Every teacher attempts to create an environment that is optimal for learning, yet finding useful strategies for positive classroom management is a constant challenge. This challenge becomes magnified for teachers working with students who are struggling academically, behaviourally or culturally. The integration of these students with those achieving at average levels, through a focus on common strengths, can serve to bridge the divide and create an inclusive climate.

Our team of researchers and practitioners at the Centre of Excellence for Children & Adolescents with Special Needs at Lakehead University suggest that teachers examine their students’ strengths and incorporate them into day-to-day activities. We all know that every student has at least one strength to offer the class. Once those strengths are identified and encouraged, it creates a kind of positive ripple effect within a classroom—a type of “pay-it-forward” scenario where all students “pay-their-strength- forward” without much effort. Researchers believe this will happen naturally once students understand that they are valued because they have something of importance to contribute. The idea is to encourage students to use their strengths as a tool to deal with issues they may be encountering at school, rather than to focus on shortcomings.

Principals and teachers in northwestern Ontario are teaming up with academic researchers to offer practical classroom strategies that help educators apply student strengths to both classroom management and to everyday lessons using activity-based ideas. These easy-to-use concepts are intended to spark ongoing ideas and dialogue among teachers about other ways that strengths could be incorporated into the classroom.

Understanding Student Strengths

Recognizing student strengths allows the teacher to gain a well-balanced understanding of a child’s behaviour and learning style in order to set reasonable expectations. By building a student strength profile for each student, the teacher will have a tangible resource for communicating with that student, parents and other school staff. Identifying strengths can be done in a number of ways depending on the teacher’s end goals. In our work at Lakehead University, we have developed a Strengths Assessment Inventory (SAI) tool that can be easily completed online or on paper by students, like any self-assessment. The SAI helps students identify their positive qualities, competencies and characteristics that are valued by society. These positive attributes can also be used to track student’s understanding of “self.”

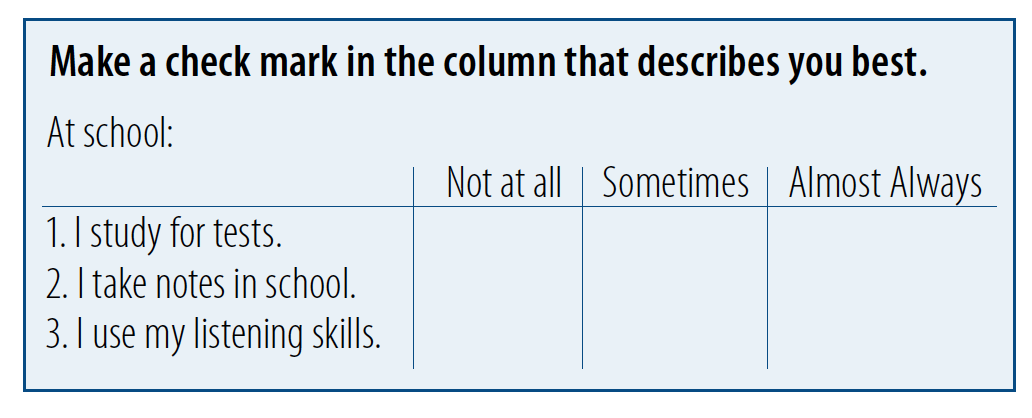

The SAI tool is a behavioural checklist that students in grades 4 to 8 individually complete in a classroom, computer lab or library.1 It is based on student strengths that are related to seven domains of functioning in the student’s life, including: strengths at school, strengths during my leisure time, strengths with friends, strengths from knowing myself, strengths from being involved in community activities, strengths from my faith and culture, strengths from my goals and dreams. For instance, in the “strengths at school” domain, students are asked to identify a number of their competencies, such as (their ability to): listen, complete work, get along with staff, or study for tests.

