When I travel, I know there are wonderful learning opportunities lurking everywhere. During a visit to Oahu, Hawaii, before the pandemic hit, I came across some wonderful projects that teachers will enjoy.

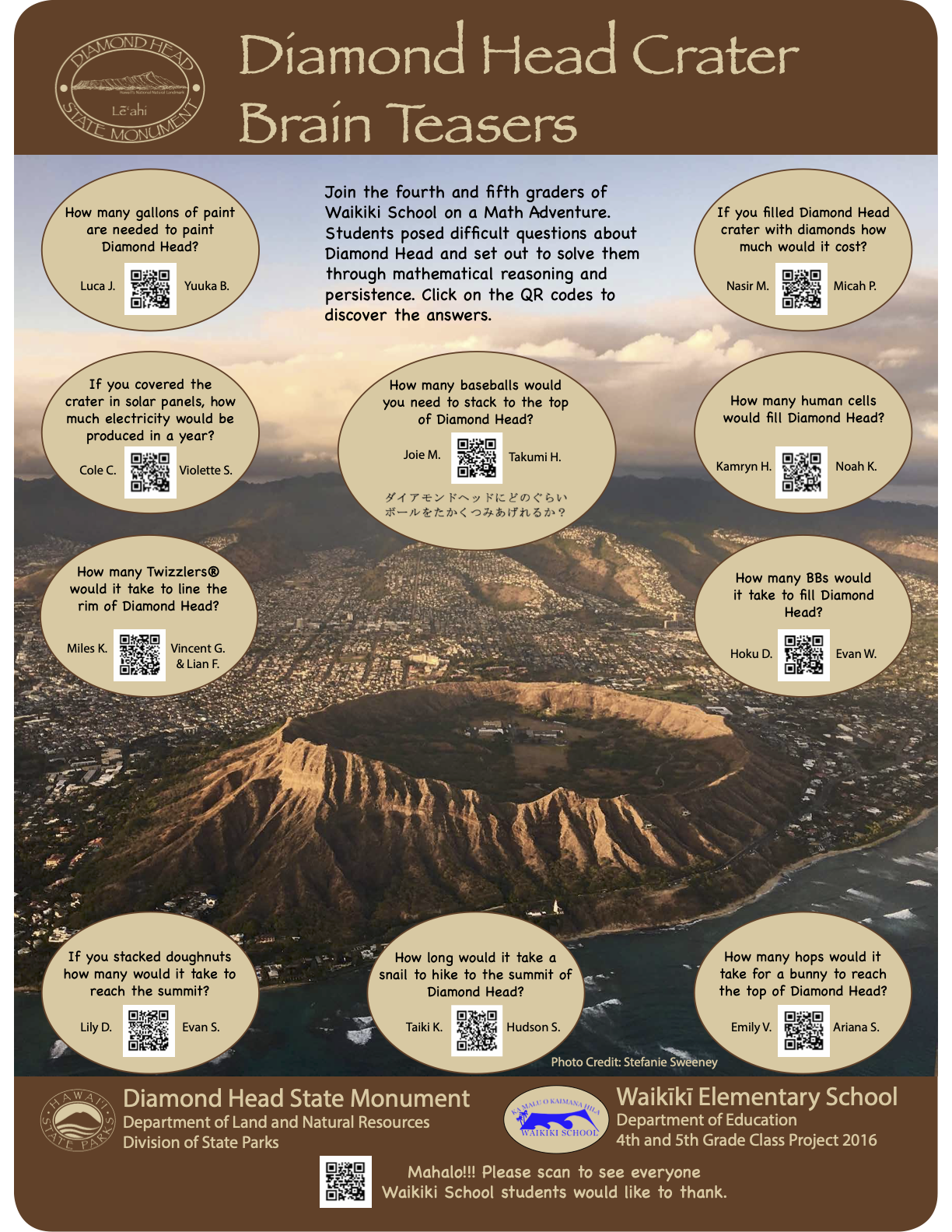

The sign I noticed was right at the trailhead and posed some unusual questions:

• If you covered the crater in solar panels, how much electricity would you produce in a year?

• How many Twizzlers would it take to line the edge of Diamond Head?”

Burning questions that could only originate from students having fun with science. I held my phone in front of the QR-codes on the sign and instantly watched videos on how the students answered their own questions. I was curious about the amazing teacher that must be behind this project so I did some research of my own and found her at Waikiki Elementary School.

Students in Courtney Carpenter’s classroom are encouraged to ask the most unanswerable, impossible questions they can think of. Then, as teacher, Courtney feels that it is her job not to give them too much help. She says, “It is easy as an adult to work through the problem to come up with a process to solve the problem. But by working really hard to encourage the kids to take small steps to solve questions, they will eventually find a path to solve it themselves.” She adds, “If a child can figure out how long it takes to walk across the room they can figure out how long it takes to walk to the moon.”

