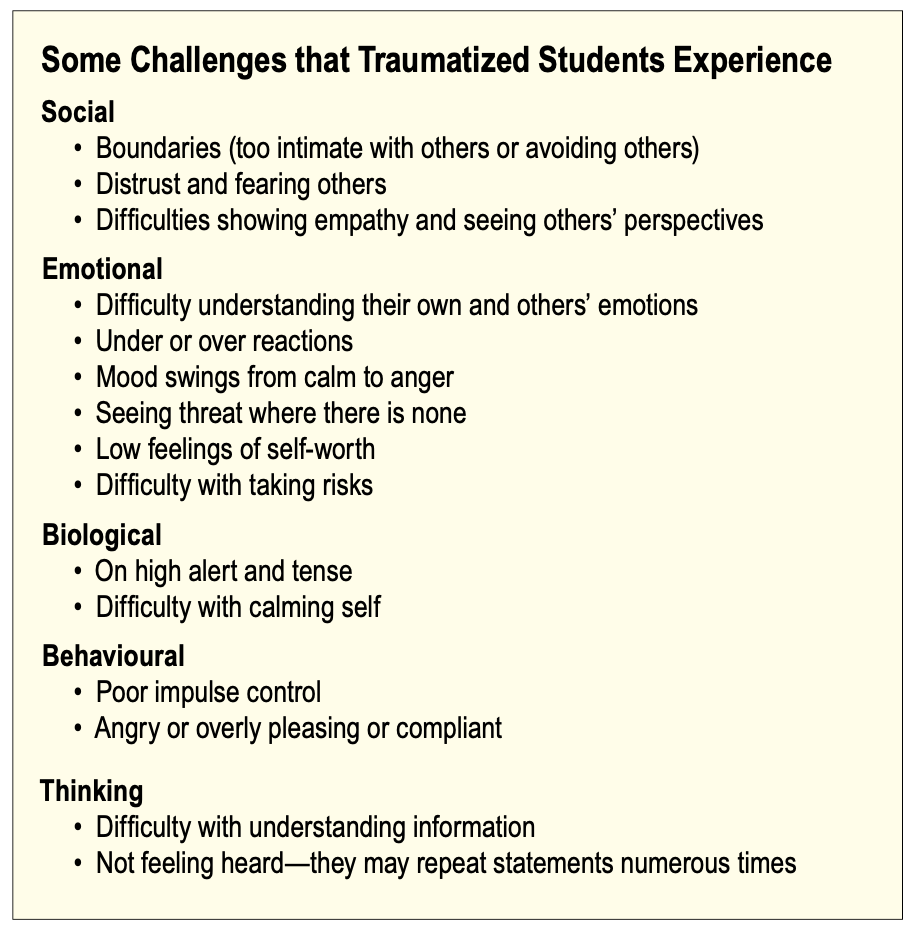

Gabor Mate (2013) states that: “trauma results when things happen that shouldn’t and things don’t happen that should.” Students with trauma live in their emotional brains more so than in their thinking brains. They can be “triggered” in response to people or situations more quickly than others who may see a situation as neutral. An overactive emotional brain from trauma can lead students to see danger where there is none and notice subtle changes in voice tone or facial expression.

Students with early childhood trauma have had to look to only themselves to survive. They may not have had an adult, or attachment figure, who was dependable and trustworthy when they felt scared or in need of food, love, etc. This base of security and safety is significant for future social relationships in terms of feeling for others, intimacy, and the ability to overcome obstacles. Accordingly, the main emphasis for the teacher is to provide emotional support to these students because if they do not calm down their emotional brain they cannot engage their thinking brain in academics. Information must go through the emotional brain (amygdala) before it gets to the thinking brain (prefrontal cortex). Trauma-aware is not a program but a philosophy. It means to support students by providing a caring, calming, and safe environment so that they can move into their thinking brains and grow and develop. It understands the effects of violence and trauma on students.

Relationships are tricky for traumatized students. One day they may want to be close, and another they may push you away. They may inappropriately want affection or completely withdraw and be frightened by offers of support or friendship. Given that clear boundaries may be difficult for them, it is even more important that our boundaries are firm and professional.