The SAI tool is a behavioural checklist that students in grades 4 to 8 individually complete in a classroom, computer lab or library.1 It is based on student strengths that are related to seven domains of functioning in the student’s life, including: strengths at school, strengths during my leisure time, strengths with friends, strengths from knowing myself, strengths from being involved in community activities, strengths from my faith and culture, strengths from my goals and dreams. For instance, in the “strengths at school” domain, students are asked to identify a number of their competencies, such as (their ability to): listen, complete work, get along with staff, or study for tests.

Strategies To Include Students Who May Be Struggling In The Classroom

Even though some students struggle, they all have inherent strengths. It is a natural inclination for any teacher to want to identify concerns and attempt to remedy them. Teachers can then encourage students to use their strengths to deal with their struggles. We have defined strength as “a set of personal competencies and characteristics of the child or adolescent that were developed and embedded in culture and valued both by the individual and society.”2 Strengths can develop from everyday life experiences of students. For example, if a struggling student identified playing soccer as one of their strengths, the teacher could encourage the student to view the classroom as a soccer field and the teacher as their coach. They could be encouraged to show “good sportsmanship” in the classroom and “show respect for the other team” when dealing with other kids who are bothering them. Identifying positive character traits in students gives the teacher the ability to encourage the student to use his/her natural propensities to help them make healthy decisions throughout the school year3.

Use Strengths To Shape, Organize, Manage and Plan Your Classroom

Knowing student strengths also gives teachers a more balanced understanding of each student. Teachers can compile the information and use it for practical planning purposes—from deciding how to arrange students into compatible groups, to structuring lesson plans that will motivate all students regardless of their particular difficulties. Strengths can be used to “hook” the class by appealing to their interests and capturing their attention, thus motivating them to learn. Tailoring the classroom environment and planning with strengths in mind will help students not only reach their potential, but also help students gain a more balanced sense of self and others4.

Applying Student Strengths To Group Activities In The Classroom

Strengths can be used to help teachers set up and manage group work or implement group-based programs such as Tribes5 or literature circle groups. Practical strategies can be put in place to assist students and encourage them to improve. For instance, a teacher might consider teaming up the self-identified “non-listeners” with those who are proficient listeners and can help keep the others on track. In one class in which strength is used as a strategy to engage the learners, it has worked very well to begin math lessons by summarizing the strengths of each of the students. The teacher then proceeds to buddy up students according to areas of need and areas of strength in the math curriculum. Students in this class are also seated in groupings according to strengths and needs so that each of the students has the opportunity to model and observe.

Sometimes there are differences between what the students believe are their strengths and what the teacher sees. For instance, some children (particularly younger ones) may identify themselves as being good listeners, but the teacher may not feel this is the case. Also, some students may not be willing to identify themselves as a “non-listener.” When these students identify their strengths, it is valuable for teachers to explore any discrepancies. Discrepancies can be used as a teachable opportunity, for example, discuss what it looks like and what it means to be a good listener.

How To Design A Strength-Based Classroom Environment

Try keeping a log book of strength observations. When students demonstrate their strengths they should be recorded. This tool can be useful for bestowing rewards or when assigning classroom helper jobs or providing points of discussion at parent-teacher meetings. Strengths inventories and observations can also be used as a source of information for preparing Individual Education Plans (IEPs), for interdisciplinary teams, educational assistants, and to inform report cards.

Another benefit to keeping an inventory of strengths on file is that it will send a signal to students that positive self-awareness is one of the key goals toward building successful character at school. Strengths can then be recorded and used as an incentive to continue to engage individuals over longer periods of time. For example, strengths files could be passed along from teacher to teacher as the students transition into higher grades.

A Strength-Based Classroom Will Encourage Students To Become Consistent Learners

Positive, strength-based learning environments do not function just to boost self-esteem. Acknowledging students’ strengths engages the students on a consistent basis and encourages them to learn. A strategy that has been found to be effective, particularly with high-risk children and adolescents, is to post student strengths in a visual place where they can be viewed each day. Creating a wall of strengths on a bulletin board, including summarized student profiles on a simple sheet of paper with the student’s name, picture and/or self-portrait is one suggestion. Another is to simply ask a student to list his/her top three strengths to be displayed in the first week of school which will not only raise self-esteem, but will offer a perspective to the whole class and to all teaching staff. The wall can be used for two purposes, as identification tool for the entire school community and a visual point of strength for the entire class.