Courtney’s belief in asking questions and looking for answers is what allows her students to conduct valuable research. “What do you know or what do you think you need to do?” their teacher repeatedly asks them. She brings out manipulatives—small objects designed as teaching tools to encourage students in the hands-on learning of mathematics. She uses these objects to demonstrate basic math concepts like multiplication and division. Courtney teaches to empower her students.

Students conduct their research on the Internet and model with items from the class. If they are trying to figure out how many cockroaches can fill up the classroom, they research the size of cockroaches on the Internet or they catch one to measure it.

Students usually work in groups. Many of the student-generated questions require measuring something—the size of the classroom, the time it takes to eat something, the circumference of a baseball. They conduct this work as a team. Students then work through their process until they get a reasonable answer—one small step at a time.

“We always discuss what is reasonable,” says Courtney. “I work with students to verify the math. I don’t have a background in math and often the questions feel overwhelming because I don’t know the answer, but if I let go of the anxiety of not being in control, the students and I will go through the steps and eventually feel confident that we reached the correct answer.”

Australian author Mem Fox says, “We need to go above and beyond ourselves to bring an authentic audience to our students.” That applies to writing but also to science. Courtney has gone above and beyond to bring a real audience to her students, and a real purpose to their research. The answers to her students’ questions are now posted on a sign at Diamond Head.

Courtney found a QR code generator online. A QR code is a picture that, when scanned, takes the viewer to a website. It allows you to add video to a static sign or pamphlet. She houses the videos on YouTube and the QR code takes the viewer directly to the YouTube video produced by the students. The students in Waikiki used a basic camera that shoots video.

Then they edited their videos via iMovie. The clips they used of Diamond Head are imported slides that run like a video—all done in iMovie. The sign itself was produced by the Park Department and now encourages tourists to look around, to learn, and to ask questions. What a fantastic way to wrap up creative thinking, research, math, writing, and technology into one teaching package!

Courtney’s students have also produced a pamphlet for the Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources about the Waikiki Marine Life Conservation District. It also utilizes QR codes as a way to embed video presentations. Currently, Courtney’s budding scientists are partnering with the Waikiki Aquarium to produce a video tour that locals and foreign visitors alike can access through QR codes on the exhibits. Courtney is developing partnerships with organizations in her community to expand the walls of the classrooms which gives her students a more authentic educational experience.

In your community, you can find similar organizations or sites that can benefit from virtual tours and added information produced by local students. You can offer your students practical purposes for their research by working together with others in your community: local parks or hiking trails, a zoo, aquarium or museum, historic sites, natural features that attract visitors, a downtown walk.

What can be more fun than researching real things in your own environment for a real purpose?

I visited the National Historic Site of Pearl Harbour where, on December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter planes attacked unsuspecting American Naval vessels, planes, military personnel, and civilians. This became the moment when America became part of World War II. The war ended in the Pacific region on August 6, 1945, when American forces dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

Sadako Sasaki was two-years-old when this catastrophic event happened. Years later she was diagnosed with leukemia, a cancer caused by exposure to nuclear radiation. Sadako clung to the Japanese legend that if you fold 1,000 paper cranes, the gods will grant your wishes. She folded many of her cranes using paper medicine wrappers while she was in hospital. After she died in 1955, Sadako’s paper cranes became a symbol for peace. Eventually, students in the US and Japan began sending each other paper cranes with peace messages written on them. One of Sadako’s original cranes is displayed at Pearl Harbour.

Sadako’s initiative has led to many books, a movie, and tens of thousands of children around the world folding paper cranes as a symbol of peace. I bought a paper crane at the visitors’ centre at Pearl Harbour and found out that all cranes, sold for $1, help the Pacific Historic Parks organization to support educational programs. These include Make A Wish projects for children and their families to visit Pearl Harbour. They also provide a virtual tour of the Pearl Harbour National Memorial for school groups across the nation and internationally who would otherwise not be able to travel to Hawaii.

Your students, too, can join this movement. Children can mail their paper cranes to Ms. Edean Saito, Pacific Historic Parks, 94-1187 Ka Uka Blvd., Waipahu, HI 96797, USA. (email: esaito@pacifichistoricparks.org) You can also send Senbazuru, a garland of 1,000 paper cranes.

For instructions on folding paper cranes, go to: https://www.origami-fun.com/origami-crane.html

Margriet Ruurs

Margriet Ruurs is the author of many books for children, including the picturebook biography The Boy Who Painted Nature, The Life of Robert Bateman, Orca Book Publishers. margrietruurs.com

This article is featured in Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2021 issue.