Our most important tool for helping others is our relationships with them—relationships that are positive and healthy and compassionate. Traumatized students will learn how to behave by watching how teachers solve problems and communicate with others—by not reacting or directing students while they are emotional, but rather by being responsive, staying calm, listening, being reassuring, and not getting into power struggles.

Our most important tool for helping others is our relationships with them—relationships that are positive and healthy and compassionate. Traumatized students will learn how to behave by watching how teachers solve problems and communicate with others—by not reacting or directing students while they are emotional, but rather by being responsive, staying calm, listening, being reassuring, and not getting into power struggles.

In a helping relationship there is an interest in understanding the student. There is no blame, no focusing on consequences and no forcing behaviours,

but rather a guiding towards new ways of acting. We can provide choices so that individuals can gain some control and power, and provide opportunities for success and for feeling valued.

Important Strategies to Utilize with Traumatized Students

• Provide a safe environment. Students must know that you will not hurt them. Trust must be built over time. It is critical that you will do what you say you will do. Be reliable and consistent and own your mistakes. Also, these students must know that “we’re” in this together. Relationship is key. While you may not get a lot of responsiveness immediately, keep saying “hello”—keep reaching out as this conveys that you are interested and that you care.

• Provide a predictable environment. Develop routines and give warnings of any changes and explicitly explain what will happen step-by-step.

• Anything novel is risky and uncomfortable. If it is new or different, no matter how simple, explain it and give permission.

• Push and pull—they will test us to see if, even when they try to hurt us, we will return. They may like you one minute then hurt you the next. That is the only way they know how to cope in the world. We must recognize that this is not about us, and don’t take it personally; you can’t let them know that you are hurt, but keep reaching out to them.

• Determine effective self-regulation and soothing strategies. Through observation deduce what behaviours the student displays when s/he becomes agitated such as tapping of a foot or a voice change. Determine what the stressors or triggers are—a challenging task, a sensory trigger (e.g., lights, sounds), biological (e.g., lack of sleep, food or water)—and decide with the child what are effective strategies (e.g., drink of water, rocking on a chair, a walk outside, an effective deep belly exercise that has been practised—there are a number on the Internet.) Teach the entire school staff about the triggers and effective responses, as these students will be known by everyone and must be shared and cared for by everyone.

• Establish and practise an exit strategy (a cueing system that will be used by the teacher and student to indicate when the student needs to leave) and have a place for them to go to calm down.

• Prevention is the key—every strategy must be practised and practised because when there is a full escalation there is little that can be done. They are in emotional brain so using language is useless because their left brain, or verbal brain, is not available. Attempting to engage in what they need to be doing or warning of consequences is ineffective. There is one exception to the no-language rule and that is to choose a brief, restorative, and caring phrase and just repeat it, such as, I am here, we are safe (avoid you). Just listen and remain with the student as they do want to be part of the group; they just don’t know how. At this stage, you will have removed the rest of the class.

• Repeat information and check for understanding.

• Teach that there are gradients in emotions, e.g., not every mood is angry, but rather there is annoyed and frustrated as well. Teach corresponding facial expressions (eyebrows and mouth are clues). Teach that bad moods pass. Consult Zones of Regulation program.

• Teach perspective-taking through socialthinking.com materials.

• Use visuals or cueing systems rather than your voice. Go to lessonpics.com or other Internet resources.

Above all, be there for these students.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stace Burnard

Stace Burnard, MA, MBA, B.Ed, R.C.C., has worked in the field of education for over 25 years. She is currently completing a book on teacher wellness. With a background in clinical psychology, she has held positions as educational psychologist, and social-emotional learning and special education consultant. She has advocated for vulnerable children and minority rights as well as led social-emotional initiatives including self-regulation and mindfulness in Yukon and Northwest Territories. Published articles appear in Insights Magazine (BCACC), AdminInfo (BC Principals’ & Vice-Principals’ Association) and a number of British Columbia Teacher Federation (BCTF) magazines. She published Putting the Pieces Together: Building a Curriculum of Caring in 2008 and has presented at First Nations Education Steering Committee conferences, BCTF conferences and the CCBD International conference in the United States. For further information on trauma, self-regulation, and teacher wellness, contact Stace at cloudberrystace@gmail.com and cloudberrywellness.com where you can also find resources and information about presentations for teacher, school, and family wellness.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Winter 2021 issue.