It is said that reading, in itself, is a revolutionary act.

Literacy is an important issue in Canada and throughout the world. An amazing example of how one country dealt with the issue of mass illiteracy with astounding success can be seen in Castro’s Cuba in the 1960s. Being that Cuba is included on many curricula for grade 11 social studies and grade 12 history classes, an account of how Cuba undertook a mass literacy campaign in 1961 may appeal to students and teachers alike.

Literacy is an important issue in Canada and throughout the world. An amazing example of how one country dealt with the issue of mass illiteracy with astounding success can be seen in Castro’s Cuba in the 1960s. Being that Cuba is included on many curricula for grade 11 social studies and grade 12 history classes, an account of how Cuba undertook a mass literacy campaign in 1961 may appeal to students and teachers alike.

The opportunity to acquire the ability to read, write and calculate is recognized as a basic human right, one that enables the acquisition of the skills necessary for effective and productive performance within society. Many people think that illiteracy has been eradicated, like smallpox, yet “International Perspective,” a recent paper published by UNESCO Institute for Statistics, states that around one billion people world-wide cannot read or write—26% of the adult population. In developing countries, it is estimated that one person in four is illiterate, and UNESCO states this figure is probably a significant underestimate. Insofar as literacy has been proven to be key to peace, health and the economic success of people and nations, this state of educational impoverishment is dramatically disabling.

In 1959, when the Revolutionary government took power in Cuba, one quarter of the population was totally illiterate, one million of whom were adults. Fidel Castro realized immediately that the government had to enable the “acquisition of the skills necessary for effective and productive performance within society” if the country was to move forward. How Cuba tackled this challenge is one of the most inspiring mass education campaigns in history and a fascinating story that many so-called developed nations and disaffected youth the world over can learn from.

Speaking before the General Assembly of the United Nations on September 26, 1960, Fidel Castro made an audacious announcement. By the end of 1961, he said, Cuba would be “un territorio libre de analfabetismo”—a land free from illiteracy. With few resources, the campaign got underway in May of 1961, delayed by the Bay of Pigs invasion in April.

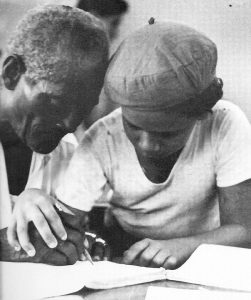

Perhaps the most amazing aspect of the campaign is that the majority of the teaching was accomplished by 100,000 teenagers—average age 15—who responded to the national call for youth volunteers. Called “brigadistas”—members of the brigade—those young people left the comfort of their homes to go and live with illiterate learners wherever and however they lived. Each brigadista was given two sets of army-style uniforms, an olive-green beret, a pair of army-style boots, two pairs of socks, a warm blanket, a jute hammock and a kerosene lantern imported from China so they could teach where light wasn’t available. The teaching resources the brigadistas carried to their assignments were flimsy: a teacher’s manual and lesson guide and work books for the learners. What the brigadistas lacked in resources, they made up for with vigour, nationalistic zeal to do something important for their country and the determination to make Fidel Castro’s words reality—that is, to make Cuba a literate country.

Perhaps the most amazing aspect of the campaign is that the majority of the teaching was accomplished by 100,000 teenagers—average age 15—who responded to the national call for youth volunteers. Called “brigadistas”—members of the brigade—those young people left the comfort of their homes to go and live with illiterate learners wherever and however they lived. Each brigadista was given two sets of army-style uniforms, an olive-green beret, a pair of army-style boots, two pairs of socks, a warm blanket, a jute hammock and a kerosene lantern imported from China so they could teach where light wasn’t available. The teaching resources the brigadistas carried to their assignments were flimsy: a teacher’s manual and lesson guide and work books for the learners. What the brigadistas lacked in resources, they made up for with vigour, nationalistic zeal to do something important for their country and the determination to make Fidel Castro’s words reality—that is, to make Cuba a literate country.

Toward the end of that summer of 1961, campaign organizers saw that they would have to get more human resources into the campaign if it was to succeed. Workers of all kinds were released from their jobs to spread throughout the country to teach. Urban dwellers were asked to volunteer to teach in their neighbourhoods. Re-opening of regular schools was postponed until January 1962, enabling professional teachers to volunteer as tutors wherever needed. The motto became: For each one who needs to learn, there is someone to teach. The country became one gigantic school. When the campaign ended a scant seven months after onset, illiteracy had been reduced from 25% to 3.9%. On December 22, 1961, Cuba raised a flag that declared Cuba: Territorio Libre de Analfabetismo. 707,000 adult Cubans, mostly campesinos, agricultural labourers, had learned to read and write. The eldest was a 104-year-old woman who had been born a slave.

While an individual may have basic reading, writing and numerical skills, they may not be able to apply them to accomplish some tasks that are necessary to make informed choices and participate fully in everyday life. Such tasks may include:

- reading a medicine label

- reading a nutritional label on a food product

- balancing a chequebook

- filling out a job application

- reading and responding to correspondence in the workplace

- filling out a home loan application

- reading a bank statement

- comparing the cost of two items to work out which one offers the best value

- working out the correct change at a supermarket.

To further enable its newly-literate population, a program of continuing education was put in place in Cuba immediately following the end of the campaign. When the writer of this article was in Cuba (1964 – 1969) she observed this continuing education program taking place in workplaces, cafeterias, vestibules of apartment buildings—everywhere in fact, even in open air situations.

The present high rate of literacy in Cuba is one of the proudest accomplishments of the Cuban Revolution. Given the high incidence of world illiteracy, it is important to revisit the achievement of Cuba’s literacy campaign to understand how it changed Cuba’s history. The result of Cuba’s literacy revolution was nothing less than a transformation, not only of each newly-literate individual but of the nation itself. What Cuba began in 1961—guaranteed universal education—continues today. According to UNESCO, currently, one of every fifteen Cubans holds a university degree. UNESCO has stated that the Cuban struggle to eradicate illiteracy and bring all students and adults to an effective functional level has proven itself not just a one-time tour de force, but rather a success story that has no end.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shirley Langer

Shirley Langer

Shirley Langer lived and worked in Cuba for almost five years in the mid 1960s. She is the author of the recently published book, Anita’s Revolution, historical fiction chronicling the Cuban literacy campaign of 1961. The theme of the novel is twofold: the power of education to effect social change, and a tribute to the potential of young people to make significant contributions to society when given the opportunity. The novel is available as an e-book from major online bookstores. The book in print form may be purchased online from createspace, ordered from Red Tuque Books, or by contacting Shirley directly by email: shirleylanger@gmail.com. To learn more about Anita’s Revolution, visit the website: anitasrevolution.com. Presentations on Anita’s Revolution and its themes in schools may be arranged. Shirley currently volunteers at Literacy Victoria.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s Sept/Oct 2013 issue.