In one class in which a strengths wall was put up at the beginning of the school year, the students have continually added strengths that they have recognized about their peers. One example of how well this works towards building a student’s self-worth is Sarah. Sarah’s grandpa approached her teacher one day, sharing that Sarah wasn’t feeling very well. He had offered to let her stay home, but Sarah had said no because the class had reading buddies that day, and she didn’t want to let her buddy down. Sarah’s grandpa said that he had never seen her so enthusiastic about school, and that normally she would jump at the chance to stay home. He continued to say that when her strength went up on the wall that she came right home and told him about it and was really proud. The additional strength that was put up on the wall was, “Sarah is fantastic with little kids.” Since that particular strength went up, Sarah has been volunteering in the JK/SK room and loving it.

The creation of wall of strengths is suggested as the first step; however, there are a number of other activities that can also be used. Consider starting a strengths-based theme in a student writing journal or portfolio to help students document their feelings and ideas related to self-concept, personal strengths and self-expression. Also be sure to offer ongoing opportunities for students to write about their progress as time goes on (perhaps on a weekly or monthly basis).

Depending on the student’s age, journal and portfolio activities using strengths can be adapted to incorporate balanced literacy strategies. For example, read an excerpt of text related to strength, then have students write their reaction to it. Or the teacher could offer a writing theme related to strengths. For example, a writing theme might be “What makes you special in relation to your strengths?” or “Where could you use your strengths in or outside of the classroom?”

Having students keep journals based on self-expression is an excellent way to monitor progress, assisting educators with the difficult task of communicating and reporting on student behaviour with parents, school administrators, educational assistants or early intervention specialists. Implementing strengths-based rules and routines is another option for a strength-based classroom. Maintaining a reasonable level of harmony in the classroom is in everyone’s best interest considering the average class spends over 900 hours together over the course of a school year. Focusing on student strengths is a positive way to respond to misbehaviour and it is important to state what IS working rather than what isn’t. For example, in one class, a student who had spent time in a behavioural class setting was experiencing some challenges adjusting to a regular classroom setting. Posting her strengths on the classroom wall, and verbally referring to them often when there are instances of misbehaviour, has given her a new opportunity to shine. She began re-inventing her image, and striving to live up to the positive statements that she heard about herself.

Another activity geared toward building an environment of mutual respect and security is a strength sharing circle. Sharing circles are commonplace classroom activities; they are sometimes called “circle news” or “sharing time” activities. The purpose of sharing activities is to open up the floor to communication and oral expression and enhance students’ intrapersonal skills. A strengths sharing circle goes beyond those basic expectations by asking students to become aware of other students’ strengths. A strengths sharing circle allows students to hear others’ perspectives on their strengths, opening the door to self-awareness and understanding which might otherwise go unrecognized. It is an excellent way for students to visualize themselves through the lens of others. A September classroom shuffle moved some Grade 5s into an existing Grade 4 classroom. Some anxiety existed for students about moving to a new class and away from their Grade 5 friends. Were they moving to the “dumb class”? To address these feelings, the class sat in a sharing circle and examined the strengths wall. The students pointed out the great things that they were learning about their new classmates and themselves. “I didn’t know that Karey is a great hockey player!” “Desiree does help others all the time and is really generous! She plays with the JKs every recess!” By the end of the sharing time, the students felt really good about themselves and their classmates. They couldn’t believe all of the wonderful things that they were realizing about their friends, and their faces glowed when a classmate commented on their strengths. They continue to point things out to each other on the wall: “Isaiah is funny…we should tell him this joke!”

