the capacity to engage critically with the complexities of the world’s communication systems.

References

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. Routledge.

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2016). Literacies pedagogy. In Literacies (pp. 67-83). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316442821.004

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2005). Learning by design. Victorian Schools Innovation Commission.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review,66(1), 60-93. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Susan M. Holloway

Susan M. Holloway is an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Windsor. Her research interests include literacy, multiliteracies, socio-cultural perspectives on language learning, adult education, teacher education, critical and feminist theory. She is the principal investigator on a current SSHRC grant that focuses on exploring multiliteracies theory in relation to adolescents and adults in the Canadian context.

Gelsea Pizzuto

Gelsea Pizzuto is a Ph.D. student in Educational Studies specializing in Cognition and Learning through the University of Windsor Joint Ph.D. program. She is a research assistant for The Multiliteracies Project SSHRC grant. Gelsea is also an elementary occasional teacher with Greater Essex County District School Board. Her research interests include alternative education, social and emotional learning, mental health amongst children and youth, and holistic education.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2021 issue.