September rode in on confederate coattails, trailing the 150th anniversary of a colonized Canada. In preparation for the new school year, I spent long hours contemplating what our country’s past meant for our future. What might the next 150 years look like, on the current trajectory?

Most of us are all too familiar with the colonial history of North America, the quest for spices and trading posts which evolved into a full-blown conquest for power. We spend arguably less time, however, thinking about the way resources, land and culture are still battlegrounds on our continent today. The economic, political and cultural oppression of First Nations people belongs not only to our history, but to the present moment, and—at this rate—will plague Canada’s tricentennial as well.

So, what does course-correction look like? Who is responsible for decolonizing the hearts and minds of North American citizens, and what does that process entail?

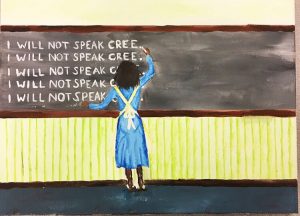

Painting by grade 8 student, Anna Sanders

As the doors opened to welcome a new fall term, I took this question to the most powerful forces for change I knew: the fully loaded poets* of my junior high classroom. When I first introduced the topic of Indigenous Issues to frame our poetry unit, I met crickets—a few chairs squeaked, and a couple of muted groans escaped the back row.

Surprised, I engaged the class in a discussion about their reaction, and their resistance to the subject matter began to take shape. A thick layer of disappointment settled in my gut as I realized our stiff-armed, dried-up, and completely dispassionate approach to teaching about Native American peoples had landed flat with this crew, for many grades prior. The educational system I was part of had stripped Indigenous Knowledge of its foundational emphasis on experiential learning and passed out textbooks recounting a timeline of battles and legislation. These textbooks were accented by black-and-white photographs of residential school survivors and included lesson plans outlining a no-waste approach to buffalo. We had mauled Indigenous culture, shaping it into a flaccid caricature of the vibrant resiliency I witnessed on reserves and heard echoed in the voices of Indigenous scholars.

No wonder the students groaned; it would have been wrong not to. I paused long enough to add my own lamentations to the mix. And then, we got to work.

Centring around the theme of rootedness, our inquiry tied the study of Native American people to an investigation of our own cultural heritage. We titled our poetry exploration Rooted: Grounding in a World all Dug-Up, and discussed what it meant to be rooted in culture, community, place, tradition, language, worldview, family, God and self. The classroom transformed into a place of courageous creativity as students engaged with life-sized identity questions, including what does rootedness mean, why does it matter, and what do roots have to do with identity?

We looked at origin stories, stereotypes, appropriation, the democracy of species, lost languages, seven fires, immigration, and relationship to the land. Students talked about the project in the hallways and at dinner with their parents, who commented curiously about how engaged their children were. We queried Indigenous notions of sexuality, creativity, humour, medicine, leadership, and identity. Finally, we used the discussion to create an art piece, and translated our grappling into spoken word poetry.

The performances had some attendees in tears, some offended (work is often powerful when it offends), and all enraptured. Parents who planned to leave after their child presented, stayed in awe. Kids described the event as emotional, profound, and in the words of one student, the poetry “filled the empty space of the room with admiration.”

If Indigenous issues are the curriculum’s new buzzwords, we have a responsibility as teachers to guide this engagement away from appropriation and into a space of collaboration and authentic engagement. The First Peoples of Canada made a home here long before colonizers poked a flag into the ground, and their culture holds a deep knowing; a wisdom frayed at the edges from being shared so many times. A knowledge breathed into stories and woven into relationships, passed down from elder to elder to elder. A way of existing in relationship that balanced giving and taking.

Today, much of the land we call Canada and the United States is treaty territory, which means we all have a responsibility as people who live here. We are treaty people, because we are in relationship with each other and the land. And under our watch, fish are floating belly up in poisoned rivers, acid rain from chemical plants scorches the earth, and First Peoples too, are suffering. Their warrior spirits are beating back addiction and abuse, and rubbing salve on the open wounds of suicide and poverty.

This year’s poetry café seeped into the bones of the students who participated, and left all who witnessed it changed. In an attempt to answer my original question: I think figuring out how we got here as a nation is an integral part of deciding where to go next. Studying this history with new eyes will create room for new possibilities and new stories: stories of collaboration, justice and healing. In the words of Gary Nabhan, we can’t move forward with restoration, without re-story-ation. In other words, our relationship with the land cannot heal until we hear its stories—and the stories of its people. And so it is by seeking out these voices, and learning how to find our own, that we begin to honour what was lost. Only then, might we have a hope of moving forward.

*Note The term “fully loaded poet” is a line from the song It Is Written by the band Nahko and Medicine for the People.

Lesley Machon

Lesley Machon is a junior high language arts teacher from Calgary, Alberta. As a globetrotter who has taught, learned, and volunteered abroad, she continually cultivates a passion for social justice advocacy in her work. She involves herself in many projects committed to fostering greater inclusivity and deeper understanding, both cross-culturally and trans-culturally, and finds herself at home in the many intersections between people and place.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Spring 2018 Issue.