Strength-Based Rules and Routines

Creating a positive classroom environment is highly dependent on the teacher who can model appropriate strength-based verbal cues and routines in the classroom. Precise cues help students get back on track quickly and efficiently. Be specific when praising a student, “You listened closely today. I am proud of you.” Use “I” statements when pointing out a student’s specific strengths. For example, “I know that one of your strengths is being organized, so why does your binder look disorganized today? That is not like you.” When a student has done well on a particular assignment, it is important to recognize this in front of other students and/or staff members, “You did very well on this assignment, I am very impressed. You are very good at adding two digit numbers. I will be phoning your parents to let them know how strong you are in this area.”

Although verbal cues are effective, enforcing strength-based rules goes beyond teacher responses to behaviour. A strengths-based approach to setting rules could be modeled using a mutual strengths contract. The mutual contract is a designed list of rules that is agreed upon in cooperation with the class. Have students sign the strengths contract, whereby agreeing to follow the rules that they have helped in developing and agreed upon. Ensure that the rules are directly related to their strengths. For instance, one rule might read: “One of our strengths as a class is our ability to communicate appropriately— if we become too noisy we agree that our teacher will signal us to communicate quietly.” Positive verbal and physical cues will help prompt the class and get them back on track and achieve balance between discipline and positive reinforcement.

What You Stand To Gain

Ideally your students will learn to recognize each student’s strengths and work together as a holistic community. By encouraging students to use their strengths to deal with difficulties, they will have the confidence to tackle challenges using strength-based solutions. Teachers must guide students in this process and take the opportunity to incorporate student strengths into the day-to-day curriculum. Helping students recognize their strengths will, in turn, allow teachers to set realistic expectations. These strengths concepts must be consistently developed, reinforced and re-evaluated in an effort to encourage dialogue among teachers and between teachers and parents. By meeting the needs of mainstream students and at the same time engaging those who struggle, students will be able to take responsibility for their learning and develop their own interest and talents from a strengths perspective. Using this kind of approach when interacting with students will help to create a cultural shift in the school that sets the stage for growth and development.

Notes

1 Please note, elementary school children in grades 4 – 8 are highlighted based on prior pilot programs, research and experiences with the SAI tool which were conducted in schools during the 2007-08 school year. Researchers involved in the study explain that students younger than grade 3 can use the tool; however they need much more assistance to complete it.

2 Rawana, E.P., Brownlee, K., & Hewitt, J. (2006). Strength Assessment Inventory for Children and Adolescents: Parents, Teachers, and mental Health Staff Form. Thunder Bay, ON: Department of Psychology, Lakehead University.

3 Greenberg, M.T, Weissberg, R.P., O’Brien, M.U., Zins, J.E., Fredericks, L., Resnick, H., & Elias, M.J. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58, 466-474.

4 Skaalvik, E.M., & Hagtvet, K.W. (1990). Academic achievement and self-concept: An analysis of causal predominance in developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 292-307.

5 Tribes Learning Communities www.tribes.com

Thousands of schools throughout the United States, Canada, Australia and other countries incorporated the Tribes program into the classroom. After years of “fix-it” programs to reduce student violence, conflict, drug and alcohol use, absenteeism, poor achievement, etc., educators and parents now agree, creating a positive school or classroom environment is the most effective way to improve behaviour and learning.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Edward Rawana

Dr. Edward Rawana is a practising child psychologist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Lakehead University. He is also Director of the Lakehead Site of the Centre of Excellence for Children & Adolescents with Special Needs (CECASN). He is leading the research on strength in children, which is being studied in relation to education, social services and mental health services for children.

Kim Latimer

Kim Latimer is formerly the national Communications Coordinator for CECASN. She has degrees in both Education and Journalism and is currently employed with CBC Radio in Thunder Bay.

Jessica Whitley

Dr. Jessica Whitley is Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa. She has worked extensively with students with various exceptionalities and conducts research in the area of psychosocial outcomes for students at-risk.

Michelle Probizanski

Michelle Probizanski is a principal with the Lakehead District School Board in Thunder Bay, Ontario. She works tirelessly to promote a strength-based approach when meeting the needs of the students in her school.

This article is from Canadian Teacher Magazine’s November 2009 issue.